|

Case Report

A 39-year-old farmer

by profession reported dull pain (3–4/10 on the

Visual Analogue Scale) in the left lumbar area for

one year. An orthopaedic surgeon had previously

examined him, ruling out any conditions that would

have caused pain. Occasionally, he would use

over-the-counter pain relievers. There was no

other medical or surgical history of significance

in the past. On examination, there was no spinal

or lumbar deformity, and the renal angles were not

tender. The cough impulse over and inferior to the

left renal angle was, however, barely palpable.

|

| Figure

1: Ultrasound (USG ) image showing defect

in posterior fascia (red arrows) leading

to fatty left lumbar hernia (blue arrows).

|

An ultrasound study

of the left lumbar area revealed a defect in the

posterior fascia with herniation of

extraperitoneal fat (Figure 1), which increased

with the Valsalva manoeuvre. The neck of the

hernia measured approximately 13mm. There was no

herniation of bowel loops or other viscera. There

was no defect on the right side. A diagnosis of

Grynfelt-Lesshaft hernia was made, and due to a

lack of management experience with this rare

condition, the patient was attached to the

services of a tertiary healthcare facility, where

further imaging by MRI and open hernioplasty with

mesh implantation were successfully undertaken. At

the three-year follow-up, the patient was

satisfied and symptom-free.

|

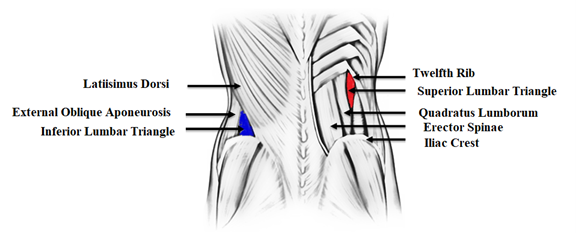

| Figure

2: Schematic diagram of anatomy of lumbar

area depicting superior lumbar triangle

(red colour) and inferior lumbar triangle

(blue colour) |

Discussion

Grynfelt-Lesshaft

hernia appears along the posterolateral abdominal

wall in the superior lumbar triangle (shown in red

in Figure 2), which is located posterior to the

lower pole of the left kidney. Posterior

(superficial) to this hernia is the latissimus

dorsi muscle, medial to it is the quadratus

lumborum muscle, and superior relation is formed

by the 12th rib [1]. In contrast, the inferior

lumbar triangle (shown in blue in Figure 2) is

bounded by the latissimus dorsi posteriorly, the

external oblique aponeurosis anteriorly, and the

iliac crest inferiorly [1].

It is a rare

condition, with only about 300 cases published in

the peer-reviewed literature, and most physicians

are not exposed to it during their training [2].

As a result, physicians frequently fail to

recognize this hernia or misdiagnose it as a

lipoma, which causes treatment delays and an

increase in morbidity [3]. Barbette had suggested

the possibility of lumbar hernias in 1672, and the

first case was reported by Garangeot in 1731. The

boundaries of the inferior and superior lumbar

triangles were delineated by Petit and Grynfeltt

in 1783 and 1866, respectively [4].

On the basis of

origin, lumbar hernias have been classified as

congenital (20%) or acquired (80%). The congenital

hernias are believed to form during embryologic

development, when the invasion of the somatopleure

by the aponeuroses of the layered abdominal

muscles results in the creation of potentially

weak areas If acquired, the hernias may be either

primary (55%) or else secondary (25%) [4]. The

most common cause of primarily acquired lumbar

hernias is increased intra-abdominal pressure,

with predisposing factors such as old age, chronic

lung disease, extremes of weight, muscular

atrophy, and professions that involve lumbar

constraints. Secondarily acquired lumbar hernias

are associated with trauma, prior surgical

incisions, and infection or abscess formation

[1,4].

The patient may be

asymptomatic or else present with discomfort,

dragging sensations, flank swelling, and, rarely,

gut obstruction. These hernias may grow to huge

dimensions and have an inherent tendency of

getting larger over time. Retroperitoneal fat,

kidney, colon, or, less frequently, small bowel,

omentum, ovary, spleen, or appendix, may be

contained in the hernia [4]. Impulses on coughing

may be visible or palpable over the hernia, and if

it contains bowel loops, auscultation may reveal

audible bowel sounds over it.

In the presented

case, the hernia was documented by

ultrasonography, though this modality may fail to

detect the hernia due to the presence of body fat

in this region and a lower index of suspicion [4].

CT-scan and MRI studies can lead to accurate

diagnosis by proper delineation of the anatomy and

identification of defects in the muscular and

fascial layers [4]. These imaging modalities can

also distinguish a hernia from other differential

diagnoses, such as hematoma, abscess, or

soft-tissue tumour [5].

Surgical repair of

these hernias should be undertaken as early as

possible to avoid incarceration and strangulation

[4]. Bowel incarceration is reported in 25% of

cases, though strangulation is rare due to the

wideness of the hernial neck [4]. Eliminating the

defect and building a sturdy, elastic abdominal

wall that can sustain the strain of regular

physical activity are the two main objectives of

hernia repair [4]. Due to the rarity of this

hernia, there is no clear consensus on the type of

repair, but the classic repair published in the

literature uses the open surgical approach, where

tension-free closure of the defect is performed

either directly or using prosthetic mesh [6]. A

transabdominal or extraperitoneal laparoscopic

approach are the alternatives. It is advantageous

for the mesh to be positioned extra-peritoneally

since no bony anchorage is required. The sound

physiological principle of diffusion of the entire

intra-abdominal pressure on each square inch of

the implanted mesh serves as the foundation for

laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal mesh

repair, which has also been documented in the

literature [7]. It is a tensionless repair that

offers the patient rapid recuperation and improved

cosmesis.

There is a proposal

by some experts to base the surgical approach on a

classification that takes into account six

characteristics of the hernia: size, location,

content, aetiology, muscular atrophy, and the

existence or otherwise of a recurrence [8]. If the

patient reports bowel obstruction and there is

doubt about the viability of the bowel, laparotomy

has been suggested as a surgical approach to allow

resection of the non-viable bowel and adequate

peritoneal lavage [9].

Acknowledgements

The patient's consent to the publication of this

case study and its accompanying images is

gratefully acknowledged by the author.

References

- Stamatiou D, Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis LJ,

Mirilas P. Lumbar hernia: surgical anatomy,

embryology, and technique of repair. Am

Surg. 2009 Mar; 75(3):202-7.

- Ploneda-Valencia CF, Cordero-Estrada E1,

Castañeda-González LG et al. Grynfelt-Lesshaft

hernia a case report and review of the

literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2016

Apr;7:104-6.

- Ahmed ST, Ranjan R, Saha SB, Singh B. Lumbar

hernia: a diagnostic dilemma. BMJ Case Rep.

2014 Apr 15;2014:bcr2013202085. doi:

10.1136/bcr-2013-202085.

- Sharma P. Lumbar Hernia. Med J Armed

Forces India. 2009 Apr; 65(2):178-9.

- Meinke AK. Totally extraperitoneal

laparoendoscopic repair of lumbar hernia. Surg

Endosc. 2003;17:734–737.

- Shadhu K, Ramlagun D, Chen S, Liu L. Surgical

approach towards Grynfelt hernia: A single

center experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018

Aug; 97(33):e11928.

- Heniford BT, Iannitti DA, Gagner M.

Laparoscopic inferior and superior lumbar hernia

repair. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1141–1144.

- Moreno-Egea A, Baena E, Calle M,Martinez J,

Albasini J. Controversies in the current

management of lumbar hernias. Arch Surg. 2007;142(1):82–88.

- Stupalkowska W, Powell-Brett SF, Krijgsman B.

Grynfeltt-Lesshaft lumbar hernia: a rare cause

of bowel obstruction misdiagnosed as a lipoma. J

Surg Case Rep. 2017 Sep 7;2017(9):rjx173.

doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx173.

|