|

Introduction

Placenta

praevia (PP) is an obstetric complication

characterised by the presence of the placenta that

is covering the internal cervical os in the third

trimester. The cause of PP is unknown but there

are many known risk factors such as previous PP,

previous uterine surgery, multiparity etc. AS

Anzaku et al. (1) found prior history of CD as the

most common risk factor (40.7%). A recent WHO

publication reported that between 1990 and 2014

the global average CD rate increased from 12.4 to

18.6% with rates ranging, depending on region, (2)

and South African Saving Mothers reported a CD

rate of 28% in 2019, 2020 and 2021. There is a

well-known exponential increase in the risk of PP

with number of prior CD. (3)

The morbidity and

mortality of PP is increased when PP is associated

with PAS. Prior uterine surgery causes PAS with

prior CD as the most common predisposing factor,

(4-5) the decidua basalis abnormally

thin due to failed reconstruction following

disruption so the placenta can attach and invade

the myometrium. IM Usta et al. (6) found that

caesarean hysterectomy was performed only in women

with PAS who had a longer hospital stay, a higher

estimated blood loss, and need for blood

transfusion.

Queen Nandi Regional

Hospital (QNRH) in northern KwaZulu Natal has a

high prevalence of PP probably because of the wide

referral base. No studies on PP have been done

here. Hopefully this study will highlight the

clinical profile, complications and the

shortcomings in the management of PP.

Methods

The study was a

retrospective observational cross-sectional study

to review women’s medical records. The study was

conducted at QNRH which is a rural and regional

referral health facility for 16 district

hospitals. The study population comprised women

diagnosed during antenatal care with PP and

managed at the hospital from 1st

January 2018 to 31st December 2020. A

hospital register was used to identify women

diagnosed with PP. The hospital numbers were used

to retrieve women’s medical records. Through a

pre-designed structure data sheet, demographic

details and clinical information were obtained

including risk factors, medical and obstetric

history, ultrasound findings, gestational age at

diagnosis and delivery, management and

complications (antepartum, intrapartum and

post-partum). Only women with PP found on

ultrasound with a gestational age of ≥ 26 weeks

were included in the study.

Statistical analyses

were performed by using descriptive statistics.

Frequencies and percentages were used for

categorical data. Chi-Square-Test,

Mann–Whitney-Test, Fisher’s exact were used to

determine categorical factors associated with

outcome, applying a significance level α <

0.05, P values, odds ratios and 95 confidence

intervals were given.

The research was

approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics

Committee of the University of KwaZulu Natal

(BREC/00003226/2021), the KwaZulu Natal department

of Health (KZ _202111_002) and the ethic committee

of Queen Nandi Regional Hospital.

Results

Our study population

were women diagnosed with PP during the study

period, a sample size of 114 was required which

was calculated using Stata V15. Single women were

99 (86.8%), married women were 15 (13.2%),

employed were 25 (21.9%), unemployed were 76

(66.7%), students were 10 (8.8%), unknown

occupation were 3 (2.6%). Women with PP who

presented with complaint of per vagina bleeding

were 67 (58.8%). Women who booked before 14 weeks

gestational age were 46 (40.4%), 14- 22 weeks were

38 (33.3%), more than 22 weeks were 27 (23.7%) and

only 3 (2.6%) were unbooked. HIV negative were 63

(55.3%) and HIV positive were 51 (44.7%). Normal

BMI were 28 (24.6%), overweight were 28 (24.6%),

high BMI were 42 (36.8%) and 16 (14.0%) were

unknown. After diagnosis of PP was made, 87(76.3%)

were managed inside the hospital (asymptomatic or

symptomatic) and 27 (23.7%) were managed as

outpatient (asymptomatic). Emergency CD were 64

(56.1%). Regarding haemostasis management, 20

(17.2%) had uterine artery ligation, 1 (0.9%) had

internal iliac artery ligation, 17 (14.7%) had

compressive sutures, 9 (7.8%) had uterine

tamponade, 2 (1.7%) had stepwise

devascularisation, 4 (3.4%) had abdominal swabs

packed post TAH. All women with PAS (n=14) had a

prior CD and all had a total abdominal

hysterectomy, other cause of TAH was post-partum

haemorrhage (PPH) (n=3). No cell saver machine was

used for blood transfusion. General anaesthesia

was administered in 82 (71.9%) women with PP.

|

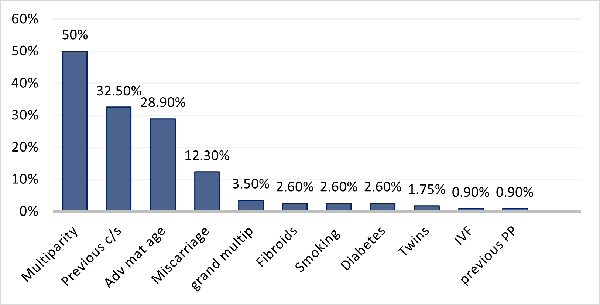

| Fig.

1: Risk factors of women with PP |

|

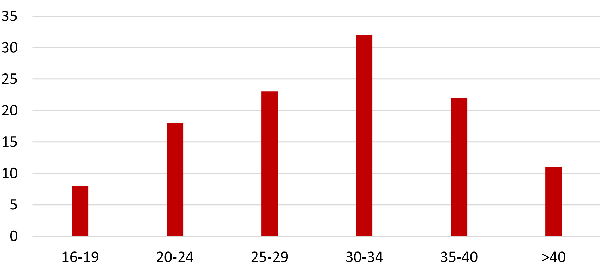

| Fig.

2: Maternal age distributions for women

with PP |

|

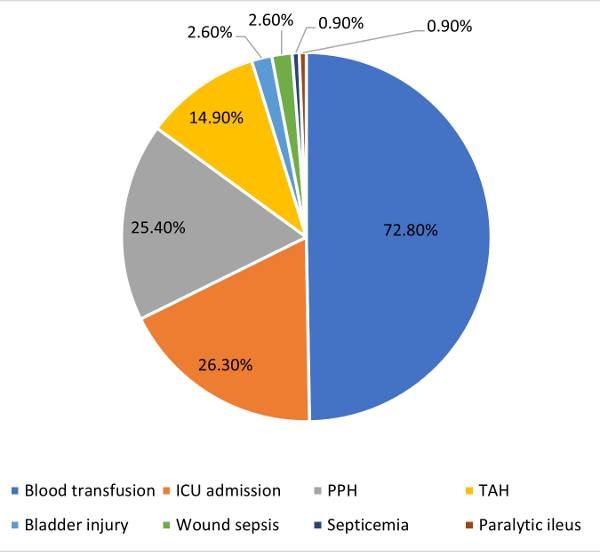

| Fig.

3: Complications of women with PP |

Discussion

This study showed

that most of participants (73.7%) first presented

at health facility before 22 weeks, high number

could be due to health initiative which aims to

support maternal health through the use of cell

phone based technologies integrated into maternal

and child health services. Most women in South

Africa (56%) do not attend health facility before

20 weeks due to numerous barriers such as

transportation, under-resourced clinics with

excessive waiting lines. (7)

The participants in

the study presented with different risk factors,

the most common including: multipara, prior CD and

increasing in maternal age (Fig. 1). The

Increasing in parity, documented to be 50% (table

1) as compared to 57% in study by M. Kollman et

al. (4) may be due to many unsettled

relationships, with single women found to be

86.8%, poor contraception uptake could also be the

reason.

|

Table 1: Obstetric history

|

|

Parity

|

N=114

|

%

|

|

P0

|

15

|

13.2

|

|

P1

|

38

|

33.3

|

|

P2-4

|

57

|

50.0

|

|

≥5

|

4

|

3.5

|

|

Previous mode of delivery

|

N=114

|

%

|

|

NVD

|

77

|

67.5

|

|

Previous CD x1

|

18

|

15.8

|

|

Previous CD x2

|

12

|

10.5

|

|

Previous CD x3 or more

|

7

|

6.1

|

The high prevalence

of prior CD (32.5%) could be the result of

increased CD rate worldwide, (2) and a wide

referral base at QNRH, AS Anzaku et al. (1) and E.

Jaiswal et al. (8) found respectively a prior CD

rate of 40.7% and 35.4%. Surgical disruption of

the uterine cavity is known to cause lasting

damage to the myometrium and endometrium and the

risk of PP is increased with the increased number

of prior CD. (3)

Advanced maternal

age was 28.9% (Fig. 1 and 2), same number (29.3%)

was found by M. Kollman et al. (4) According

to the study conducted by Choi et al. (9) prevalence

of PP increases as the maternal age advances. This

is thought to be due to atherosclerotic changes in

the uterus resulting in under perfusion and

infraction of the placenta, thereby increasing the

size of the placenta.

A low lying placenta

may be found as soon as 18-20 weeks gestational

age when an ultrasound is done for an anomaly

ultrasound but the diagnosis of PP will needs to

be confirmed at around 32 weeks as 90% of PP will

resolve before delivery at term. (10) Early

access to ultrasound seemed to be limited or

delayed in the participants as only 37.7% had

their first ultrasound before 28 weeks gestational

age (Table 2). For women who didn’t have an

ultrasound done early in pregnancy, the diagnosis

may be suspected and confirmed when they present

with per vagina bleeding, this study found 58.8%

of participants presented with per vagina

bleeding.

|

Table 2: Gestational age at

diagnosis and delivery

|

|

Gestational age at diagnosis

(weeks)

|

N

|

%

|

|

<28

|

43

|

37.7

|

|

28-33

|

44

|

38.6

|

|

34-36

|

15

|

13.2

|

|

≥37

|

12

|

10.5

|

|

Total

|

114

|

100

|

|

Gestational age at Delivery

(weeks)

|

N

|

%

|

|

28-33

|

30

|

26.3

|

|

34-36

|

33

|

28.9

|

|

≥37

|

51

|

44.7

|

|

Total

|

114

|

100

|

Per vagina bleeding

is the main reason for early delivery with 56.1%

of participants who required emergency CD. E.

Jaiswal et al. (8) found 81.5% with per vagina

bleeding, with 70.8% who had emergency CD. The

bleeding can be very massive, putting the life of

the woman and her pregnancy in danger, emphasizing

the importance of early access to ultrasound and

early diagnosis.

The detection rate

of PAS was low as only 5 out 14 (35.7%) (Table 3)

were diagnosed by ultrasound with the remainder

diagnosis made intra operatively after failed

separation of the placenta. G Pagani et al. (11)

found a sensitivity of 88% on sonographic

identification of PAS. The combination of

grey-scale and colour Doppler imaging ultrasound

markers is reported to have increased the

sensitivity of ultrasound imaging to around 90%

with negative predictive values ranging between

95% and 98%. (12)

|

Table 3: Ultrasound findings at

diagnosis

|

|

Placenta praevia classification

|

N=114

|

%

|

|

Minor

|

43

|

37.7

|

|

Major

|

71

|

62.3

|

|

Placenta praevia location

|

N=114

|

%

|

|

Anterior

|

49

|

42.9

|

|

Posterior

|

53

|

46.4

|

|

Antero-posterior

|

7

|

6.1

|

|

Lateral

|

5

|

4.4

|

|

Signs of morbid adherence

|

N=14

|

%

|

|

Yes

|

5

|

35.7

|

|

No

|

9

|

64.3

|

Most of participants

were managed as inpatients (76.3%), many of them

came from far with limited access to

transportation or were at high risk of bleeding

and needed to be managed inside the hospital.

Comparison of outcome between inpatient and

outpatient management was not done, due to

insufficient medical notes but Wing et al. (13)

found no difference in outcomes between inpatient

and outpatient management in his randomized

control trial.

Intra operatively,

the main concern is excessive bleeding. The most

common fertility sparing technique used to achieve

haemostasis in the study was uterine artery

ligation (17.2%) while in study by E. Jaiswal et

al. (8) placenta bed compressive sutures were

mostly used (39.2%). A combination of techniques

can be used to achieve haemostasis if one isn’t

successful and because bleeding comes from the

placenta bed, compressive sutures and uterine

tamponade may be among the first to be done.

Most of participants

received general anaesthesia (71.9%), probably due

to the perception that it is safer especially for

major degree PP or PP associated with PAS. JY Hong

et al. (14) compared general and regional

anaesthesia (RA) found the latter was more

superior in elective caesarean section for major

degree PP with regard to maternal haemodynamic and

blood loss but there was no difference in the

incidence of intraoperative or anaesthesia

complications between the 2 types of anaesthesia.

The study found

different complications associated with PP. (Fig.

3) The study found 25.4% of participants had PPH

(table 4), same number (24.6%) found by E. Jaiswal

et al. (8) Lower segment of the uterus

contracts poorly leading to excessive bleeding in

women with major degree PP. In this study, the

risk of PPH increased with the number of prior CD

(5 fold Odds increase with Prior CDx3) (Table 5),

J. Hasegawa et al. (15) had the same observation.

This may be due to prior CD that is associated

with PAS due to an absence or deficiency of

spongiosus layer of the decidua and the main risk

associated with any form of PAS disorder is

massive obstetric haemorrhage, (16) with result

found to be statistically significant in this

study. (Table 5)

|

Table 4: Number of blood units

transfused and estimated blood loss

|

|

Unit of blood transfusion

|

N

|

%

|

|

0

|

31

|

27.2

|

|

1-2

|

48

|

42.1

|

|

3-4

|

18

|

15.8

|

|

5-6

|

12

|

10.5

|

|

7-8

|

5

|

4.4

|

|

Total

|

114

|

100

|

|

Intraoperative estimated blood

loss

|

N

|

%

|

|

<500 ml

|

28

|

24.6

|

|

500-900ml

|

47

|

41.2

|

|

≥1000 ml

|

29

|

25.4

|

|

Unknown

|

10

|

8.7

|

|

Total

|

114

|

100

|

|

Table 5: Postpartum haemorrhage

compared with maternal characteristics

|

|

Postpartum haemorrhage

|

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable

|

n

|

n

|

t

|

p

|

OR

|

95 CI

|

|

Grading of PP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Minor

|

4

|

39

|

43

|

0.002

|

|

|

|

Major

|

25

|

46

|

71

|

|

5.30

|

1.70-16.54

|

|

Total

|

29

|

85

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

Prior delivery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NVD

|

15

|

62

|

77

|

0.02

|

|

|

|

CDx1

|

6

|

12

|

18

|

|

2.07

|

0.67-6.40

|

|

CDx2

|

4

|

8

|

12

|

|

2.07

|

0.55-7.78

|

|

CDx3

|

4

|

3

|

7

|

|

5.51

|

1.11-27.29

|

|

Total

|

29

|

85

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

PAS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

10

|

4

|

14

|

<0.001

|

|

|

|

No

|

19

|

81

|

100

|

|

0.09

|

0.03-0.33

|

|

Total

|

29

|

85

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

Parity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P0

|

5

|

10

|

15

|

0.78

|

|

|

|

P1

|

8

|

30

|

38

|

|

0.53

|

0.14-2.01

|

|

P2-4

|

12

|

45

|

57

|

|

0.78

|

0.23-2.64

|

|

≥5

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

29

|

85

|

114

|

|

|

|

The study found that

the risk of TAH increased with the number of prior

CD, probably due to the association of prior CD

and PAS. All participants diagnosed with PAS had a

TAH. (Table 6) IM Usta et al. (6) and DA Miller et

al. (17) found also an increased risk of PAS with

number of prior CD. There is a place for a

conservative management (leaving the placenta in

situ for spontaneous resorption) when fertility is

still desired, (18) no participant with PAS in

this study was managed conservatively as all had

completed family and were agreeable for TAH after

counselling.

|

Table 6: Hysterectomy compared

with maternal characteristics

|

|

Hysterectomy

|

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable

|

n

|

n

|

t

|

p

|

OR

|

95 CI

|

|

Grading of PP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Minor

|

1

|

42

|

43

|

0.005

|

|

|

|

Major

|

16

|

55

|

71

|

|

11.25

|

1.43-88.57

|

|

Total

|

17

|

97

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

Prior delivery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NVD

|

1

|

76

|

77

|

<0.001

|

|

|

|

CD x1

|

3

|

15

|

18

|

|

15.20

|

1.48-156.21

|

|

CD x2

|

7

|

5

|

12

|

|

106.40

|

10.86-1042.68

|

|

CD x3

|

6

|

1

|

7

|

|

190.00

|

14.61-2470.99

|

|

Total

|

17

|

97

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

PAS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

14

|

0

|

14

|

<0.001

|

|

|

|

No

|

3

|

97

|

100

|

|

0.002

|

0.000-0.021

|

|

Total

|

17

|

97

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

Parity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P0

|

0

|

14

|

14

|

0.06

|

|

|

|

P1

|

3

|

36

|

39

|

|

0.78

|

0.07-9.27

|

|

P2-4

|

10

|

47

|

57

|

|

4.14

|

0.50-34.50

|

|

≥5

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

17

|

97

|

114

|

|

|

|

Majority of

participants (72.8%) in the study received blood

transfusion. (Fig. 3) The risk of blood

transfusion increased with prior CD (5 fold Odds

increase with prior CDx2) (Table 7), WA Grobman et

al. (19) had the same observation but

A Oya et al. (20) found increased risk of blood

transfusion only in major degree PP and not in

prior CD, difference could be due to small number

of prior CD in his study. Our study showed that no

cell saver machine was used even though it was

available. S Malik et al. (21) found the usage of

cell salvage practice was not very effective due

to non-availability of trained staff and

unfamiliarity of techniques, explanation may be

similar in this study, but S Malik concluded that

if it is used efficiently it has a role in

decreasing the need for homologous blood

transfusion and saving cost.

|

Table 7: Blood transfusion

compared with maternal characteristics

|

|

Blood transfusion

|

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable

|

n

|

n

|

t

|

p

|

OR

|

95 CI

|

|

Classification

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Minor

|

26

|

17

|

43

|

0.03

|

|

|

|

Major

|

57

|

14

|

71

|

|

2.66

|

1.14-6.20

|

|

Total

|

83

|

31

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

Parity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P0

|

10

|

5

|

15

|

0.01

|

|

|

|

P1

|

22

|

16

|

38

|

|

0.69

|

0.20-2.40

|

|

P2-4

|

47

|

10

|

57

|

|

2.35

|

0.66-8.39

|

|

≥5

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

83

|

31

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

Prior delivery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NVD

|

50

|

27

|

77

|

0.005

|

|

|

|

CD x1

|

15

|

3

|

18

|

|

2.70

|

0.72-10.6

|

|

CD x2

|

11

|

1

|

12

|

|

5.90

|

0.73-48.50

|

|

≥ CD x3

|

7

|

0

|

7

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

83

|

31

|

114

|

|

|

|

|

PAS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

14

|

0.0

|

14

|

0.01

|

|

|

|

No

|

69

|

31

|

100

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

83

|

31

|

114

|

|

|

|

Placenta praevia is

associated with a high risk of preterm delivery,

mainly due to antepartum haemorrhage. (22) This

study found 26.3% of participants delivered before

34 weeks gestational age (Table 3) as compared to

41.5% by E. Jaiswal et al. (8) Participants who

delivered before 37 weeks were 55.3% as compared

to 45.6% by JM Crane et al. (23) Prematurity

may explain other neonate adverse outcomes found

in the study such as, respiratory problems, low

APGAR and perinatal death (Table 8 and 9).

Respiratory problems were more likely in smaller

babies as compared to bigger babies (Table 10),

steroid for lung maturity was not included in the

study due to insufficient notes, if not given can

explain the respiratory problems in small babies.

|

Table 8: Neonates’ outcome

|

|

Fetal birth condition

|

n

|

%

|

|

Alive good APGAR

|

99

|

85.3

|

|

Alive with low APGAR

|

11

|

9.5

|

|

FSB

|

2

|

1.7

|

|

MSB

|

1

|

0.9

|

|

ENND

|

3

|

2.6

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Birth weight

|

n

|

%

|

|

<1500

|

15

|

12.9

|

|

1500-1999

|

15

|

12.9

|

|

2000-2499

|

18

|

15.5

|

|

2500-3000

|

43

|

37.1

|

|

>3000

|

25

|

21.6

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Baby sex

|

n

|

%

|

|

Male

|

63

|

54.3

|

|

Female

|

53

|

45.7

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

NICU/Nursery stay

|

n

|

%

|

|

Yes

|

39

|

33.6

|

|

No

|

77

|

66.4

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Table 9: Reason for neonate

admission to nursery

|

|

Respiratory problems (RDS, HMD,

TTN)

|

n

|

%

|

|

Yes

|

23

|

19.8

|

|

No

|

93

|

80.2

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Birth weight ≤1500g

|

n

|

%

|

|

Yes

|

15

|

12.9

|

|

No

|

101

|

87.1

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Other reasons

|

n

|

%

|

|

Yes

|

14

|

12.1

|

|

No

|

102

|

87.9

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Unknown

|

n

|

%

|

|

Yes

|

4

|

3.4

|

|

No

|

112

|

96.6

|

|

Total

|

116

|

100

|

|

Table 10: Neonates’ respiratory

problems compared with foetal birth

weight

|

|

Respiratory problems (TTN, RDS,

HMD)

|

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable

|

n

|

n

|

t

|

p

|

OR

|

95 CI

|

|

Birth weight

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<1500

|

6

|

9

|

15

|

<0.001

|

1.71

|

0.40-7.29

|

|

1500-1999

|

8

|

7

|

15

|

|

0.58

|

0.13-2.48

|

|

2000-2499

|

5

|

13

|

18

|

|

0.07

|

0.01-0.42

|

|

2500-3000

|

2

|

41

|

43

|

|

0.13

|

0.02-0.77

|

|

>3000

|

2

|

23

|

25

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

23

|

93

|

116

|

|

|

|

This study being the

first done at QNRH, add to the body of evidence

the morbidity associated with PP. Future

researchers may use this study as a reference for

further studies. Clinicians may also refer to this

study to better understand the condition.

Limitations and strengths

This was a

retrospective study with recordkeeping not optimal

in some cases. There were no maternal deaths. This

study is the first in this rural health

institution, identified maternal risk factors

associated with bad outcome and findings could be

used to improve management of women with PP.

Conclusion

Prior history of CD

is a common risk factor for PP, when associated

with PAS, there is an increased risk of

complications such as TAH, PPH and blood

transfusion. Prematurity is a major concern in

women with PP. Limiting the number of caesarean

section in future will decrease the incidence of

PP and its complications. Further research may

involve outcome of women with PP associated with

PAS and manage conservatively by leaving the

placenta in situ.

Acknowledgements: The

authors thank all those who support this study, Dr

N. Mayat, Dr P. Makinga, Dr Motsema, Sister

Tshangase, and Catherine Conneli.

References

- Anzaku A, Musa J. Placenta praevia: incidence,

risk factors, maternal and foetal outcomes in a

Nigerian teaching hospital. Jos Journal of

Medicine. 2012;6(1): p. 42-46.

https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1049152

- Harrison MS, Goldenberg RL. Caesarean section

in sub-Saharan Africa. Maternal Health,

Neonatology and Perinatology.

2016;2(1):1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-016-0033-x

- Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The

association of placenta praevia with history of

caesarean delivery and abortion: a

meta-analysis. American Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

1997;177(5):1071-1078.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378 (97)70017-6

- Kollmann M, Gaulhofer J, Lang U et al.

Placenta praevia: incidence, risk factors and

outcome. The Journal of Maternal-Foetal and

Neonatal Medicine. 2016;29(9):1395-1398.

https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1049152

- Matsuzaki S, Mandelbaum RS, Sangara RN, et al.

Trends, characteristics, and outcomes of

placenta accreta spectrum: a national study in

the United States. American Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

2021;225(5):534. e1-534. e38.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.233

- Usta IM, Hobeika EM, Musa AA et al. Placenta

praevia-accreta: risk factors and complications.

American Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology. 2005;193(3):1045-1049.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.037

- Haddad DN, Makin JD, Pattinson RC et al.

Barriers to early prenatal care in South Africa.

International Journal of Gynaecology and

Obstetrics. 2016;132(1):64-67.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.041

- Jaiswal E, Aggarwal N, Suri V et al. Clinical

profile and outcome of patients with placenta

praevia: a study at a tertiary care referral

institute in Northern India. International

Journal of Reproduction, Contraception,

Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

2018;7(7):2560.

https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20182861

- Choi SJ, Song SE, Jung KL et al. Antepartum

risk factors associated with peripartum

caesarean hysterectomy in women with placenta

praevia. American Journal of Perinatology.

2007;37-41.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1004834

- Oyelese Y, Smulian JC. Placenta praevia,

placenta accreta, and vasa praevia. Obstetrics

and Gynaecology. 2006;107(4):927-941.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000252288.13209.40

- Pagani G, Cali G, Acharya G, et al. Diagnostic

accuracy of ultrasound in detecting the severity

of abnormally invasive placentation: a

systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta

Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

2018;97(1):25-37.

https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13238

- D'Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal

identification of invasive placentation using

ultrasound: systematic review and meta‐analysis.

Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

2013;42(5):509-517.

https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13194

- Wing DA, Paul RH, Millar LK. Management of the

symptomatic placenta praevia: a randomized,

controlled trial of inpatient versus outpatient

expectant management. American Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

1996;175(4):806-811.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378 (96)80003-2

- Hong JY, Jee YS, Yoon HJ et al. Comparison of

general and epidural anaesthesia in elective

caesarean section for placenta praevia totalis:

maternal hemodynamic, blood loss and neonatal

outcome. International Journal of Obstetric

Anaesthesia. 2003;12(1):12-16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-289x (02)00183-8

- Hasegawa J, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, et al.

Predisposing factors for massive haemorrhage

during caesarean section in patients with

placenta praevia. Ultrasound in Obstetrics

and Gynaecology. 2009;34(1):80-84.

https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.6426

- Allen L, Jauniaux E, Hobson S et al. FIGO

consensus guidelines on placenta accreta

spectrum disorders: nonconservative surgical

management. International Journal of

Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12409

- Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical

risk factors for placenta praevia–placenta

accreta. American Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology. 1997;177(1):210-214.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378 (97)70463-0

- Sentilhes L, Ambroselli C, Kayem G, et al.

Maternal outcome after conservative treatment of

placenta accreta. Obstetrics and

Gynaecology. 2010;115(3):526-534.

https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e3181f738d8

- Grobman WA, Gersnoviez R, Landon MB, et al.

Pregnancy outcomes for women with placenta

praevia in relation to the number of prior

caesarean deliveries. Obstetrics and

Gynecology. 2007;110(6):1249-1255.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.415

- Oya A, Nakai A, Miyake H et al. Risk factors

for peripartum blood transfusion in women with

placenta praevia: a retrospective analysis. Journal

of Nippon Medical School.

2008;75(3):146-151.

https://doi.org/10.1272/jnms.75.146

- Malik S, Brooks H, Singhal T. Cell saver use

in obstetrics. Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology. 2010;30(8):826-828.

https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2010.511727

- Long SY, