Introduction:

Mental health literacy is a modifiable factor that has been shown to influence mental health outcomes[1-4]. Understanding factors and how they interact with population socio-demographic characteristics is highly necessary in the design of targeted and effective schemes for mental health promotion, particularly in adolescent populations. However, there is very little evidence informing this field from populations in low-and-middle income countries, including Ethiopia. There is public interest in understanding what actions to take to promote health and prevent diseases[5]. Health promotion approaches need to consider the capacity, ability, and motivation of their target audience to access, process, understand, and use health information and health services. These factors define individuals effectiveness to make proper health decisions, and these attributes combine to form what is termed health literacy[6-13]. However, this definition of health literacy does not specifically address mental health[2]. Mental health issues are often neglected and typically receive much less attention than physical health[14]. Consequently, mental health literacy, a term coined by Anthony F. Jorm and colleagues[15], has evolved as a separate school of thought [1,3,4]. Mental health literacy is defined as the extent of an individual's recognition, knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about mental disorders, the risk factors and causes, and the sources of help available[1-4]. It encompasses their ability to recognize specific disorders and types of psychological distress, interconnected with attitudes that facilitate recognition, knowledge and appropriate help-seeking[3,5,15]. It also takes into account the primary constructs of knowledge and beliefs about risk factors and causes of mental health problems, seeking of information related to mental health, and awareness of self-help interventions and professional help available[3,5,15].

From the theoretical viewpoint, the integrated theory of health behavior change (ITHBC) states that "health behavior change can be enhanced by fostering knowledge and beliefs, increasing self-regulation skills and abilities, and enhancing social facilitation" [16]. Adopting this model into the mental health context indicates that similarly, in an integrated theory of mental health behavior change, mental health literacy has proximal and distal mental health-related outcomes[16]. Epidemiological studies have also revealed that awareness of mental health issues and positive attitudes are highly associated with mental health service use, access to mental healthcare, and positive mental health outcomes[9,17,18].

Understanding the role of adolescent mental health literacy in promoting positive mental health has been shown to contribute to wellbeing during adolescence and adulthood[19,20]. It is informative in the design of targeted and effective mental health promotion resources. Adolescence is a critical period of physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development[21-23] and has been identified as being a crucial period for instilling positive mental health behaviors, as these developments shape other health-related behaviors and skills, and abilities[24]. Many conditions associated with mental ill-health occur or develop during adolescence, and many continue until adulthood As such, adolescence is a critical stage in which to influence individuals' focus on mental health literacy and health behavior change. However, empirical evidence shows that little emphasis had been placed on promoting positive mental health to adolescents, or preventing mental disorders, treatment-seeking, or seeking assistance for themselves and others[5]. From the limited amount of evidence about adolescent mental health literacy, it has been shown that only 25% of adolescents with mental health problems get professional help and treatment[25,26]. Further, 10-20% of children and adolescents globally are affected by mental health problems [27-30], which is reportedly higher in Africa, most notably in Sub-Saharan Africa[31], where Ethiopia accounts for the largest population in the region [32-34]. Evidence about adolescents' capacity to recognize mental disorders, help-seeking intention and help-seeking behavior is limited [14]. A small number of organizations in high-income countries such as the USA, Australia, and Canada have launched nationwide adolescent mental health literacy campaigns[35-40]. However, mental health, much less adolescent mental health, has not always been viewed as a public health concern, again most notably in low-and-middle income countries, including Africa. Health literacy in general, and mental health literacy, has rarely been mentioned in Ethiopian public health discourse.

Socio-demographic characteristics play a significant role in health behavior and health outcomes [41-43]. Mental health status, and knowledge and awareness about mental health are likely to be shaped by economic, environmental, and socio-demographic inter-individual differences[44]. For example, significant gender differences in mental health literacy were found among young Australians, with female participants being significantly more capable than their male counterparts at recognizing the symptoms associated with mental illness[45]. Understanding the relationships between socio-demographic characteristics and mental health literacy is imperative for considering how these differences affect the efficacy of materials on mental health promotion targeted at adolescents. However, there is very little quantitative evidence regarding the effects of gender, age, education level, ethnicity/cultural/religious affiliation, and family background on adolescent mental health literacy[46]. Therefore, the present study examined the level of mental health literacy among adolescents from schools in an urban Ethiopia, and its relationship with socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, age, school grade, ethnicity/culture, and maternal and paternal education levels.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and design

The present study was a cross-sectional survey carried out between April and July 2020 in Dire Dawa, a city in Ethiopia known for its ethnic, cultural and language diversity. The study population was adolescents in urban schools in grades 5 to 12, aged 11-19 years.

Sample size and sampling

An estimated minimum sample size (n=565) was obtained assuming a 95% confidence level, 5% significance level (α), a standard deviation of a normal distribution (Z1-α/2 = 1.96), standard deviation of the measure in the population (=18.183), and margin of sampling error (d=1.5) using an equation[50]. Hence,

However, about a sample size of 934 was targeted when taking into account the design effect (d=1.5) and considering a 10% non-responders and dropout rate.

