|

Introduction

Cesarean

section is the delivery of fetus through abdominal

uterine incision after fetal viability, 28 weeks

and above. The rising cesarean section is a global

concern, and the rate has exceeded 30% in some

regions. As per the World Health Organization

(WHO) statement in the year 1985, C-section rate

higher than 10–15% is not justified for any

region.(1) Even after thirty years of the

publication of the WHO guidelines in the year

2015, there is no consensus about the optimal CS

rate and appropriate interpretation of this

indicator remains a topic of debate.(2) More

recent efforts to determine the optimal C-section

rate also had limitations due to lack of external

validity and confounders.(2,3) The most common

complications associated with cesarean sections

are increased requirements of blood transfusions,

retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage,

prolonged hospital stays and increased changes of

maternal morbidity and mortality. (4, 5) Rising

trends in C-section rates are feared to implicate

lower threshold of labour pains maternal requests,

labour induction without indications and lesser

levels of expertise adopting instrumental

deliveries.(6-8)

There are several

reasons which explain variations in institutional

rates of C-section. These include the inherent

differences in patient characteristics, type of

institution and available resources. In addition,

institutional differences in obstetric practice

and pregnancy and labor management protocols can

account for this variation. (6) Therefore,

population-based C-section rates should not be

considered as recommended targets at facility

level. Indeed, systems designed to monitor

cesarean section rates at facilities should

consider these differences. C-section rates should

no longer be thought of being too high or too low

but rather whether they are appropriate. Thus,

C-section should only be conducted based on

medical indications, and efforts should be

directed towards improving access to all women in

need rather than striving to achieve an arbitrary

rate.(6,7) Therefore, policymakers, program

managers, clinicians, and administrators need a

standardized and internationally accepted

classification system to monitor and compare

C-section rates in a meaningful, reliable, and

action-oriented manner. (8) A systematic review of

existing C-section classification system conducted

in 2011 identified 27 different classification

systems of which Robson’s Ten Group Classification

System (RTGCS) was found to be the best

option.(5-6, 9) Vaginal Birth After Cesarean

(VBAC) is a safe alternative to repeat cesarean

section for both mother and infant. The major risk

of trial of labour is uterine rupture and possible

hysterectomy can be reduced by careful patient

selection. The Royal college of obstetricians and

gynecologists recommends the routine use of VBAC

checklist during antenatal counseling as they

would ensure informed consent and shared decision

making in women undergoing VBAC.(10-12) WHO

proposed Robson’s Ten Group Classification System

to monitor and compare the rates of C-section

between different health institutions in a

reliable and action-oriented manner there are many

studies that have shown a small reduction in

C-section rates following implementation of

Robson’s Classification system (Table 1).

The objective of

the current study was to audit C-section rate

using Robson’s Ten Group Classification System in

our tertiary care hospital, and to identify the

main contributors of each subgroup to overall

C-section rate.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a

cross-sectional study conducted at out tertiary

care center, Karpaga Vinayaga Institute of Medical

Sciences and Research Centre (KIMS&RC),

Madhuranthagam, Tamil Nadu, India during the

period of January 2019 to December 2021. The study

was conducted by reviewing the hospital record for

analyzing the C-sections performed during the

above-mentioned period. The study population

include the pregnant women who underwent

C-sections in our hospital during the specified

period. Study was approved by the Institutional

Ethical committee of KIMS&RC after the

approval from Scientific Advisory Committee.

Sample size was calculated based on the study done

by Radhakrishnan T et al on “increasing trend of

caesarean rates in India: evidence from NHFS 4”

which showed prevalence of caesarean section rates

of Tamil Nadu as 34%. (13)

Inclusion Criteria: The study

population included all women who gave birth from

January 2019 to December 2021.

Exclusion

Criteria: Laparotomy done for uterine

rupture and deliveries before fetal viability were

excluded from the study. Case sheets with missing

information were also excluded from the study.

Viability is considered after gestational age of

28 weeks or birth weight ≥ 1,000g, if gestational

age is unknown. (14, 15)

Information

regarding each C-section case was obtained from

hospital records of Medical records Department.

Using the medical registration number, we accessed

all C-sections performed during the study period

and all the required details of each case was

noted (Age, Parity, Gestational age, fetal

presentation, previous deliveries, onset of

labour, mode of delivery, birth weight etc.).

Distribution of all cesarean deliveries was then

categorized as per Robson’s Ten Group

Classification System (Table 1).(5,6, 8) The

C-section rate in percentage of total delivery and

contribution of each group to overall C-section

rate was calculated.

|

Table 1: Robson

ten group delivery classification system

|

|

Groups

|

Description

|

|

Group 1

|

Nulliparous,

singleton, cephalic, term spontaneous

labor.

|

|

Group 2

|

Nulliparous,

singleton, cephalic, term, induced labor

or C-SECTION before labor.

2a- Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥ 37

weeks’ gestation, induced labor.

2b- Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥ 37

weeks’ gestation, cesarean section before

labor.

|

|

Group 3

|

Multiparous

(excluding previous cesarean section),

singleton, cephalic, ≥ 37 weeks’

gestation, in spontaneous labor.

|

|

Group 4

|

Multiparous

without a previous uterine scar, with

singleton, cephalic pregnancy, ≥ 37 weeks’

gestation, induced or cesarean section

before labor.

4a- Multiparous without a previous uterine

scar, with singleton, cephalic pregnancy,

≥ 37 weeks’ gestation, induced labor.

4b- Multiparous without a previous uterine

scar, with singleton, cephalic pregnancy,

≥ 37 weeks’ gestation, cesarean section

before labor.

|

|

Group 5

|

Multiparous,

Singleton, Cephalic, term with a previous

C-section.

|

|

Group 6

|

Nulliparous,

Singleton, breech.

|

|

Group 7

|

All

multiparous with a single breech

(including previous cesarean section).

|

|

Group 8

|

Multiple

pregnancies.

|

|

Group 9

|

Singleton

pregnancy in transverse or oblique lie.

|

|

Group 10

|

Singleton,

cephalic, preterm pregnancies (including

previous cesarean section).

|

The overall

caesarean section rate was calculated, and the

major contributing factor was also identified. The

contribution of each group to caesarean section

rate was calculated.

Statistical

Analysis: All the data was recorded in an

excel sheet and exported for analysis using IBM

SPSS, version 16.0 (IBM Corp., USA). The overall

C-section rate at the institution was calculated

first. We coded all abstracted data and women were

categorized into one of the ten Robson groups. For

each group, size relative to the entire obstetric

population, contribution to the overall C-section

rate, and C-section rate within the group were

calculated.

Results

The total number of

women meeting the inclusion criteria and delivered

during the period of study were 401. The overall

caesarean section rate during the period of study

was 46%. The 401 antenatal mothers who underwent

C-section were in the age range of 18 to 38 years

and maximum number of women were aged between

21-30 years (68%). The mean age of participants

was 25.4 ± 5.2 years.

Of the overall 401

antenatal women who has C-section 46% were

primigravida and rest were multigravida (54%). The

401 women who underwent C-section, 93% were term

patients and 7% were pre-term. In the study 99%

women presented with singleton pregnancies and 1%

with multiple pregnancies (Table 2).

|

Table 2:

Baseline characteristics of the study

population

|

|

Parameter

|

No. of Cases

|

Percentage

|

|

Parity

|

|

|

|

Primigravida

|

185

|

46%

|

|

Multigravida

|

216

|

54%

|

|

Gestational age

|

|

Pre-term

|

28

|

7%

|

|

Term

|

373

|

93%

|

|

No. of foetus

|

|

Single

|

397

|

99%

|

|

Multiple

|

4

|

1%

|

|

Onset of labour

|

|

Emergency

|

298

|

15%

|

|

Elective

|

132

|

33%

|

|

Fetal Presentation

|

|

Cephalic

|

382

|

95%

|

|

Breech

|

15

|

4%

|

|

Transverse/Oblique Lie

|

4

|

1%

|

|

Birth Weight

|

|

<2500

|

68

|

17%

|

|

2500–4000

|

307

|

77%

|

|

>4000

|

26

|

6%

|

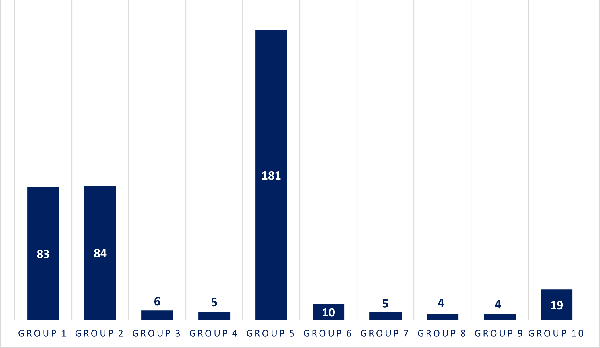

The 401 women who

underwent C-section were classified in RTGCS, 45%

women in Group 5 and it contributed to the maximum

number of the total C-section rates. The second

highest contributor was Group 1 and Group 2

contributing to 41% of the overall C-section

rates. Other groups who underwent C-section,

mentioned in the Table 3 and Figure 1.

|

Table 3:

Classification of studied population as

per Robson Ten Group Classification

System

|

|

Robson TGCS

|

Percentage of antenatal women

|

|

Group 1

|

21%

|

|

Group 2

|

21%

|

|

Group 3

|

1%

|

|

Group 4

|

1%

|

|

Group 5

|

45%

|

|

Group 6

|

2%

|

|

Group 7

|

1%

|

|

Group 8

|

1%

|

|

Group 9

|

1%

|

|

Group 10

|

5%

|

|

| Figure

1: Shows the no. of antenatal

women as per Robson Ten Group

Classification System |

Out of 401 women

analyzed, 298 were emergency LSCS (74%) and 103

were elective LSCS (26%). 95% patients who

underwent caesarean section had no complications

and 5% of patients had complications like

postpartum hemorrhage, blood transfusion and

postpartum eclampsia. Totally 407 live babies were

delivered including twin births. Maximum number of

babies weighed between 2500 gm - 4000 gm (77%)

(Table 2). The commonest cause for NICU admission

was preterm birth. Other causes were distress at

birth and grunting.

Discussion

C-section is a key

intervention used to decrease maternal and

neonatal morbidity and mortality. (4-6) Despite

its proven benefits, complications such as

infection, bleeding, anesthetic accidents and even

death are associated with C-section. Further,

future pregnancies can be complicated by

spontaneous preterm birth, uterine rupture, and

abnormal placentation.(16,17) The Robson ten group

classification system enables institution-specific

monitoring and auditing and can be a powerful tool

to inform practice across different settings.

(6-8) In the present study RTGCS was used for

assessing the proportion of each group in the

obstetric population, the contribution of

C-section in each group to the overall C-section

rate. The present study includes 401 mothers who

underwent C-section. Among all the groups as per

Robson’s TGCS classification, Group 5 contributed

to the maximum C-section rates followed by Group 1

and Group 2. This indicates high C-section rate

both in primary (groups 1 and 2) and secondary

(group 5) C-sections. Our study findings are

similar to the study done by Ray A et al and

Abubeker FA et al in Ethiopia, the overall

C-section rate was 28.9% and 30.8% respectively

and Group 10, group 2 and group 5 contributed to

maximum to caesarean section rates, 19.1%, 18.3%

and 17.1% respectively of the overall C-section

rates. (18, 19) Similarly, our study findings are

in line with a study done in India where Group 1,

Group 2 and Group 5 contributed to 19% and 18% of

all deliveries respectively.(20,21)

Cesarean section

performed at a rate higher than 10-15% in absence

of a clinical justification do not reduce maternal

or infant mortality rates. A study performed in

China, the maternal morbidity and mortality were

lower following VBAC compared with repeated

cesareans, but the opposite was seen among

Canadian women. Many hospital-based studies adapt

Robson’s TGCS for monitoring C-section rates the

group 5 is the major contributor to overall

C-section rates and found to be the high-risk

group by several studies which is also seen in the

present study. Mittal et al., reported the

C-section trend using Robson classification in

north India to assess the trend of C-section rate

for 3 years and should a static rate of C-section

in each group over the years.(20) In the study

conducted by Kacerauskiene at al reaudit of

cesarean deliveries should a significant reduction

in overall C-section rate from 26.9% in 2012 to

22.7% in 2014(P<0.001).(21) Study by Ray at al

has found that women with previous C-section

contributes maximum to overall C-section rates

followed by term nulliparous who are induced or

underwent C-section before labour.(20) In a

Canadian study using Robson’s classification most

of the obstetric population attributed to group

6(36.6%) and groups 2 and 1 ranked as second and

third largest contributors (15.7 and 14.1%

respectively).

Several studies

across different settings identified Group 5 as

the leading contributor to the C-section

rate.(13,14,16) In our study, Group 5 was the

largest contributor to the overall C-section rate.

These findings are suggestive of moderately high

C-section rate.(7) which need attention. Though

the safety and long-term benefits of vaginal birth

after cesarean (VBAC) are well established, 45% of

women in Group 5 underwent repeat C-section (Table

3). Thus, there is a need to evaluate the

proportion of women who were offered a trial of

labor and the success rate of VBAC. This will

enable the design and implementation of antenatal

counseling strategies and labor management

protocols, reducing the number of repeat

C-section.

The limitations of

this study, as such are the limitations of

Robson’s ten group classification system. It does

not classify caesarean sections done for specific

conditions like major degree placenta previa and

those done for maternal request. It also does not

classify caesarean sections done for medical,

other obstetric complication in the mother and

those C-section done for fetal indications E.g:

Anhydramnios. As the present study has audited

only indications for C-section, it was unable to

analyse the total number women in that group and

the overall percentage of women in that group

requiring C-section versus those who had vaginal

delivery which would have added more meaning to

the audit.

Conclusion

Robson’s TGCS

server as an important tool for auditing C-section

and can easily implemented at institutional levels

for comparison of C-section rates. As fetal

distress is one among the common indication for

primary caesarean section and electronic fetal

monitoring is the norm, it is important that all

obstetricians in the institute are well trained in

interpreting of cardiotocography (CTG). The

residents must be well trained in procedures like

external cephalic version, assisted breech

delivery and operative vaginal delivery efforts to

reduce overall C-section rate should focus on

reducing primary C-section rate and increasing

VBAC.

Acknowledgement

The authors would

like to acknowledge the medical record section of

KIMS&RC for allowing to access the case record

files. Authors would like to thank Trustee,

Managing Director Dr.R. Annamalai M.S.,M.Ch., for

his support in accomplishing this project.

References

- World Health Organization. Appropriate

technology for birth. Lancet

1985;2: 436–437.

- World Health Organization. Human Reproduction

Programme, 10 April 2015. WHO statement on

caesarean section rates. Reprod Health

Matters 2015; 23:149–150.

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, et al. The

increasing trend in caesarean section rates:

global, regional and national estimates:

1990-2014. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0148343.

- Ye J, Zhang J, Mikolajczyk R, et al.

Association between rates of caesarean section

and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st

century: a worldwide population-based ecological

study with longitudinal data. BJOG

2016; 123:745–753.

- Robson M, Hartigan L, Murphy M. Methods of

achieving and maintaining an appropriate

caesarean section rate. Best Pract Res

Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

2013;27(2):297–308.

- Robson MS. Classification of caesarean

sections. Fetal Matern Med Rev

2001;12(1):23–39.

- Torloni MR, Betran AP, Souza JP, Widmer M,

Allen T, Gulmezoglu M, Merialdi M.

Classifications for cesarean section: a

systematic review. PLoS One 2011;

6(1):e14566.

- Dhodapkar SB, Bhairavi S, Daniel M, Chauhan

NS, Chauhan RC. Analysis of caesarean sections

according to Robson’s ten group classification

system at a tertiary care teaching hospital in

South India. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet

Gynecol 2017;4(3):745-749.

- Tanaka K, Mahomed K. The ten-group Robson

classification: a single centre approach

identifying strategies to optimise caesarean

section rates. Obstet Gynecol Int.

2017;2017: 5648938. doi: 10.1155/2017/5648938.

- Harrison MS, Pasha O, Saleem S, Ali S, Chomba

E, Carlo WA, Garces AL, Krebs NF, Hambidge KM,

Goudar SS. A prospective study of maternal,

fetal and neonatal outcomes in the setting of

cesarean section in low-and middle‐income

countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

2017;96(4):410–420.

- Costa ML, Cecatti JG, Souza JP, Milanez HM,

Gulmezoglu MA. Using a Caesarean Section

Classification System based on characteristics

of the population as a way of monitoring

obstetric practice. Reprod Health

2010; 26(7): 13. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-7-13.

- Litorp H, Kidanto HL, Nystrom L, Darj E, Essen

B. Increasing caesarean section rates among

low-risk groups: a panel study classifying

deliveries according to Robson at a university

hospital in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy

Childbirth 2013;13:107.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-107.

- Radhakrishnan T, Vasanthakumari KP, Babu PK.

Increasing trend of caesarean rates in India:

evidence from NFHS-4. Journal of Medical

Science and Clinical Research

2017;5(8):26167-26176.

- Triunfo S, Ferrazzani S, Lanzone A, Scambia G.

Identification of obstetric targets for reducing

cesarean section rate using the Robson Ten Group

Classification in a tertiary level hospital.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

2015;189:91–95.doi:

10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.03.030.

- Sah S, Goel R, Goel JK. Analysis of caesarean

section rate according to Robson’s criteria in

tertiary care centre. International

Journal of Reproduction Contraception

Obstetrics Gynecology

2018;7(8):3060–3064.

- Mittal P, Pandey D, Suri J, Bharti R. Trend

prediction for cesarean deliveries based on

Robson classification system at a tertiary

referral unit of north India. J Obstet

Gynecol India. 2020;70(2):111-118.

- Kacerauskiene J, Bartusevicience E, Railaite

DR,et al. Implementation of the Robson

classification in clinical practice: Lithuania’s

experience. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

2017;17:432.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1625-9

- Ray A, Jose S.Analysis of cesarean section

according to Robson’s ten group classification

system and evaluating the indications within the

groups. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet

Gynecol 2017;6(2):447-451.

- Abubeker FA, Gashawbeza B, Gebre TM,

Wondafrash M et al. Analysis of cesarean section

rates using Robson ten group classification

system in a tertiary teaching hospital, Addis

Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC

Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:767.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03474-x.

- Tura AK, Pijpers O, de Man M, et al. Analysis

of caesarean sections using Robson 10-group

classification system in a university hospital

in eastern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMJ

Open 2018;8(4):e020520. doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2017-020520.

- Jose J, Arumugam SC, Habeebullah S. An audit

of caesarean section rate based on Robson’s ten

group classification system. Int J Reprod

Contracept Obstet Gynecol

2020;9:2803-2807.

|