|

Introduction

Healthcare

expenditure plays a crucial role in determining

the quality and accessibility of healthcare

services within a country. However, Healthcare

must be a priority, which calls for either more

spending and investment or a more proactive

approach to boosting individual state economies so

that more money can be allocated to healthcare

sector development [1]. Public healthcare services

significantly influence people's health status,

and public healthcare infrastructure is one of the

key factors affecting health outcomes in a nation

[2]. To enhance India's ranking on the human

development index, the Indian government must

manage its public expenditures effectively [3]. In

India, the healthcare sector is confronted with

numerous challenges, including a vast and diverse

population, inadequate infrastructure, and limited

financial resources. The allocation of healthcare

expenditure across different states can vary

significantly, reflecting variations in economic

development, healthcare infrastructure, and health

outcomes [4]. Understanding the patterns of

healthcare expenditure in Indian states is

essential for formulating effective policies and

interventions to improve healthcare delivery and

ensure equitable access to healthcare services.

Healthcare expenditure is a fundamental aspect of

healthcare systems worldwide, serving as a key

determinant of healthcare outcomes and access to

quality care [5]. In the context of India, a

country with a population of over 1.3 billion

people and immense diversity, healthcare

expenditure patterns are critical in addressing

the healthcare needs of its states and population

[6].

India's healthcare

system is characterized by a complex mix of public

and private sector participation, with varying

degrees of resource allocation and service

delivery. The Indian government has made efforts

to improve healthcare infrastructure and services,

notably through initiatives such as the National

Health Mission and the Ayushman Bharat scheme.

Investment in health expenditure has a positive

degree of long-run correlation with life

expectancy rate, while it is negatively associated

with the infant mortality rate [7]. However,

challenges persist, including disparities in

healthcare expenditure across states, inadequate

public healthcare infrastructure, and financial

constraints. The allocation of public funds to the

healthcare sector is a crucial determinant of

healthcare expenditure. Governments at the state

and central levels need to prioritize healthcare

spending in the NER states to bridge the

healthcare infrastructure gaps and improve access

to quality healthcare services. Increased

government spending on healthcare can lead to

better healthcare outcomes and increased

expenditure overall. To gain insights into the

allocation of healthcare expenditure in Indian

states, it is essential to examine comprehensive

data that may, directly and indirectly, captures

the healthcare spending patterns. Such data can

include government budgetary allocations, total

revenue collection, total social expenditure as

well as debt and fiscal deficit accounts.

Analyzing this data enables policymakers and

researchers to assess the adequacy and efficiency

of healthcare spending, identify areas of

improvement, and develop evidence-based strategies

to enhance healthcare delivery and access.

This study aims to

explore the macroeconomic policy impact on

healthcare expenditure patterns in northeast

India. By examining the trends and variations in

healthcare expenditure, we can gain valuable

insights into the resource allocation dynamics and

identify potential areas for policy interventions.

Materials and Methods

Utilizing the data

from the Economic and Political Weekly Research

Foundation, the present study included eight NER

states of India, namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam,

Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and

Tripura, for the period of 1990-91–2019-20. The

chosen fiscal variables, including total social

sector expenditure, per-capita gross state

domestic product, total revenue receipts, and

states’ own and non-tax revenue, are regarded as

macroeconomic factors of an economy and may have a

positive impact on healthcare spending. In

contrast, variables like internal debt and the

fiscal deficit may have a negative impact on

healthcare spending.

|

Table 1: Summary

Statistics

|

|

Variable(s)

|

Description

|

Mean

|

Max

|

Min

|

Std. Dev.

|

Correlation

|

|

PHE

|

Public Health Expenditure to GSDP

|

1.329

|

6.208

|

0.160

|

0.064

|

1

|

|

TSE

|

Total Social Expenditure to GSDP

|

8.540

|

26.820

|

1.136

|

0.323

|

0.925

|

|

PCGSDP

|

Per Capita Gross State Domestic Product

|

57986.911

|

292235

|

15060

|

2918.165

|

0.395

|

|

TRR

|

Total Revenue Receipts to GSDP

|

29.947

|

97.122

|

2.582

|

1.210

|

0.847

|

|

SOTR

|

States’ Own Tax Revenue to GSDP

|

2.454

|

10.958

|

0.081

|

0.131

|

0.641

|

|

NTR

|

States’ Own Non Tax Revenue to GSDP

|

3.666

|

41.736

|

0.313

|

0.512

|

0.005

|

|

IND

|

Internal Debt to GSDP

|

15.392

|

49.595

|

0.593

|

0.720

|

0.694

|

|

GFD

|

Gross Fiscal Deficit to GSDP

|

2.925

|

13.049

|

-5.764

|

0.194

|

0.278

|

|

CGR

|

Central Grants

|

23959.333

|

207056.1

|

963.3

|

1792.744

|

0.360

|

|

Source: Authors’

Calculation based on EPWRF data series

(1990-91 to 2019-20).

|

Table 1 represents

the description and summary statistics of the

selected variables, which shows that the mean of

PHE is 1.329 per cent while the mean of total

revenue receipts is 29.947 per cent. There is a

huge difference in the maximum and minimum value

of total revenue receipts and PHE, respectively.

It shows that most of the tax revenue across the

states is derived from the low contribution of

states’ own tax revenue. Huge differences have

been also observed in maximum and minimum value of

internal debt and gross fiscal deficit, indicating

inter-state variation over time. Besides, positive

correlation is found between PHE with other

explanatory variables such as TSE, PCGSDP, TRR,

SOTR, NTR, CGR, as well as IND and GFD (as

described in Table 1).

All the variables are taking the base year of

2011–2012 at constant prices.

Prior to

formulating the VECM model for the analysis, the

following model has been used, covering the nine

variables as mentioned in (Table 1):

PHE = β0+

β1TSEit+ β2PCGSDPit

+ β3TRRit + β4SOTRit

+ β5NTRit + β6INDit

+ β7GFDit + β8CGRit

+ µit(1)

Sigma

Convergence Analysis

To check the

convergence tendency of the variables of public

healthcare expenditure and the macroeconomic

variables, such as total social sector

expenditure, per capita GSDP, total revenue

receipts, states’ own tax revenue and

non-tax-revenue, internal debt, fiscal deficit and

central grants to states, sigma convergence

analysis has been applied. The sigma “σ”-

convergence approach can be employed, through the

help of the coefficient of variation (CV) over

time. For the present case, all the eight North

Eastern states were taken together to examine

their tendency of convergence/divergence trend

from 1990-91 to 2019-20. The following formula has

been used for the analysis:

(2)

(2)

In this context,

'n' denotes the total number of objects,

specifically referring to the eight states under

consideration. 't' represents the specific year

being discussed, while 'i' represents each

individual member state being examined. Lastly,

'y' represents the cumulative fiscal pressure

being analyzed.

Vector

Error Correction Model (VECM) Approach

Further, the

present paper uses the VECM approach for

forecasting macroeconomic variables. The VECM is a

widely used econometric model that allows for the

analysis of long-run relationships and short-run

dynamics among multiple time series variables. By

incorporating both the cointegration and error

correction mechanism, the VECM provides a powerful

framework for modelling and forecasting

macroeconomic variables. In this study, we apply

the VECM methodology to a set of key macroeconomic

indicators and evaluate its forecasting

performance against alternative approaches. The

VECM analysis shows the results of short as well

as long-run impact, despite the stationarity

properties of the series. The specification of the

VECM model is as follows:

(3)

(3)

The symbol of ‘Δ’ denotes first-difference order,

and  is an error correction term with no correlation

with the independent variables of the model. The

long-run relationship of the variables can be

achieved if b0,i= 0 is

negative and it is rejected in the model. On the

other hand, the short-term relationship among the

variables can be observed, if b 1,i =

0 is rejected, through the Wald test.

is an error correction term with no correlation

with the independent variables of the model. The

long-run relationship of the variables can be

achieved if b0,i= 0 is

negative and it is rejected in the model. On the

other hand, the short-term relationship among the

variables can be observed, if b 1,i =

0 is rejected, through the Wald test.

Discussion

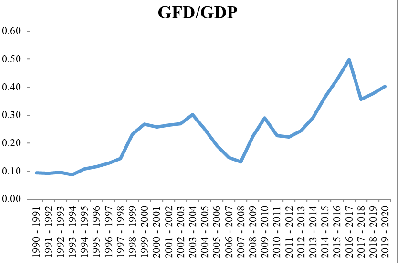

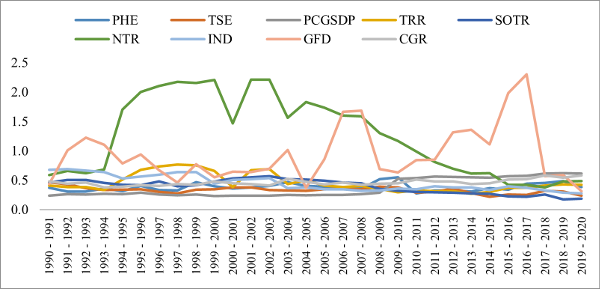

Macroeconomic Policies and the

Public Health Expenditure: Indian States

The potential of a

rise in India's public health expenditures is

increased by the combination of improved growth

prospects at least over the medium term and fiscal

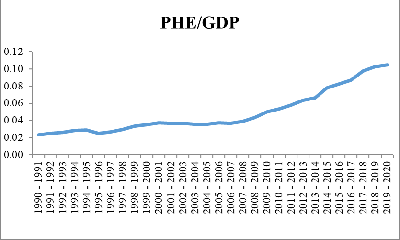

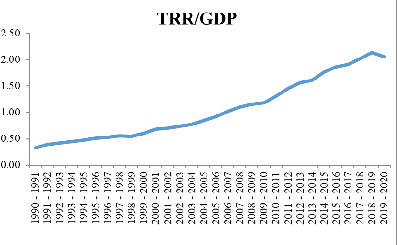

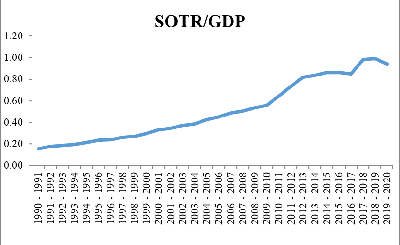

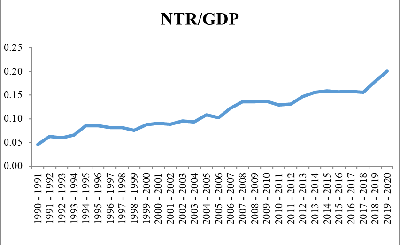

consolidation [8]. Since the 1990s there is

changing trends of macroeconomic factors such as

total social expenditure, per capita gross

domestic product (GDP) as a proxy of economic

growth, internal debt, fiscal deficit, central

grants to respective states, and revenue account

through total revenue receipts, states’ own and

non-tax revenue and public health expenditure

across the Indian states (Figure1).

For the development of healthcare sector, the

macroeconomic factors play a vital role in the

contribution of fiscal space [9]. The growth trend

of PHE to GDP has consistently increased and it

increases from 0.2 in 1990-91 to 0.10 per cent in

2019-20. The trend of public health expenditure to

GDP is increased with total social sector

expenditure in the ratio of GDP. The increasing

trend of total revenue receipts and central grants

with increasing states’ own tax and non-tax

revenue has been observed over time, which can be

considered as the prospective source for financing

the healthcare system. A similar study has found

that Indian states being heterogeneous in nature

and having low tax revenue, there is a positive

impact of tax revenue on healthcare expenditure

growth over time [10].

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: Public Health

Expenditure and Macroeconomic Variables:

Trends Analysis

Source: Authors’ Calculation based on EPWRF

data series (1990-91 to 2019-20). |

However, with the

increasing trend of the PHE-GDP ratio, the fiscal

deficit and internal debt in ratio of GDP also

increased, it may be considered that the debt and

deficit amount is used in development expenditure

purpose like public health and education. Despite

of growth of revenue trend, the growth trend of

PHE is slightly declined during 2001-02 to 2004-05

due to higher fiscal deficit but it increased

after the reduction of fiscal deficit in 2007-08.

Further, there is fluctuation in terms of per

capita GDP of Indian states over time. Although, a

positive bi-directional relationship has been

found for developing countries. The effect of

health expenditures on economic growth justifies

the need for governments to implement policies

that encourage health expenditures to create a

healthier and more productive society in order to

foster the development and expansion of the

economy in developing nations [11].

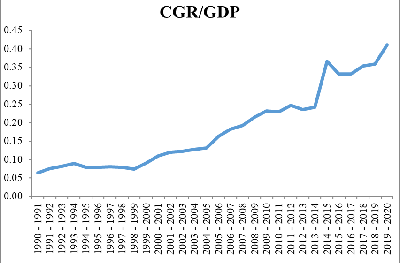

Tendency

of Convergence: “σ” Analysis

As stated in the

methodology section, the assessment of

convergence/divergence through σ-convergence can

be carried out using the coefficient of variation

method. The results of the coefficient of

variation over time for all the northeastern

states together reveal that macroeconomic

variables, including states' own tax revenue,

internal debt, public health expenditure, and

total social sector expenditure, tend to converge

during the period of 2019-20. The variable of

fiscal deficit has exhibited greater fluctuations

compared to other variables. However, it is

noteworthy that fiscal deficit has displayed a

declining trend since the fiscal year 2016-17.

Additionally, it is observed that variables such

as per capita GSDP, non-tax revenue, and central

grants to states have shown a tendency to diverge

over time. Therefore, it is evident that the

northeastern states reveal a similar pattern in

terms of their performance in macroeconomic

factors, as they are all economically, socially,

and geographically underdeveloped.

|

Figure 2: Sigma Convergence

Analysis from 1990-91 to 2019-20

Source: Authors’ Calculation based on EPWRF

data series (1990-91 to 2019-20). |

Macroeconomic

Factors Response to PHE from 1990-91 to

2019-20

Prior to the

empirical analysis of the model, the panel unit

root test has been applied for all the nine

variables of the study, by using Levin-Lin-Chu

“LLC”, [12] and Im-Pesaran-Shin “IPS” [13] test.

The LLC test is an extension of the Augmented

Dicky Fuller (ADF) test for panel data. It assumes

the presence of a common unit root across all

individuals, while the IPS test allows for both a

common unit root and individual-specific unit

roots, considering cross-sectional dependence and

heterogeneity. Afterwards, the long-term

co-movement between the variables has checked

through the Johansen cointegration test. The

Johansen cointegration test enables the analysts

to comprehend the interdependencies and dynamics

between various economic variables and to make

better decisions based on the discovered long-term

relationships. Based on the results of unit root

and cointegration test, further long-run and

short-run impact of the macroeconomic variables on

public health expenditure can be analyzed by

utilizing the VECM approach.

Panel

Unit-Root Tests

The result of panel

unit root tests is presented in Table 2,

where null shows non-stationarity and the

alternative hypothesis indicates stationarity in

the series. The variables, viz. public health

expenditure, total social sector expenditure, per

capita GSDP, states’ own tax revenue, internal

debt, and central grants to states are panel

non-stationary and total revenue receipts, states’

own non-tax revenue and fiscal deficit are

stationary at the level in LLC test. Further, in

case of the IPS test, except for states’ own

non-tax revenue and fiscal deficit, all the other

variables are panel non-stationary at level.

Besides, all the variables are stationary at first

difference level in case of both LLC and IPS

tests.

|

Table 2:

Results of Panel Unit Root Test

|

|

Trend &

Intercept

|

|

Variable(s)

|

LLC

|

IPS

|

|

I(0)

|

(1)

|

I(0)

|

(1)

|

|

PHE

|

-0.443

|

-11.716***

|

2.338

|

-11.978***

|

|

TSE

|

-0.334

|

-14.027***

|

1.035

|

-13.414***

|

|

PCGSDP

|

2.766

|

-9.056***

|

5.169

|

-10.518***

|

|

TRR

|

-1.697**

|

-10.861***

|

0.120

|

-11.255***

|

|

SOTR

|

4.419

|

-2.703***

|

9.496

|

-6.832***

|

|

NTR

|

-4.258***

|

-2.944***

|

-4.806***

|

-8.260***

|

|

IND

|

1.340

|

-6.242***

|

-0.477

|

-6.948***

|

|

GFD

|

-2.154***

|

-8.800***

|

-3.457***

|

-11.511***

|

|

CGR

|

0.643

|

-10.742***

|

-0.830

|

-13.585***

|

|

Source: Authors’

Calculation based on EPWRF data series

(1990-91 to 2019-20)

Note: ***, ** indicates significance level

of 1 & 5 per cent.

|

Panel Cointegration Tests

The significance of

cointegration test lies in its ability to

facilitate the establishment of a meaningful and

consistent association between variables, even in

the absence of direct causal linkage. Table 3

demonstrates the results of the Johansen

cointegration test [14], which indicates the

long-term relationships between PHE and other

macroeconomic variables (as eq.1). The

results of the test show that there is significant

long-run co-movement among public healthcare

expenditure and the macroeconomic variables such

as total social sector expenditure, per capita

GSDP, total revenue receipts, states’ own tax and

non-tax revenue, internal debt, fiscal deficit and

central grants to states, implying that the public

health expenditure would be sustained in the

long-run with increase or decrease in total social

sector expenditure, expansion of revenue

generation, lower fiscal deficit and internal debt

of the states.

|

Table 3: Results of Panel

Cointegration Tests

|

|

Null hypothesis (H0): No

cointgration

Alternative hypothesis (H1):

Presence of cointegration

|

|

Hypothesized No. of CE(s)

|

Trace Test

|

Max-Eigen Test

|

|

None

|

94.88***

|

574.4***

|

|

At most 1

|

595.3***

|

236.8***

|

|

At most 2

|

303.7***

|

213.5***

|

|

At most 3

|

314.4***

|

134.8***

|

|

At most 4

|

205.2***

|

108.0***

|

|

At most 5

|

120.8***

|

74.23***

|

|

At most 6

|

6026***

|

38.11***

|

|

At most 7

|

36.59***

|

34.08***

|

|

At most 8

|

20.69

|

20.69

|

|

Source: Authors’ Calculation based on

EPWRF data series (1990-91 to 2019-20)

Note: *** indicates significance level of

1 per cent.

|

Macroeconomic

Factors on Public Health Expenditure Growth:

Long-run Impact

This section

summarizes the key findings of the study and

emphasizes the value of the VECM approach in

forecasting macroeconomic variables. We highlight

its advantages over traditional models and its

potential to capture both short-run dynamics and

long-run equilibrium relationships. The long-run

impact of macroeconomic factors on public health

expenditure growth is presented in Table 4. The

coefficient of total social sector expenditure is

positive and significant at one per cent level,

indicating that an increase in TSE leads to 5 per

cent increase in PHE. Surprisingly, the per capita

GSDP is negative with -1.49 points at one per cent

significant level. A similar study found that the

northeastern states namely, Nagaland, Manipur and

Meghalaya exhibit a regressive trend in the change

of public healthcare financing. This is attributed

to the moderate increase in the states' domestic

product, which is accompanied by a decline in

government health expenditure [15]. Further, total

revenue receipts and states’ own tax revenue are

positively significant, implying an increase in

both the indicators leads to 3.8 and 11.9 per cent

increase in PHE, respectively. The coefficients of

states’ own non-tax revenue and central grants to

states have negative and significant impact on the

growth of PHE in the long run. Although, all the

eight northeastern states are getting higher

central grants, being in the list of Special

Category States, due to various disadvantageous

features [16]. The northeastern states might fail

to increase healthcare expenditure due to their

lack of physical and social infrastructure

facilities. Besides, the coefficient of internal

debt is negative, while the fiscal deficit has

positive impact on PHE at ten per cent level.

Thus, it is clear that an increase in total social

sector expenditure and revenue receipts have

favourable impact on the growth of PHE for the

North Eastern states in the long run.

|

Table 4:

Results Panel VECM Tests: Long-run

Impact

|

|

Dependent = PHE

|

|

Variable(s)

|

Coeff.

|

Std. Error

|

T-stat

|

Prob.

|

|

TSE

|

0.050***

|

0.014

|

3.391

|

0.0008

|

|

PCGSDP

|

-1.492***

|

5.663

|

-2.635

|

0.0090

|

|

TRR

|

0.038***

|

0.004

|

9.139

|

0.0000

|

|

SOTR

|

0.119***

|

0.019

|

6.193

|

0.0000

|

|

NTR

|

-0.042***

|

0.004

|

-8.668

|

0.0000

|

|

IND

|

-0.014***

|

0.003

|

-4.120

|

0.0001

|

|

GFD

|

0.012*

|

0.008

|

1.724

|

0.0861

|

|

CGR

|

-4.010***

|

1.041

|

-3.850

|

0.0002

|

|

Source: Authors’

Calculation based on EPWRF data series

(1990-91 to 2019-20)

Note: ***, * indicates significance level

of 1 & 10 per cent.

|

Macroeconomic

Factors on Public Health Expenditure Growth:

Short-run Impact

Due to lack of

resources and lack of proper utilization of the

existing resources, low-income category states of

India were lagging behind in public sector

efficiency [17]. The short-run impact of

macroeconomic variables on PHE has been analysed

through the VECM approach. Table 5 explains that

the model that has short-run impact and the error

correction term value is -0.052 at one per cent

significant level. The coefficients of total

social sector expenditure and states’ own tax

revenue have positive short run impacts on the

growth of public health expenditure. Additionally,

PHE has been negatively affected, through central

grants. Further, fiscal deficit has negatively and

significant effect on PHE in the short-run. The

other variables such as total revenue receipts,

per capita GSDP, states’ own non-tax revenue and

internal debt have no short-run impact on PHE.

Thus, it is clear that an increase in total social

sector expenditure and revenue receipts also has

favourable impact on the growth of PHE for the

northeastern states in the short run.

|

Table 5:

Results Panel VECM Tests: Short-run

Impact

|

|

Dependent = PHE

|

|

Variable(s)

|

Coeff.

|

Std. Error

|

T-stat

|

Prob.

|

|

TSE

|

0.064**

|

0.028

|

2.222

|

0.026

|

|

TSEt_1

|

0.082***

|

0.030

|

2.697

|

0.007

|

|

PCGSDP

|

-2.328

|

3.965

|

-0.587

|

0.557

|

|

PGSDP_1

|

-6.438

|

3.949

|

-1.629

|

0.103

|

|

TRR

|

-0.001

|

0.008

|

-0.193

|

0.846

|

|

TRR_1

|

-0.002

|

0.009

|

-0.234

|

0.814

|

|

SOTR

|

0.083***

|

0.033

|

2.511

|

0.012

|

|

SOTR_1

|

0.112***

|

0.043

|

-2.607

|

0.009

|

|

NTR

|

0.004

|

0.010

|

0.049

|

0.960

|

|

NTR_1

|

0.001

|

0.010

|

0.127

|

0.898

|

|

IND

|

-0.003

|

0.009

|

-0.308

|

0.757

|

|

IND_1

|

-0.003

|

0.009

|

-0.032

|

0.973

|

|

GFD

|

-0.007

|

0.009

|

-0.777

|

0.436

|

|

GFD_1

|

-0.007***

|

0.009

|

-2.606

|

0.009

|

|

CGR

|

-8.128***

|

3.125

|

-2.600

|

0.009

|

|

CGR_1

|

-6.900***

|

2.959

|

-2.331

|

0.019

|

|

ECMt-1

|

-0.052***

|

0.013

|

3.973

|

0.001

|

|

Source: Authors’

Calculation based on EPWRF data series

(1990-91 to 2019-20)

Note: ***, ** indicates significance level

of 1 & 5 per cent.

|

Conclusion

The relationship

between macroeconomic factors and healthcare

expenditure can be complex and can vary across

countries depending on their healthcare systems,

policies, and socio-economic factors, which need

to carefully balance these factors to ensure

sustainable and equitable healthcare spending. The

present study examines the impact of macroeconomic

factors i.e. economic growth, revenue account,

internal debt, fiscal deficit, and central grants

on the public health expenditure in evaluating

financial space for health in the northeastern

states of India from 1990-91 to 2019-20. The study

observed that the trend of public health

expenditure to GDP is increased with total social

sector expenditure, total revenue receipts and

central grants with increasing states’ own tax and

non-tax revenue in ratio of GDP, which can be

considered as the prospective source for financing

healthcare system of Indian states. Besides, the

macroeconomic factors of the northeastern states,

such as states' own tax revenue, internal debt,

public health expenditure, and total social sector

expenditure tend to converge during 2019-20.

Fiscal deficit fluctuates more than other

indicators but tends to converge since 2015-16.

Further, per capita GSDP, non-tax revenue, and

central transfers to states are diverging over

time. The study results based on the VECM approach

highlight that with the increase in total social

sector expenditure and all the revenue receipts

heads viz. total receipts and states’ own and

non-tax revenue have favourable impact on the

growth of PHE for the northeastern states in both

long-run and short-run. The central grants to the

northeastern states have both short-run and

long-run impacts on PHE. Thus, it can be said that

being key indicators of economic development, the

macroeconomic factors lead to a significant impact

on healthcare expenditure. The variables like

fiscal deficit and internal debt have no short-run

impact but they have long-run significant impact

on the growth of healthcare expenditure. Thus, the

findings of the study suggest that the government

of northeast India should develop such schemes for

healthcare development with higher infrastructure

facilities, including hospitals, clinics, and

healthcare training institutes. Increased

investment in infrastructure can contribute to

higher healthcare expenditure.

References

- Apergis N, Padhi P. Health expenses and

economic growth: convergence dynamics across the

Indian States. International Journal of

Health Care Finance and Economics. 2013

Dec;13:261-77.

- Neog N, Baruah M, Biswas K, Hazarika H.

An Inter District Analysis of Public Healthcare

Infrastructure Disparities in Assam. Online

Journal of Health Allied Sciences.

2023;22(1):1.

- Ray M, Sarangi M. Causal linkage between

social sector expenditure and economic growth:

Evidence from India. Indian Journal of

Economics and Business. 2021

Jul;20(2):463-73.

- Murugan K, Sivagnanam KJ. Public Expenditure

and Economic Development of Indian States: A

Panel Data Analysis. Journal of Economic

Policy and Research. 2019 Apr

1;14(2):69-79.

- Dwivedi R, Pradhan J. Does equity in

healthcare spending exist among Indian states?

Explaining regional variations from national

sample survey data. International Journal

for Equity in Health. 2017 Dec;16:1-2.

- Dash SK, Mohanty AR. The impact of income on

public health and education expenditure:

Evidence from the Indian states. Journal of

Public Affairs. 2022 Dec;22:e2757.

- Varkey RS, Joy J, Panda PK. Health

infrastructure, health outcome and economic

growth: evidence from Indian major states.

Health. 2020;7(11):2020.

- Misra BS, Panda AK. Public Expenditure on

Health and Health Outcomes: The Experience of

the Indian States. ILAKSHAN. 2007:43.

- Behera DK, Dash U. The impact of macroeconomic

policies on the growth of public health

expenditure: An empirical assessment from the

Indian states. Cogent Economics &

Finance. 2018 Jan 1;6(1):1435443.

- Behera DK, Dash U. Impact of GDP and tax

revenue on health care financing: An empirical

investigation from Indian states. Theoretical

& Applied Economics.

2017;2(611):249-66.

- Halıcı-Tülüce NS, Doğan İ, Dumrul C. Is income

relevant for health expenditure and economic

growth nexus? International Journal of

Health Economics and Management. 2016

Mar;16:23-49.

- Levin A, Lin CF, Chu CS. Unit root tests in

panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample

properties. Journal of Econometrics. 2002

May 1;108(1):1-24.

- Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y. Testing for unit

roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of

Econometrics. 2003 Jul 1;115(1):53-74.

- Johansen S. Estimation and hypothesis testing

of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector

autoregressive models. Econometrica: Journal

of the Econometric Society. 1991 Nov

1:1551-80.

- Behera DK, Dash U. Effects of economic growth

towards government health financing of Indian

states: an assessment from a fiscal space

perspective. Journal of Asian Public Policy.

2019 May 4;12(2):206-27.

- Saikia B, Roy CS, Shah S. FRBM Act and Fiscal

Performance of the Special Category States of

India: A Trend Analysis. Social Change and

Development. 2022:1-17.

- Mohanty RK, Bhanumurthy NR. Assessing public

expenditure efficiency at Indian states.

National Institute of Public Finance and Policy,

New Delhi, NIPFP Working Paper. 2018 Mar 19;225.

|