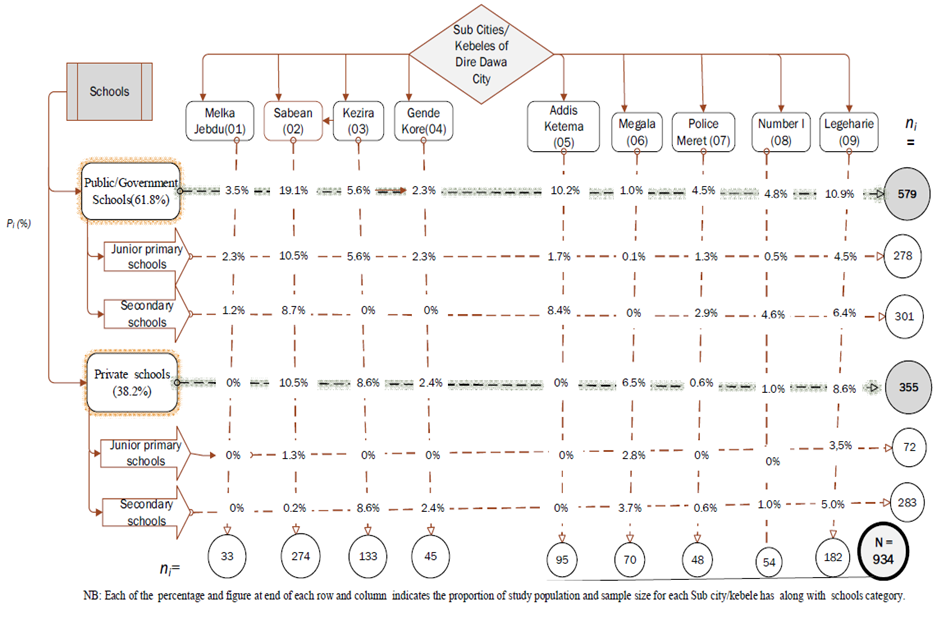

Study participants were selected using combination of multistage (schools, classrooms, then individual students) systematic and random (using list of the students in fixed intervals of their roll numbers) sampling methods. Lists of schools and students were obtained from Dire Dawa Education Bureau. The statistics of the student population of each sub-city was determined, and a sample of public and private schools was selected randomly. Finally, sample participants were randomly selected from each selected school, proportional to the number of students for that schools category and targeted grade level (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: Sampling method for selecting participants from each sub-city and school. |

Data Collection Tools

Mental health literacy was measured using the mental health literacy questionnaire, MHLq [43], a freely available and validated tool used in adolescent populations [1,48-56]. It was further tested for its reliability (Cronbach's alpha=0.834) in the present study setting. The version of the MHLq used in this study comprised 33 items, with each item eliciting a response using a five-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=slightly disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=slightly agree, 5=strongly agree). The MHLq items comprise statements covering recognition, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of adolescents towards mental health issues[1-4].

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23. Statistical significance was considered at a threshold of p<0.05 and 95% confidence intervals were used. Reverse scoring was performed for negatively-keyed items (Q7, Q12, Q15, Q17, Q24, & Q26) of the MHLq before computing each individual's mean score. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the socio-demographic characteristics and the distribution of mental health literacy. The mean, standard deviation, median, mode, range, interquartile range, skewness, and kurtosis of the mental health literacy score were computed.

A one-way ANOVA was used to test the variance in mental health literacy with the socio-demographic characteristics captured[57]. Bivariate and hierarchical multivariate linear regression analysis was performed, adjusting for age, to analyze the association between socio-demographic characteristics and mental health literacy. Each socio-demographic category was transformed into a binary variable with no=0 and yes =1 before use in the predictive regression model.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the KIIT University, KIMS, Institutional Ethics committee (Reference: KIIT/KIMS/IEC/63/2019) and Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences Institutional Health Research Review Ethics Committee (Reference: 00.H.M.S./10.0/3763/2020). Written informed consent was obtained from school principals, from the parents of adolescents aged under 15 years, and from all participants.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

From the 934 potential participants who were approached, 751 (80.41%) students participated in the study, comprising 50.1% male participants and 49.9% female participants. Of those who completed the study, 2.66% of respondents were removed due to having significant missing data. As such, the responses of 731 participants formed the sample, which represented 129.38% of the calculated minimum (n=565) study sample size (Table 2). The mean and standard deviation of participants age was 16.27±2.19) years for male participants and 15.95 ± 2.02 years for female participants. The socio-demographic characteristics of these participants, including their ethnicity/ cultural affiliation, age group, grade level, and parental education (maternal and paternal) are given in Table 1.

| Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants |

| Socio-demographic Characteristics |

Male (n=366) |

Female (n=365 |

P value |

Mean age (SD*) |

16.27(2.19) |

15.95(2.02) |

0.037 |

Ethnicity / Cultural affiliation |

Amhara |

43.0% |

57.0% |

0.000 |

Oromo |

62.8% |

37.2% |

|

Somali |

51.2% |

48.8% |

|

Others |

52.6% |

47.4% |

|

Age group in years |

11-13 |

13.7% |

12.9% |

0.079 |

14-16 |

36.6% |

44.7% |

|

17-19 |

49.7% |

42.5% |

|

School grade level |

Upper elementary Grade 5-8 |

39.3% |

43.0% |

0.571 |

Lower Secondary Grade 9-10 |

39.6% |

40.0% |

|

Upper secondary Grade 11-12 |

21.0% |

17.0% |

|

Maternal education level |

Non-educated |

63.7% |

60.5% |

0.575 |

Elementary Level |

8.5% |

9.3% |

|

Secondary level |

19.9% |

23.6% |

|

College or above |

7.9% |

6.6% |

|

Paternal education level |

Non-educated |

54.6% |

54.2% |

0.128 |

Elementary Level |

5.7% |

2.5% |

|

Secondary level |

24.6% |

28.2% |

|

College or above |

15.0% |

15.1% |

|

Level of mental health literacy

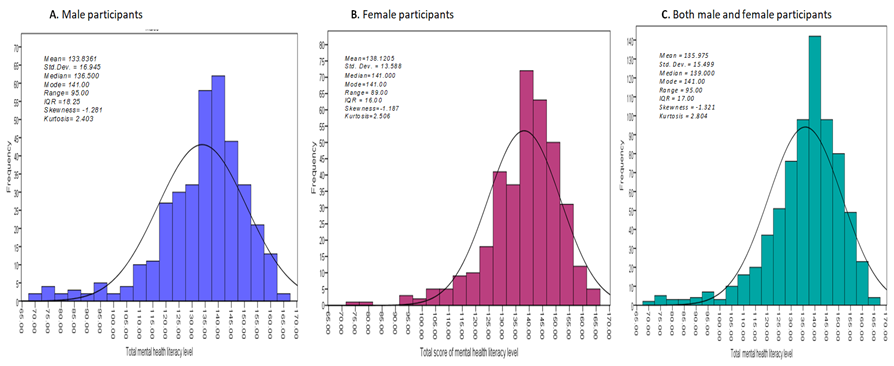

The mental health literacy score could be approximated to a normal distribution, with a skew was nearly 1.32. The mean mental health literacy score was 135.975±15.499 with median and interquartile ranges of 139 and 122-156, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, mental health literacy varied with participant gender, with female participants showing slightly higher mental health literacy (M=138.12, SD=13.588) than male participants (M=133.64, SD=16.945), F(1,729)=6.120, p=0.014.

|

Figure 2: Descriptive analysis of mental health literacy for (a) male (b) female and (c) both male and female participants. |

The association between mental health literacy and socio-demographic factors

The effect of ethnicity/cultural affiliation of mental health literacy score was highly significant for both male and female respondents. It was significantly different between male adolescents across their ethnic/cultural affiliations with score of Amhara (M=135.83, SD=16.93), Oromo (M=133.59, SD=15.71), Somalia (M=124.48, SD=18.03) and other ethnic/cultural affiliations (M=138.90, SD=16.08), (F(3,362)=6.115, p =0.000). Similarly, significant difference was observed between female adolescents with scores in Amhara (M=140.56, SD=12.96), Oromo (M=134.74, SD=15.11), Somalia (M=132.24,SD=12.37) and other ethnic/cultural affiliations (M=135.44, SD=9.71), (F(3,361) =7.243, p =0.000). Maternal education (F(3,361)=2.866, p =0.037) and grade (F(2,362)=4.466, p =0.012) were significantly associated with mental health literacy in female but not male adolescents. There were no significant effects of paternal education for either female (F(3,362) = 0.360, p = 0.782) or male (F(2,363) = 1.811, p = 0.165) participants (Table 2).

| Table 2: The association between mental health literacy and socio-demographic characteristics (One way ANOVA at p<0.05, 95% CI) |

| Socio-demographic characteristics |

Mental health literacy level |

Male adolescents |

Female adolescents |

Mean score(SD) |

95% CI |

p-value |

Mean score(SD) |

95% CI |

p-value |

Total (altogether) |

133.84(16.95) |

132.09-135.58 |

|

138.12(13.59) |

136.72-139.52 |

|

Ethnicity/cultural affiliation |

Amhara |

135.83(16.93) |

133.28-138.37 |

.000

|

140.56(12.96) |

138.87-142.25 |

.000

|

Oromo |

133.59(15.71) |

130.87-136.32 |

134.74(15.11) |

131.31-138.17 |

Somali |

124.48(18.03) |

119.00-129.96 |

132.24(12.37) |

128.38-136.09 |

Others |

138.90(16.08) |

131.38-146.42 |

135.44(9.71) |

130.61-140.28 |

School grade |

Grade 5-8 |

135.01(14.70) |

132.59-137.43 |

.165

|

138.57(13.26) |

136.48-140.66 |

.012

|

Grade 9-10 |

131.77(18.83) |

128.68-134.86 |

135.99(14.65) |

133.60-138.39 |

Grade 11-12 |

135.52(16.94) |

131.67-139.36 |

141.98(10.74) |

139.26-144.71 |

Maternal education |

Non-educated |

132.72(16.60) |

130.58-134.86 |

.054

|

137.01(13.22) |

135.26-138.76 |

.037

|

Elementary |

131.94(19.51) |

124.78-139.09 |

137.85(12.77) |

133.40-142.31 |

Secondary |

138.71(13.79) |

135.49-141.93 |

141.77(14.20) |

138.72-144.81 |

College |

132.55(22.04) |

124.17-140.94 |

135.67(14.23) |

129.66-141.68 |

Paternal education |

Non-educated |

133.20(16.86) |

130.85-135.55 |

0.7820 |

138.24(12.50) |

136.49-139.99 |

0.844 |

Elementary |

134.95(14.79) |

128.22-141.68 |

134.67(17.23) |

121.43-147.91 |

Secondary |

133.81(17.14) |

130.22-137.40 |

137.79(15.89) |

134.68-140.89 |

College |

135.76(17.96) |

130.91-140.62 |

138.87(12.28) |

135.55-142.19 |

Mental health literacy level was inversely associated with age for both male and female respondents. Ethnicity also had a significant association with mental health literacy, and students who were Oromo (p<0.001), Somali (p<0.001) and other ethnicity or culture (p<0.01) exhibited lower mental health literacy than those with an Amhara ethnic/ cultural affiliation. Level of mental health literacy was associated with grade, and this effect was especially significant in female respondents (p<0.001). The effect of maternal and paternal education level was different in male and female participants, with male students showing a positive association and female students showing a negative association, despite there being an inconsistency in school grade between those with parents who were non-educated to those with college-level education (Table 3).

| Table 3: Socio-demographic factors associated with mental health literacy level among male and female adolescents in an urban, Ethiopia (bi-variate analysis adjusting for age showing coefficient and 95% CI) |

|

Male

Coefficient (95% CI) |

Female

Coefficient (95% CI) |

Age (yrs) |

-0.511(-1.307-0.285) |

-.425(-1.117-.267) |

Ethnicity/cultural affiliation |

Amhara (REF) |

|

|

Oromo |

-3.682(-7.493-.130)** |

-6.170(-9.586-(-2.753)** |

Somali |

-12.968(-18.377-(-7.560)** |

-8.638(-12.931-(-4.346)** |

Others |

-5.828(-13.355-1.699) |

-5.281(-11.894-1.332) |

School grade |

Grade 11-12 (REF) |

|

|

Grade 9-10 |

-2.621(-7.138-1.896) |

-6.190(-10.021-(-2.359)** |

Grade 5-8 |

-.86(-5.527-3.797) |

-3.645(-7.520-.230) |

Maternal education |

College (REF) |

|

|

Secondary education |

1.926(-5.662-9.514) |

5.885(-.357-12.127) |

Elementary education |

-3.661(-12.417-5.094) |

2.581(-4.562-9.723) |

Non- educated |

-2.262(-9.131-4.606) |

1.311(-4.507-7.128) |

Paternal education |

College (REF) |

|

|

Secondary education |

1.096(-4.653-6.845) |

-1.854(-6.337-2.629) |

Elementary education |

2.898(-5.561-11.356) |

-3.997(-13.520-5.526) |

Non-educated |

1.442(-3.666-6.550) |

-.882(-4.946-3.182) |

| ** P<0.001, * P<0.01 |

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis revealed the contribution of the socio-demographic factors to explaining the variability in mental health literacy. Ethnicity/cultural affiliation contributed about 6.5% of the variance of mental health literacy for female adolescents, and grade/education level contributed an additional 2.4% of the variability. Maternal and paternal education levels accounted for 2.1% of the variance in female adolescents' mental health literacy. Mental health literacy was independently associated with parental education level and was negatively associated with respondents' school grade. All factors combined accounted for 10.7% of the variability in mental health literacy of female adolescents (Table 4).

| Table 4: Socio-demographic Factors associated mental health literacy level among male and female adolescents in an Urban Ethiopia (multivariate linear regression analysis showing coefficient and 95% CI). |

Socio-demographic characteristics |

Male Adolescents |

Female Adolescents |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Coeff |

95%CI |

Coeff |

95% CI |

Coeff |

95% CI |

Coeff |

95%CI |

Coeff |

95%CI |

Coeff |

95%CI |

Ethnicity/cultural affiliation |

Amhara (REF) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oromo |

-3.682 |

-7.493, 0.130 |

-3.082 |

-7.150, .985 |

-3.214 |

-7.423, .996 |

-6.17 |

-9.586-(-2.753) |

-5.213 |

-8.701-(-1.725) |

-5.243 |

-8.912-(-1.575) |

Somali |

-12.968 |

-18.377, -7.560** |

-14.315 |

-19.987, -8.643 |

-14.569 |

-20.405, -8.733 |

-8.638 |

-12.931-(-4.346) |

-9.569 |

-13.971-(-5.168) |

-8.968 |

-13.465-(-4.471) |

Others |

-5.828 |

-13.355, 1.699 |

-5.092 |

-12.657, 2.473 |

-4.687 |

-12.296, 2.921 |

-5.281 |

-13.226 |

-4.962 |

-13.106 |

-4.668 |

-13.29 |

School grade |

Grade 11-12(REF) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grade 9-10 |

|

|

-3.945 |

-8.666, .777 |

-3.658 |

-8.447, 1.131 |

|

|

-5.872 |

-9.716-(-2.028) |

-5.898 |

-9.795-(-2.000) |

Grade 5-8 |

|

|

-4.316 |

-9.114, .482 |

-4.267 |

-9.113, .578 |

|

|

-5.13 |

-9.038-(-1.222) |

-4.941 |

-8.923-(-.959) |

Maternal education |

College (REF) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary education |

|

|

|

|

-0.285 |

-8.098, 7.528 |

|

|

|

|

6.078 |

-13.053 |

Elementary education |

|

|

|

|

-6.813 |

-16.259, 2.633 |

|

|

|

|

4.059 |

-15.609 |

Non- educated |

|

|

|

|

-4.741 |

-12.464, 2.982 |

|

|

|

|

2.238 |

-13.393 |

Paternal education |

College (REF) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary education |

|

|

|

|

3.356 |

-2.583, 9.295 |

|

|

|

|

-1.69 |

-9.83 |

Elementary education |

|

|

|

|

8.248 |

-.711, 17.208 |

|

|

|

|

-0.297 |

-19.753 |

Non-educated |

|

|

|

|

6.797 |

.872, 12.723 |

|

|

|

|

1.276 |

-9.792 |

R2 |

0.061 |

|

0.069 |

|

0.089 |

|

0.063 |

|

0.087 |

|

0.107 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.052 |

|

0.056 |

|

0.058 |

|

0.055 |

|

0.074 |

|

0.076 |

|

ΔR2 |

|

|

0.01 |

|

0.02 |

|

|

|

0.024 |

. |

0.021 |

|

F (p value) |

0.000 |

|

0.165 |

|

0.363 |

|

0.000 |

|

0.009 |

|

0.362 |

|

| Notes: Factors included in the models: Model 1: Ethnic/cultural affiliation; Model 2: Model 1+ school grade of the adolescents; Model 3: Model 2+ Parental educational (maternal and paternal education status). ** P<0.001, * P<0.01, Coeff = Coefficients |

Similarly, ethnicity/cultural affiliation accounted for 6.1% of the variance in mental health literacy for male adolescents, and grade/education level contributed an additional 1% of the variability. Maternal and paternal education levels combined accounted for 2% of the variance, almost identical to that in female adolescents. Mental health literacy was independently associated with parental education level and was negatively associated with participant school grade. All factors combined accounted for 10.7% of the variability in mental health literacy of male adolescents (Table 4). Mental health literacy was positively associated with school grade and maternal education level, and negatively associated with paternal education level. The above discussed socio-demographic factors explain 8.9% of the variability in male adolescents' mental health literacy (Table 4).

Discussion

This study assessed the level of adolescent mental health literacy in Dire Dawa city, Ethiopia and investigated its association with participant socio-demographic characteristics. The findings supported the hypothesis that these characteristics showed significant association with the adolescent mental health literacy, and are consistent with those previously reported around the world[49,52,58-61] Crucially, these findings contribute to a limited number of quantitative studies from middle and low-income countries, specifically Ethiopia.

This study found differences in the pattern of mental health literacy level between female and male adolescents. Female participants had overall slightly higher levels of mental health literacy (mean = 138.12±13.59) than male participants (mean = 133.64±16.95), consistent with other studies. A previous study showed the mental health literacy level of female Portuguese adolescents (mean=132.68±10.64) to be higher than their male counterparts (mean = 130.49±11.80) [49]. Gender differences in mental health literacy have been noted among students from Australia[54] and the USA[52,58] with studies consistently reporting lower mental health literacy among male participants. A nationwide survey from the USA reported males to have a more negative attitude than females regarding help-seeking behaviors related to mental ill-health[59].

Aside from the gender difference in mental health literacy levels, some other socio-demographic factors contributed to the difference, and further were demonstrated to differently affect male and female participants[52]. Ethnicity/cultural affiliation, school grade, and parental education level were associated with mental health literacy. These factors combined accounted for 10.7% and 8.9% of the variability in mental health literacy of female and male adolescents, respectively. Previous studies also reported similar effects of these characteristics[62-64]. However, this indicates that these factors account for a relatively minimal contribution of the variance in mental health literacy, emphasizing the need to understand the influence of other factors.

Schooling has been reported to have a significant effect on the mental health literacy of adolescents[17,65,66]. For example, a recent study in the USA indicated that adolescents from lower grades showed lower mental health literacy levels[66]. Chinese adolescents from middle grades had higher mental health literacy level than those in primary grades, and college students were higher still [67]. The present study was consistent with these findings. Mental health literacy level was associated with school grade in the present study, and this effect was especially significant in female adolescents (p<0.01). School grade contributed about 2.4% and 1% of the variability in mental health literacy of female and male adolescents, respectively, with a similar pattern of gender variation as discussed earlier.

Ethnicity and cultural affiliations have been shown to influence individuals' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs towards mental health issues[59,66,68,69]. Cultural factors are closely associated with race and ethnicity, with differing attitudes towards mental illness and disparities affecting adherence to mental health services[69]. In countries that exhibit multicultural and multi-ethnic diversity, such as Ethiopia, it is paramount to demonstrate an understanding of cultural differences when addressing mental health literacy.

The present study found an association between ethnicity/cultural affiliation and mental health literacy representing 6.5% and 6.1% of the variability in mental health literacy in female and male adolescents, respectively. Ethnic/cultural affiliation has been shown to be the single most significant factor predicting the use of mental health services [66] and predictive of mental health literacy[71-74] as well as health-related behaviors and other health outcomes[69]. The affiliations of Oromo (p<0.001), Somali (p<0.001) or another ethnicity/culture (p<0.01) were all negatively associated with mental health literacy, compared to participants with the Amhara ethnic or cultural affiliation. This is likely related to the belief norms and shared cultural values aligned with racial or ethnic identity strongly influencing social conventions, psychological processes, and behavior[69]. Additionally, in the Ethiopian context, ethnic and cultural affiliation is strongly interwoven with religious affiliation. Religious affiliation tends to dictate beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in many other aspects of life that will in turn affect mental health literacy and mental health outcomes[71]. This collection of beliefs, practices, and rituals with shared spiritual values determines an individual's beliefs, exposures, knowledge, and behavior towards health determinants and outcomes[72]. Previous cross-sectional studies have found significant and positive associations between religious involvement and mental health, with higher levels of social support and a lower prevalence of substance abuse[73]. There may be a positive effect of spirituality and religious involvement on mental health outcomes. For individuals who are active in religious practice, praying and reading spiritual materials may enhance positive mood through a sense of a connection with supreme power. Similarly, these individuals may be more likely to follow healthy lifestyles due to the positive social influence of their religious practice, promoting awareness about mental health issues[74]. Positive psychological and physical health outcomes have been reported from communities with high faith-based participation, where religious activities in many cases serve as an alternative source of support and treatment for individuals with mental ill-health[75]. Positive emotions have been related to religious belief and were reported to be higher in people who had firmly-held religious beliefs than those who were less religious[74]. A study in protestants and Catholics revealed a strong association between spirituality, social support, and higher life satisfaction[73]. Religions differ in doctrine and doctrine communication, with these factors also affecting approaches to psychology and mental health. For example, a study of Protestants, Jews, and Catholics revealed a correlation between social support and the salience of particular mental states in all three religious groups. In contrast, the association between spirituality, religious belief, and coping mechanisms was higher in Catholics and Protestants than in Jews[74].

There was a statistically significant association between mental health literacy and maternal and paternal education levels. Parents are often shown to be regulators of their children's wellbeing, playing a significant role in facilitating mental health literacy and mental health outcomes for their children. Hence, parental education level has a strong correlation with attitudes towards mental health treatment[59] which is likely also reflected in their children's views. The present study found that mental health literacy was differently associated with parental education level in male and female adolescents, accounting for 2.1% and 2% of the variance in mental health literacy of female and male adolescents, respectively. There is also existing evidence showing similar associations, for example, a study from Sri Lanka revealed that adolescents whose mothers attended college or higher education scored the lowest mental health literacy score, consistent with this present finding[76]. This may be due to educated mothers having significant work commitments, and consequently having less time to spend with their children during the critical mental and emotional development stages.

Conclusion

The present study has demonstrated several associations between mental health literacy and socio-demographic factors that are in agreement with previous evidence from high-income countries despite a paucity of comparative quantitative evidence from low-and-middle income countries, including Ethiopia. Female adolescents had slightly higher levels of mental health literacy than male adolescents. Mental health literacy level was also differently affected by socio-demographic factors for male and female adolescents. Ethnic/cultural affiliation, school grade, and parental education level combined accounted for about one tenth (~10%) of the variability in mental health literacy of both female and male adolescents. It is imperative to consider these differences in mental health literacy level for effective adolescent mental health promotion. These differences must be taken into account when designing interventions, likely with a need for more emphasis to be placed on the experiences of male adolescents. Promotion of mental health requires culturally congruent programs. In countries that exhibit multicultural and multi-ethnic diversity, and particularly where these are low-income countries, such as Ethiopia, it is paramount to demonstrate an understanding of multiple socio-demographic and cultural differences. Hence, the minimal contribution of these factors implies the need to understand the factors that contribute to the remaining proportions of the variability in adolescent mental health literacy and consideration of these factors is going to be key in understanding the differences in uptake of interventions.

Data availability: Data will be provided following a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests.

References

- Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Wright A. Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders Med J Aust. 2007 Oct 1;187(S7):S26-30. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01332.x.

- Jorm AF. Why We Need the Concept of Mental Health Literacy. Health Commun 2015;30:1166-8. doi:10.1080/10410236.2015.1037423.

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. Mental health literacy: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust 1997;166:182-6. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x.

- Jorm AF et al. Research on mental health literacy: What we know and what we still need to know. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:3-5. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01734.x.

- Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:396-401. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.5.396.

- Nutbeam D. Evaluating health promotion - progress, problems and solutions. Health Promot Int 1998;13:27-44. doi:10.1093/heapro/13.1.27.

- Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press. Copyright; 2013.

- Ratzan SC. Health literacy: Communication for the public good. Health Promot Int 2001;16:207-14. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.207.

- Parker RM, Gazmararian JA. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives Health Literacy: Essential for Health Communication Health Literacy: Essential for Health Communication. J Health Commun 2003;8:116-8. doi:10.1080/1081073090224956.

- McCray A. Promoting health literacy. J Am Med Informatics Assoc 2005;12:152-64. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1687.Addressing.

- Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Health literacy-identification and response. J Health Commun 2006;11:713-5. doi:10.1080/10810730601031090.

- Manganello JA. Health literacy and adolescents: A framework and agenda for future research. Health Educ Res 2008;23:840-7. doi:10.1093/her/cym069.

- Sørensen K, Van Den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012;12. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-80.

- Jorm AF. Mental health literacy; empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol 2012;67:231-43. doi:10.1037/a0025957.

- Johnson RL. Pathways to adolescent health: Early intervention. J Adolesc Heal 2002;31:240-50.

- Ryan P. Integrated theory of health behavior change: Background and intervention development. Clin Nurse Spec 2009;23:161-70. doi:10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373.

- Gonzalez JM, Alegria M, Prihoda TJ, Copeland LA, Zeber JE. How the relationship of attitudes toward mental health treatment and service use differs by age, gender, ethnicity/race and education. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2011;46:45-57. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0168-4.

- Lin HC, Chang CM. What motivates health information exchange in social media? The roles of the social cognitive theory and perceived interactivity. Inf Manag 2018. doi:10.1016/j.im.2018.03.006.

- Freeman JL, Caldwell PHY, Med B, Bennett PA, Scott KM. How Adolescents Search for and Appraise Online Health Information: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2018 Apr;195:244-255.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.11.031.

- Salam RA, Sc M, Das JK, A MB, Lassi ZS, Ph D, et al. Adolescent Health Interventions: Conclusions, Evidence Gaps, and Research Priorities. J Adolesc Health. 2016 Oct; 59(4 Suppl): S88-S92. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.006.

- Patton GC, Olsson CA, Skirbekk V, Saffery R, Wlodek ME, Azzopardi PS, et al. Adolescence and the next generation. Nature 2018;554:458–66. doi:10.1038/nature25759.

- La Maison C, Munhoz TN, Santos IS, Anselmi L, Barros FC, Matijasevich A. Prevalence and risk factors of psychiatric disorders in early adolescence: 2004 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018;53:685-97. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1516-z.

- Mills KL. Social development in adolescence: brain and behavioural changes. PQDT - UK Irel 2015.

- Broder J, Okan O, Bauer U, Bruland D, Schlupp S, Bollweg TM, et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017;17:1-25. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4267-y.

- David K, Park MJ, Mulye TP. The Mental Health of Adolescents: A National Profile, 2008. San Francisco: Natl. Adolesc. Health Inf. Cent. (NAHIC), Univ. Calif. 2008.

- Heike E et al. The Mental Health of Adolescents: A National children and adolescents with StresSOS using online or face-to-face interventions: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial within the ProHEAD Consortium. Trials 2019;20:94. doi:10.1186/s13063-018-3157-7.

- Tay JL. Effectiveness of information and communication technologies interventions to increase mental health literacy: A systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018:1024-37. doi:10.1111/eip.12695.

- Moreno MA, Radovic A. Technology and adolescent mental health. 2018. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69638-6.

- Kaess M, Bauer S. Editorial Promoting Help-seeking using E-Technology for ADolescents: The ProHEAD consortium. Trials 2019;20:72. doi:10.1186/s13063-018-3162-x.

- WHO. Adolescents: health risks and solutions. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions 2018.

- Atilola O. Level of community mental health literacy in sub-Saharan Africa: Current studies are limited in number, scope, spread, and cognizance of cultural nuances. Nord J Psychiatry 2015;69:93-101. doi:10.3109/08039488.2014.947319.

- Cortina M, Sodha A, Fazel M, Ramchandani PG. Prevalence of Child Mental Health Problems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(3):276-81.

- Zeleke WA, Nichols LM, Wondie Y. Mental Health in Ethiopia: an Exploratory Study of Counseling Alignment with Culture. Int J Adv Couns 2019;41:214-29. doi:10.1007/s10447-018-9368-5.

- CSA and UNICEF Ethiopia. Multidimensional Child Deprivation in Ethiopia. UNON Publ Serv Sect Nairobi - 2018.

- Kutcher S, Wei Y. Mental Health & High School Curriculum Guide (Guide v.3): Understanding mental health and mental illness. Teen Mental Health. Available at http://mentalhealthliteracy.org/schoolmhl/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Mental-Health-High-School-Curriculum-Guide.pdf 2017.

- Kutcher S, Bagnell A, Wei Y. Mental Health Literacy in Secondary Schools. A Canadian Approach. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2015;24:233-44. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.007.

- Kutcher S, Wei Y, Morgan C. Successful application of a Canadian mental health curriculum resource by usual classroom teachers in significantly and sustainably improving student mental health literacy. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:580-6.

- Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid: An international programme for early intervention. Early Interv Psychiatry 2008;2:55-61. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00056.x.

- GCYDCA. African School Mental Health Curriculum: Understanding Mental Health and Mental Illness: Guid Couns Youth Dev Cent Africa 2012.

- Caulfield A, Vatansever D, Lambert G, Van Bortel T. WHO guidance on mental health training: a systematic review of the progress for non-specialist health workers. BMJ Open 2019;9:bmjopen-2018-024059. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024059.

- Anderson M, Revie CW, Quail JM, Wodchis W, Oliveira C De, Osman M, et al. The effect of socio-demographic factors on mental health and addiction high-cost use: a retrospective, population-based study in Saskatchewan. Can J Public Health. 2018 Dec; 109(5-6): 810-820.

- Park SJ, Jeon HJ, Kim JY, Kim S, Roh S. Sociodemographic factors associated with the use of mental health services in depressed adults: results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES ). BMC Health Serv Res. 2014:1-10. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0645-7.

- Islam FMA. Psychological distress and its association with socio-demographic factors in a rural district in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019 Mar 13;14(3):e0212765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212765.

- Amirah SNMH, Husna H, Afnan MA, Suriani I, Nashriq AIMN. Sociodemographic Factors of Mental Health Literacy Among Housewives Living in Low Cost Apartments in Puchong, Selangor, Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences. 2020;16:121-5. Available at https://medic.upm.edu.my/upload/dokumen/2020011612053718_MJMHS_0323.pdf

- Cotton SM, Wright A, Harris MG, Jorm AF, McGorry PD. Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:790-6. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01885.x.

- Tully LA, Hawes DJ, Doyle FL, Sawyer MG, Dadds MR. A national child mental health literacy initiative is needed to reduce childhood mental health disorders. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry 2019;00:000486741882144. doi:10.1177/0004867418821440.

- Bhalerao S, Kadam P. Sample size calculation. Int J Ayurveda Res 2010;1:55. doi:10.4103/0974-7788.59946.

- O'Connor M, Casey L, Clough B. Measuring mental health literacy-a review of scale-based measures. J Ment Heal 2014;23:197-204. doi:10.3109/09638237.2014.910646.

- Campos L, Dias P, Palha F, Duarte A, Veiga E. Development and psychometric properties of a new questionnaire for assessing mental health literacy in young people. Univ Psychol 2016;15:61-72. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.upsy15-2.dppq.

- Bale J, Grove C, Costello S. Mental Health & Prevention A narrative literature review of child-focused mental health literacy attributes and scales Mental Health and Prevention. 2018;12:26-35. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2018.09.003.

- Lam LT. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: a population-based survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-8-26

- Dias P, Campos L, Almeida H, Palha F. Mental health literacy in young adults: Adaptation and psychometric properties of the mental health literacy questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071318.

- Wei Y, McGrath PJ, Hayden J, Kutcher S. Mental health literacy measures evaluating knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking: A scoping review. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0681-9.

- Tome G, de Matos MG, Camacho I. Mental Health Promotion in School Context - Validation of the es'cool scale for teachers. J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018;2: 1009. Available at https://meddocsonline.org/journal-of-psychiatry-and-behavioral-sciences/mental-health-promotion-in-school-context%E2%80%93Validation-of-the-ESCOOL-scale-for-teachers.pdf

- Bjornsen HN, Eilertsen MEB, Ringdal R, Espnes GA, Moksnes UK. Positive mental health literacy: Development and validation of a measure among Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health 2017;17:1-10. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4733-6.

- Reilly MO, Svirydzenka N, Adams S, Dogra N. Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018;53:647-62. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1530-1.

- Delacre M, Leys C, Mora YL, Lakens D. Taking parametric assumptions seriously: Arguments for the use of Welch's f-test instead of the classical f-test in one-way ANOVA. Int Rev Soc Psychol 2020;32:1-12. doi:10.5334/IRSP.198.

- Coles ME, Ravid A, Gibb B, George-Denn D, Bronstein LR, McLeod S. Adolescent Mental Health Literacy: Young People's Knowledge of Depression and Social Anxiety Disorder. J Adolesc Heal 2016;58:57-62. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.017.

- Gonzalez JM, Alegrid M, Prihoda TJ. How do attitudes toward mental health treatment vary by age, gender, and ethnicity/race in young adults? J Community Psychol 2005;33:611-29. doi:10.1002/jcop.20071.

- Cotton SM, Wright A, Harris MG, Jorm AF, McGorry PD. Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:790-6. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01885.x.

- Thomson KC, Guhn M, Richardson CG, Shoveller JA. Associations between household educational attainment and adolescent positive mental health in Canada. SSM - Popul Heal 2017;3:403-10. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.04.005.

- Lwin MO, Panchapakesan C, Sheldenkar A, Calvert GA, Lim LKS, Lu J. Determinants of eHealth Literacy among Adults in China. J Health Commun 2020;25:385-93. doi:10.1080/10810730.2020.1776422.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America's adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Education 2006;6:1-59.

- Venkataraman S, Patil R, Balasundaram S. Why mental health literacy still matters: a review. Int J Community Med Public Heal 2019;6:2723. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20192350.

- Furnham A, Annis J, Cleridou K. Gender differences in the mental health literacy of young people. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2014;26:283-92. doi:10.1515/ijamh-2013-0301.

- Lee HY, Hwang J, Ball JG, Lee J, Albright DL. Is health literacy associated with mental health literacy? Findings from Mental Health Literacy Scale. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2020;56:393-400. doi:10.1111/ppc.12447.

- Yu Y, Liu Z, Hu M, Liu X, Liu H, Yang JP. Assessment of mental health literacy using a multifaceted measure among a Chinese rural population 2015:1-9. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009054.

- Altweck L, Marshall TC, Ferenczi N, Lefringhausen K. Mental health literacy: a cross-cultural approach to knowledge and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and generalized anxiety disorder. Front Psychol 2015;6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01272.

- Abdullah T, Brown TL. Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:934-48. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003.

- Cinnirella M, Loewenthal KM. Religious and ethnic group influences on beliefs about mental illness: A qualitative interview study. Br J Med Psychol 1999;72:505-24. doi:10.1348/000711299160202.

- Estrada CAM, Lomboy MFTC, Gregorio ER, Amalia E, Leynes CR, Quizon RR, et al. Religious education can contribute to adolescent mental health in school settings. Int J Ment Health Syst 2019;13:1-6. doi:10.1186/s13033-019-0286-7.

- Ayvaci ER. Religious Barriers to Mental Healthcare. Am J Psychiatry Resid J 2016;11:11-3. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110706.

- Van Beveren L, Rutten K, Hensing G, Spyridoula N, Schønning V, Axelsson M, et al. A Critical Perspective on Mental Health News in Six European Countries: How Are Mental Health/Illness and Mental Health Literacy Rhetorically Constructed? Qual Health Res 2020;30:1362-78. doi:10.1177/1049732320912409.

- Behere PB, Das A, Yadav R, Behere AP. Religion and mental health. Indian J Psychiatry 2013;55. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.105526.

- Caplan S, Cordero C. Development of a faith-based mental health literacy program to improve treatment engagement among caribbean latinos in the Northeastern United States of America. Int Q Community Health Educ 2015;35:199-214. doi:10.1177/0272684X15581347.

- Attygalle UR, Perera H, Jayamanne BDW. Mental health literacy in adolescents: Ability to recognise problems, helpful interventions and outcomes. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2017;11:1-8. doi:10.1186/s13034-017-0176-1.

|