|

Introduction

Adolescence

is a period of psychological and somatic growth

and development that spans between the ages of 10

and 19 [1,2]. Adolescent pregnancy and childbirth

remain a public health problem [2,3], with medical

and cognitive risks associated with biological

immaturity, the social determinants of health and

the quality of the healthcare system [3,4]. These

risks include poor attendance at antenatal clinics

[3,5], prematurity [5,6], obstructed labour [7],

vaginal tears , puerperal psychosis [8],

pre-eclampsia and eclampsia [9], low birth weight

[9] and high neonatal mortality [10]. Rural areas

are more vulnerable than urban areas [4].

Caesarean section is the surgical intervention

that is constantly on the increase, especially in

urban areas [11–13], with rates ranging from 5.0%

to 42.8% [14], [15]. In Africa, the frequency of

caesarean section varies from 5.0% to 37.5% and

6.6% among adolescents [11,14,16]. There are

regional differences [15]. The main indications,

in all age groups, are maternal and foetal. The

impact on maternal and neonatal mortality is not

negligible, especially in Africa [17,18]. Age

under twenty favours caesarean section due to

fetal-pelvic disproportion [2,11,19]. For Ymelle et

al. [18] in Cameroon, caesarean sections in

adolescents represent 6.9%. Eouni et al.

[1] report 44% caesarean sections among teenage

deliveries in the Republic of Congo. In the

Democratic Republic of Congo, 11.7% of caesareans

in the town of Mbuji-Mayi were adolescents [20],

and the study conducted in the rural area of Moba

reported 48 cases of caesarean section among 523

deliveries of adolescents, i.e. 9.2% [2].

The aim of this

study is to determine the prevalence, indications,

evolution and factors associated with the risk of

caesarean section among adolescent in rural Lubao,

in the central-eastern Democratic Republic of

Congo. A comparison with adult women will enable

factors associated with the risk of caesarean

section to be determined.

Methods

Setting

This study was

conducted at the Lubao general referral hospital,

Lubao health zone and territory, Lomami province,

central Democratic Republic of Congo. The

territory of Lubao has three rural health zones

(Kamana, Tshofa and Lubao), each of which has a

general referral hospital, with no specialist

gynaecology and obstetrics doctor.

Type and

period of study

This was a

cross-sectional, analytical study with data

covering the period 2018 to 2022. The data were

collected by KoboCollect from the maternity ward

and operating theatre registers.

Inclusion criteria and sampling

For this study, we

included all deliveries during the data collection

period.

Data

collection

Data relating to

adolescents were obtained from partograms,

delivery registers and surgical operations

(caesarean sections). In some cases, operative

protocols were reviewed to complete the data on

vaginal deliveries. A KoboCollect data collection

form prepared in advance was used to collect the

variables sought on the adolescent girls and adult

women targeted by this study.

Operational definitions

Adolescent:

According to the WHO, this is a girl during the

age period between 10 and 19, i.e. less than

twenty years old.

Teenage

pregnancy: This is pregnancy that

occurs between the ages of 13 and 19.

Parameters

studied

a) Independent variable: Age

(years)

b)

Dependent variable: Frequency of

adolescent deliveries (by year of study),

occupation, level of education, marital status,

history of caesarean section, number of times

scarred uterus, parity, gestational age, modes of

delivery (vaginal and vaginal), type of pregnancy

(singleton and multiple), indication for caesarean

section, mode of admission (referred and

non-referred), types of caesarean section

(scheduled and urgent), fetal presentation

(breech, cephalic, transverse), onset of labour

(artificial, spontaneous), maternal outcome (good,

bad, death), outcome of the newborn during the

maternal early neonatal period (good, bad, death).

Data processing and

statistical analysis

The data collected

by KoboCollect during the study period were

downloaded onto an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft,

USA, 2010) and imported for processing into

Epi-Info 7.1 (Center for Disease Control and

Prevention, Atlanta, USA, 2011) [21] and Jamovi

2.3.21 [22]. The results were presented in the

form of tables and graphs (Figures) including

numbers, proportions expressed as a percentage and

indicators of location (central tendencies: mean,

extremes, median) and dispersion (interquartile

range and standard deviation). The relationship

between the various parameters studied was

established using the p-value and the odd ratio at

the significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Ethics

The data for this

study were collected in strict compliance with

confidentiality and protocol. Authorisation had

been obtained from the authorities managing the

two health entities targeted by our study.

Results

From 2018 to 2022,

2,444 deliveries were recorded at the Lubao

general referral hospital, including 375 caesarean

sections, or 15.3%. Among adolescent girls, 64

caesarean sections were performed out of 82

deliveries (78.0%), while adult women recorded

only 311 caesarean sections out of 2,362

deliveries (13.2%). The difference observed was

highly statistically significant (OR 23.44 [CI95%

13.71-40.09]; p=0.0000) (Figure 1).

|

Figure

1: Delivery routes at Lubao General

Referral Hospital

(p=0.0000; OR 23.448; IC95% 13.71-40.09) |

The typical profile

of the adolescent and adult woman shows that the

age varies from 15 to 19 years Vs 20 to 48 years,

with a median of 18 ± 0.25 years Vs 30 ± 12.5

years; student (n=43 i.e. 67.2% Vs n=6 i.e. 1.9%)

or farmer (n=19 i.e. 29.7% Vs n=160 i.e. 51.4%);

secondary education (n=62 or 96.9% Vs n=266 or

85.5%); married (n=50 or 78.1% Vs n=309 or 99.4%);

located less than six kilometers from the general

referral hospital (n=36 or 56.2% Vs n=194 or

62.4%). The differences observed between the two

groups were statistically significant for

occupation (p=0.0000), level of education

(p=0.0139) and marital status (p=0.0000) (Tables 1

and 3). There was no difference in the distance

travelled from home to the general referral

hospital (p=0.40803): the average was 9.95 ± 9.72

kilometers for adolescent girls and 8.3 ± 8.6

kilometers for adult women (Table 3).

|

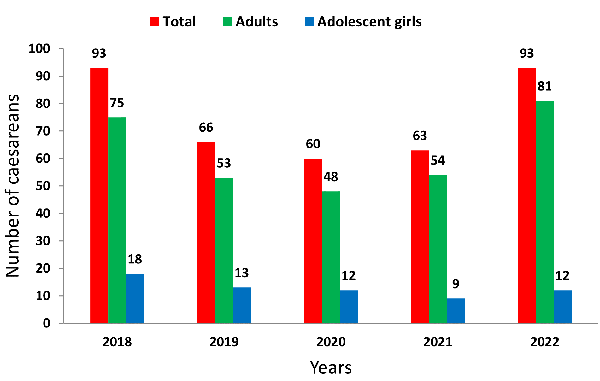

| Figure

2: Annual evolution of caesareans

|

Fetal macrosomia

(n=36; 56.3%), acute fetal distress (n=15; 23.4%)

and bony dystocia (n=7; 10.9%) were the main

indications for caesarean section among adolescent

women. Adult women in Lubao had fetal macrosomia

(n=86; 27.7%), acute fetal distress (n=78; 25.1%)

and placenta praevia (n=61; 19.6%) as the main

indications for caesarean section.

Mechanical dystocia

were predominantly encountered among adolescent

women, compared with dynamic dystocia in the group

of adult women. The difference observed was

statistically significant (OR 2.08 [IC95%

1.11-3.87]; p=0.0190) (Tables 2 and 4).

The maternal

outcome of caesareans was characterized by five

deaths (1.3%) and 14 poor outcomes (3.7%),

compared with 365 good outcomes (94.9%). Among

adolescents and adult women: one death (1.6%) Vs.

4 deaths (1.3%), three poor outcomes (4.7%) Vs 11

(3.5%) and 60 good outcomes (93.7%) Vs. 296

(95.2%). The difference observed was not

statistically significant (OR 1.31 (IC95%

0.42-4.10); p=0.6355). (Figure 3a)

In the early

neonatal period, there were 49 deaths, 64 poor

outcomes and 277 good outcomes among the 390

newborns (360 singleton pregnancies and 15 twin

pregnancies). For adolescents and adult women

respectively: 9 deaths (14%) vs. 40 (12.9%), 6

poor outcomes (9.4%) vs. 58 (18.6%) and 49 good

outcomes (76.6%) vs. 228 (73.3). The difference

observed was not statistically significant (OR

1.40 (IC95% 0.75-2.62); p=0.3589). (Figure 3b).

Level of education did not influence maternal

outcome [OR 0.276 (95% CI 0.09-0.81); p=0.0136].

| Table

1: Sociodemographic characteristics

|

|

Characteristics

|

Total

|

Adolescents

|

Adults

|

p-value

|

|

Age (Years)

|

|

10-19

|

64 (17.1)

|

64 (100)

|

0

|

|

|

20 and over

|

311 (82.9)

|

0

|

311 (100)

|

0.0000

|

|

Extremes

|

15-48

|

15-19

|

20-48

|

|

|

Median + Interquartile

|

27 ±14.5

|

18 ± 0.25

|

30±12.5

|

|

|

Profession

|

|

None

|

120 (32.0)

|

1 (1.6)

|

119 (38.3)

|

|

|

Farmer

|

179 (47.7)

|

19 (29.7)

|

160 (51.4)

|

|

|

Pupil

|

49 (13.1)

|

43 (67.2)

|

6 (1.9)

|

0.0000

|

|

Trader

|

22 (5.9)

|

1 (1.6)

|

21 (6.8)

|

|

|

State public agent

|

5 (1.3)

|

0

|

5 (1.6)

|

|

|

Studies

|

|

Primary

|

36 (9.6)

|

1 (1.6)

|

35 (11.3)

|

|

|

Secondary

|

328 (87.5)

|

62 (96.9)

|

266 (85.5)

|

|

|

Higher and university studies

|

10 (2.7)

|

0

|

10 (3.2)

|

0.0139

|

|

Informal training

|

1 (0.3)

|

1 (1.6)

|

0

|

|

|

Marital status

|

|

Single

|

16 (4.3)

|

14 (21.9)

|

2 (0.6)

|

0.0000

|

|

Married

|

359 (95.7)

|

50 (78.1)

|

309 (99.4)

|

|

|

Distance from home to Hospital

|

|

≤ 5 Km

|

230 (61.3)

|

36 (56.2)

|

194 (62.4)

|

|

|

6 – 10 Km

|

16 (4.3)

|

3 (4.7)

|

13 (4.2)

|

0.40803

|

|

11 and over

|

129 (34.4)

|

25 (39.1)

|

104 (33.4)

|

|

|

Means + SD

|

|

9.95 ± 9.72

|

8.3 ± 8.6

|

|

|

Median + Interquartile

|

|

5.0 ± 16.8

|

4 ± 12

|

|

|

Extremes

|

1-40

|

1-38

|

1-40

|

|

| Table 2: Indications

for caesareans |

|

Indications

|

Total

|

Adolescents

|

Adults

|

|

Excess of term

|

5 (1.3)

|

0

|

5 (1.6)

|

|

Dystocia of presentation

|

20 (5.3)

|

3 (4.7)

|

17 (5.5)

|

|

Bone dystocia (borderline, shrunken

pelvis)

|

7 (1.9)

|

7 (10.9)

|

0

|

|

Failed uterine test (Dynamic dystocia)

|

18 (4.8)

|

0

|

18 (5.8)

|

|

Multiple pregnancy

|

15 (4.0)

|

0

|

15 (4.8)

|

|

Precious pregnancy

|

5 (1.3)

|

0

|

5 (1.6)

|

|

Fetal macrosomia

|

122 (32.5)

|

36 (56.3)

|

86 (27.7)

|

|

Placenta previa

|

61 (16.3)

|

0

|

61 (19.6)

|

|

Uterine rupture

|

4 (1.1)

|

1 (1.6)

|

3 (1.0)

|

|

Acute fetal distress

|

93 (24.8)

|

15 (23.4)

|

78 (25.1)

|

|

Scarred uterus

|

25 (6.7)

|

2 (3.1)

|

23 (7.4)

|

| Table 3: Obstetric

characteristics |

|

Characteristics

|

Total

|

Adolescents

|

Adults

|

p-value

|

|

Antecedents de caesarean

|

|

No

|

338 (90.1)

|

62 (96.9)

|

276 (88.7)

|

|

|

Yes

|

37 (9.9)

|

2 (3.1)

|

35 (11.3)

|

0.04704

|

|

Scarred uterus

|

|

No

|

338 (90.1)

|

62 (96.9)

|

276 (88.7)

|

|

|

Once

|

31 (8.3)

|

2 (3.1)

|

29 (9.3)

|

|

|

Twice

|

6 (1.6)

|

0

|

6 (1.9)

|

|

|

Gestational age (WA)

|

|

31-36

|

19 (5.1)

|

62 (96.9)

|

17 (5.5)

|

|

|

37-42

|

347 (92.5)

|

2 (3.1)

|

285 (91.6)

|

|

|

43 and over

|

9 (2.4)

|

0

|

9 (2.9)

|

|

|

Extremes

|

33 - 44

|

34 - 40

|

33 - 44

|

|

|

Means + SD

|

|

37. 6 ± 1.1

|

|

|

|

Median

|

|

37.0 ± 1.0

|

|

|

|

Parity

|

|

Nulliparous

|

114 (30.4)

|

46 (71.9)

|

68 (21.9)

|

|

|

Primiparous

|

94 (25.1)

|

18 (28.1)

|

76 (24.4)

|

0.0000

|

|

Pauciparous

|

87 (23.2)

|

0

|

87 (28.0)

|

|

|

Multipara

|

34 (9.1)

|

0

|

34 (10.9)

|

|

|

Grand multiparous

|

22 (5.9)

|

0

|

22 (7.1)

|

|

|

Types of pregnancy

|

|

Mono-fetale

|

360 (96.0)

|

64 (100)

|

296 (95.2)

|

0.149

|

|

Multifetale (twin)

|

15 (4.0)

|

0

|

15 (4.8)

|

|

|

Types of caesarean

|

|

Scheduled (elective)

|

13 (3.5)

|

1 (1.6)

|

12 (3.9)

|

0.5897

|

|

Urgent

|

362 (96.5)

|

63 (98.4)

|

299 (96.1)

|

|

|

Mode of admission

|

|

Refereed

|

240 (64.0)

|

39 (60.9)

|

201 (64.6)

|

0.5751

|

|

Not refereed

|

135 (36.0)

|

25 (39.1)

|

110 (35.4)

|

|

|

Beginning labor

|

|

Spontaneous

|

345 (92.0)

|

62 (96.9)

|

283 (91.0)

|

|

|

Artificial

|

30 (8.0)

|

2 (3.1)

|

28 (9.0)

|

0.114

|

|

Fetal presentation

|

|

Cephalic

|

348 (92.8)

|

59 (92.2)

|

289 (92.9)

|

|

|

Seat

|

15 (4.0)

|

3 (4.7)

|

12 (3.9)

|

0.968

|

|

Transverse

|

12 (3.2)

|

2 (3.1)

|

10 (3.2)

|

|

|

|

| Figure

3: Mothers (a) and new-born (b) evolutions

|

| Table 4:

Multivariate Analysis |

|

Characteristics

|

Total

|

Adolescents

|

Adults

|

OR

|

IC95%

|

p-value

|

|

Profession

|

|

Yes

|

255 (68.0)

|

63 (98.4)

|

192 (61.7)

|

39.04

|

5.34-285.27

|

0.0000*

|

|

Not

|

120 (32.0)

|

1 (1.6)

|

119 (38.3)

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary and over Studies

|

|

Yes

|

338 (90.1)

|

62 (96.9)

|

276 (88.8)

|

3.93

|

0.92-16.78

|

0.0477*

|

|

Not

|

37 (9.9)

|

2 (3.1)

|

35 (11.2)

|

|

|

|

|

Marital status

|

|

Single

|

16 (4.3)

|

14 (21.9)

|

2 (0.6)

|

43.26

|

9.54-196.10

|

0.0000*

|

|

Married

|

359 (95.7)

|

50 (78.1)

|

309 (99.4)

|

|

|

|

|

Distance: home to Hospital

|

|

≤ 10 Km

|

246 (65.6)

|

39 (60.9)

|

207 (66.6)

|

0.78

|

0.45-1.36

|

0.3887

|

|

11 and over Km

|

129 (34.4)

|

25 (39.1)

|

104 (33.4)

|

|

|

|

|

Antecedents of caesarean

|

|

No

|

338 (90.1)

|

62 (96.9)

|

276 (88.7)

|

3.93

|

0.92-16,78

|

0.0470*

|

|

Yes

|

37 (9.9)

|

2 (3.1)

|

35 (11.3)

|

|

|

|

|

Scarred uterus

|

|

Yes

|

36 (9.6)

|

2 (3.1)

|

34 (11.0)

|

0.26

|

0.06-1.11

|

0.0527

|

|

Not

|

338 (90.4)

|

62 (96.9)

|

276 (89.0)

|

|

|

|

|

Gestational age (WA)

|

|

31-36

|

19 (5.1)

|

2 (3.1)

|

17 (5.5)

|

0.55

|

0.08-2.47

|

0.4367

|

|

37-44

|

356 (94.9)

|

62 (96.9)

|

294 (94.5)

|

|

|

|

|

Parity ≤ 3

|

|

Yes

|

295 (78.7)

|

64 (100)

|

231 (74.3)

|

|

|

0.0000*

|

|

Not

|

80 (21.3)

|

0

|

80 (25.7)

|

|

|

|

|

Types of pregnancy

|

|

Mono-fetale

|

360 (96.0)

|

64 (100)

|

296 (95.2)

|

|

|

0.0729

|

|

Multifetale (twin)

|

15 (4.0)

|

0

|

15 (4.8)

|

|

|

|

|

Type of caesarean

|

|

Scheduled (elective)

|

13 (3.5)

|

1 (1.6)

|

12 (3.9)

|

0.39

|

0.05-3.09

|

0.360

|

|

Urgent

|

362 (96.5)

|

63 (98.4)

|

299 (96.1)

|

|

|

|

|

Mode of admission

|

|

Refereed

|

240 (64.0)

|

39 (60.9)

|

201 (64.6)

|

1.17

|

0.67-2.03

|

0.575

|

|

Not refereed

|

135 (36.0)

|

25 (39.1)

|

110 (35.4)

|

|

|

|

|

Beginning labor

|

|

Spontaneous

|

345 (92.0)

|

62 (96.9)

|

283 (91.0)

|

0.32

|

0.07-1.40

|

0.1144

|

|

Artificial

|

30 (8.0)

|

2 (3.1)

|

28 (9.0)

|

|

|

|

|

Fetal presentation

|

|

Cephalic

|

348 (92.8)

|

59 (92.2)

|

289 (92.9)

|

0.89

|

0.32-2.46

|

0.8351

|

|

No cephalic

|

27 (7.2)

|

5 (7.8)

|

22 (7.1)

|

|

|

|

|

Mechanical dystocia

|

|

Yes

|

239 (63.7)

|

49 (76.6)

|

190 (61.1)

|

2.08

|

1.11-3.87

|

0.0190*

|

|

Not

|

136 (36.3)

|

15 (23.4)

|

121 (38.9)

|

|

|

|

Discussion

Prevalence

of caesarean sections among adolescents

The persistent high

incidence of maternal deaths remains a challenge

for Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

It is estimated that one woman in 42 is at risk of

maternal death, and 70% of maternal deaths are

attributable to Africa [15,23,24]. Preventable

causes, including those related to childbirth,

have been identified as the main causes of

maternal death [23].

Adolescent

childbirth spares no region of the World Health

Organisation [13,25–27]. In this series of

studies, we made a comparison with adult women in

order to determine the proportion of caesarean

sections in each group: the prevalence of

caesarean sections is scientifically higher among

adolescent girls than among adult women. These

results confirm what has been reported in the

medical literature in Guatemala, India, Kenya,

Pakistan, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of

Congo [26]. In Mbuji-Mayi, Claire et al. [20]

reported 11.7% of caesarean sections and John et

al. [28] 13.5% of caesarean sections among

adolescents, which is close to our results: 3.4%

of deliveries and 17.1% of caesarean sections. It

should be noted, however, that in studies on

caesarean section where the methodology does not

include a control group of adult women, there is a

risk of using the numbers of the majority of women

giving birth as a basis for wrongly concluding

that adult women present a higher risk of

caesarean section than adolescent women.

Precaution was used to avoid this risk of

interpretation bias.

Adolescents present

the risk associated with biological immaturity, as

demonstrated by the high risk of fetal-pelvic

disproportion and the numerous cases of

consequences associated with obstetric

inexperience [1,27].

Indications for caesarean section

The main indications

for caesarean section vary from region to region

[15]. In our study, caesarean sections were

significantly indicated for mechanical and

emergency dystocia. This may reflect the poor

quality of antenatal consultations. Fetal

macrosomia, acute fetal distress and bony dystocia

(found only among adolescents) are the main

indications for caesarean section among the

adolescents studied. These results are similar to

those reported by Adelaiye et al. [29]

except that pre-eclampsia/eclampsia replaces

macrosomia in first place. This predominance of

foetal macrosomia in adolescent and adult women

needs to be assessed. We are concerned about

diagnostic errors and recommend prospective and

KAP (knowledge, attitudes and practices) studies.

The majority of

studies on caesarean sections do not take controls

into account [7], [30], [31]. Comparative studies

of caesarean sections between adolescent and adult

women are still rare. We have not found a single

study conducted in our area (province) or in the

Democratic Republic of Congo.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes

Childbirth among

adolescents must be carefully monitored because of

the risks identified in the literature [7], [8],

[32], [33]. These risks can lead to maternal and

newborn deaths. In this study, overall maternal

mortality was 13‰ (five women) and early neonatal

mortality was 13.6% (49 newborns). It was found

that there was no statistical difference between

adolescent and adult women regarding maternal and

neonatal outcomes. Health care staff must improve

the quality of care for all categories of women

undergoing caesarean section, as the proportions

of maternal and newborn deaths remain high.

Vasconcelos et al. [34]recommend low APGAR scores

and the performance of resuscitation manoeuvres as

unfavourable factors in the outcome of newborns

born to adolescent mothers. In a meta-analysis,

Amjad et al. [4] mention low level of education as

a factor determining the unfavourable outcome of

pregnancy among adolescents, which is contrary to

our results. In our context, more in-depth studies

(integrating factors such as neonatal

resuscitation, maternal anaemia, birth weight, and

neonatal infection) are absolutely necessary to

evaluate the maternal outcome of caesarean section

and neonatal outcome between adult and adolescent

women.

Conclusion

Maternal and

neonatal mortality and morbidity remain a concern

for healthcare professionals. Childbirth remains a

crucial period which, with quality care, could

reduce the high frequency of maternal deaths in

our environment. Pregnancy among minors is a

serious public health problem for adolescent

girls, despite the measures that have been put in

place to combat it. Teenage girls have a very high

risk of caesarean section compared with adult

women. The main indications are avoidable. Raising

parents' awareness of the risks of early marriage,

educating girls about sex education in schools,

churches and youth clubs, combating sexual

exploitation and abuse, and even sexual violence,

are all solutions that should be considered.

Maternity wards also need to be equipped with

neonatal resuscitation facilities to ensure that

newborn babies are properly cared for. Priority

should be given to incubators (of which there are

none in the maternity unit) for temperature

control.

This study opens up

the possibility of multicentre studies to assess

the impact of measures to combat the marriage of

under-age girls.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not declare any conflicts of

interest in connection with this study. This study

was funded by the authors' own contributions.

References

- Eouani LEM, Mokoko JC, Itoua C, Iloki LH.

Childbirth in the Adolescent Female at the

General Hospital of Loandjili (Congo).

Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

2018;8(12):1140–6.

- Kabemba BH, Alimasi YG, Ntambwe AM, Kalamba

ME, Kitenge FF, Nyongonyi OE, et al.

Adolescent Pregnancy and Delivery in the Rural

Areas of DR. Congo: A Cross-Sectional

Descriptive Study (2014 to 2016). Open

Access Library Journal. 2018;5(8).

- Amoadu M, Hagan D, Ansah EW. Adverse obstetric

and neonatal outcomes of adolescent pregnancies

in Africa: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy

Childbirth. 2022;27;22:598.

- Amjad S, MacDonald I, Chambers T,

Osornio-Vargas A, Chandra S, Voaklander D, et

al. Social determinants of health and adverse

maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent

pregnancies: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol.

2019;33(1):88–99.

- Uzunov AV, Secara DC, Constantin AE, Mehedintu

C, Cirstoiu MM. Difference between Preterm Birth

in Adolescent and Adult Patients. Maedica

(Bucur), 2022;17(4):789–94.

- Afulani PA, Altman M, Musana J, Sudhinaraset

M. Conceptualizing pathways linking women’s

empowerment and prematurity in developing

countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

2017 Nov 8;17(Suppl 2):338.

- Kabemba BH, Mongane TB, Kunda SK, Saturnin

LBJJ, Ayumba DL, Tube JK, et al.

Epidemiological Profile of Childbirth among

Primiparous Women in Rural Areas of Tanganyika

Province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Open

Access Library Journal. 2021;8(3):1–13.

- Poinso F, Samuellian JC, Delzenne V, Huiart L,

Sparrow JS, Rufo M. Dépressions du post-partum:

délimitation d’un groupe à haut risque dès la

maternité, évaluation prospective et relation

mère-bébé. La psychiatrie de l’enfant.

2001;44(2):379–413.

- Ngowa JDK, Kasia JM, Pisoh WD, Ngassam A, Noa

C. Obstetrical and Perinatal Outcomes of

Adolescent Pregnancies in Cameroon: A

Retrospective Cohort Study at the Yaoundé

General Hospital. Open Journal of Obstetrics

and Gynecology. 2015;5(2):88–93.

- Ochieng AM, Agardh A, Larsson M, Asamoah BO.

Survival patterns of neonates born to adolescent

mothers and the effect of pregnancy intentions

and marital status on newborn survival in Kenya,

Uganda, and Tanzania, 2014–2016. Glob

Health Action. 2022;15(1):1-17.

- Essiben F, Belinga E, Ndoua CN, Moukouri G,

Eman MM, Dohbit JS, et al. La

Césarienne en Milieu à Ressources Limitées :

Évolution de la Fréquence, des Indications et du

Pronostic à Dix Ans d’Intervalle. Health

Sci Dis. 2020;21(2). In

https://www.hsd-fmsb.org/index.php/hsd/article/view/1771

- Ganeriwal SA, Ryan GA, Purandare NC, Purandare

CN. Examining the role and relevance of the

critical analysis and comparison of cesarean

section rates in a changing world. Taiwan J

Obstet Gynecol. 2021;60(1):20–3.

- Harrison MS, Garces AL, Goudar SS, Saleem S,

Moore JL, Esamai F, et al. Cesarean

birth in the Global Network for Women’s and

Children’s Health Research: trends in

utilization, risk factors, and subgroups with

high cesarean birth rates. Reprod Health.

2020 Dec 17;17(Suppl 3):165.

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J.

Trends and projections of caesarean section

rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ

Glob Health. 2021;6(6):e005671.

- Osayande I, Ogunyemi O, Gwacham-Anisiobi U,

Olaniran A, Yaya S, Banke-Thomas A. Prevalence,

indications, and complications of caesarean

section in health facilities across Nigeria: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod

Health. 2023;20(1):81.

- Ochieng Arunda M, Agardh A, Asamoah BO.

Cesarean delivery and associated socioeconomic

factors and neonatal survival outcome in Kenya

and Tanzania: analysis of national survey data.

Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1748403.

- Malonga FK, Mukuku O, Ngalula MT, Luhete PK,

Kakoma JB. External anthropometric measurement

and pelvimetry among nulliparous women in

Lubumbashi: risk factors and predictive score of

mechanical dystocia. Pan Afr Med J.

2018;31:69.

- Ymele FF, Nenwa IFW, Fouedjio JH, Fouelifa LD,

Enow RM. Pronostic Maternel et Périnatal de

l’Accouchement chez les Primipares Adolescentes

et Adultes à Yaoundé. Health Sci Dis.

2020;21(3). Available from:

http://www.hsd-fmsb.org/index.php/hsd/article/view/1870

- Nahaee J, Abbas-Alizadeh F, Mirghafourvand M,

Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S. Pre- and during-

labour predictors of dystocia in active phase of

labour: a case-control study. BMC

Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):425.

- Claire BKM, Fortunat MM, John KM, Cibangu K,

Tshimanga K, Michel KN, et al.

Determinants of the Quality of the Cesarean

Section in Mbuji-Mayi City (Democratic Republic

of Congo). Open Access Library Journal. 2021;8(2).

Available from:

http://www.oalib.com/paper/5432975

- Dean AG, Arner TG, Sangam CG, Sunki GC,

Friedman R, Lantinga M, et al. (2011)

Epi InfoTM, a database and statistics program

for public health professionals, Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention,

Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

- The Jamovi project. Jamovi. (Version 2.3)

[Computer Software]. Retrieved from

https://www.jamovi.org. 2022.

- Dumont A. Réduire la mortalité maternelle dans

les pays en développement: quelles sont les

interventions efficaces? Revue de Médecine

Périnatale. 2017;9(1):7–14.

- Kalombo PM. Problématique des accouchements

dystociques au centre de santé maternel et

infantile(CSMI) de Lubao, en République

Démocratique du Congo [Problem of dystocic

childbirth at the maternal and infantile health

center (CSMI) of Lubao, Democratic Republic Of

the Congo]. Tanganyika Journal of

Sciences. 2022;2(1):17–24.

- Dal’Maso E, Rodrigues PRM, Ferreira MG,

Moreira NF, Muraro AP. Cesarean birth and risk

of obesity from birth to adolescence: A cohort

study. Birth. 2022;49(4):774–82.

- Harrison MS, Pasha O, Saleem S, Ali S, Chomba

E, Carlo WA, et al. A prospective

study of maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes

in the setting of cesarean section in low- and

middle-income countries. Obstetricia et

Gynecologica Scandinavica.

2017;96:410–420

- Coelho SJDC, Simões VMF, Batista RFL, Ribeiro

CCC, Lamy ZC, Lamy-Filho F, et al.

Birth by cesarean section and mood disorders

among adolescents of a birth cohort study in

northern Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res.

2021;54(1):e10285.

- John KM, Claire BKM, Cibangu K, Ntumba M,

Fleur MC, Tshimanga K, et al.

Predictive Factors of Childbirth by High in the

City of Mbujimayi (Democratic Republic of

Congo). Open Access Library Journal.

2019;6(12). Available from:

http://www.oalib.com/paper/5424214

- Adelaiye SM, Olusanya A, Onwuhafua PI.

Cesarean section in Ahmadu Bello University

Teaching Hospital Zaria, Nigeria: A five-year

appraisal. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol.

2017;34:34-8

- Allagoa DO, Oriji PC, Tekenah ES, Obagah L,

Ohaeri OS, Mbah KM, et al.

Caesarean Section in a Tertiary Hospital in

South-South, Nigeria: A 3-year Review. European

Journal of Medical and Health Sciences.

2021;3(2):122–7.

- Jombo S, Ossai C, Onwusulu D, Ilikannu S,

Fagbemi A. Feto-maternal outcomes of caesarean

delivery in Federal Medical Centre, Asaba: a two

year review. Afr Health Sci.

2022;22(1):172–9.

- Chill HH, Lipschuetz M, Atias E, Shimonovitz

T, Shveiky D, Karavani G. Obstetric anal

sphincter injury in adolescent mothers. BMC

Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):564.

- Mboua BV, Essiben F, Nana LP et al. Devenir

Maternel et Néonatal après Césarienne dans Trois

Hôpitaux de la Ville de Maroua. Health Sci

Dis. 2022 ;23(3). Available from:

http://www.hsd-fmsb.org/index.php/hsd/article/view/3468

- Vasconcelos A, Bandeira N, Sousa S, Machado

MC, Pereira F. Adolescent pregnancy in Sao Tome

and Principe: are there different obstetric and

perinatal outcomes? BMC Pregnancy and

Childbirth. 2022;22(1):453.

|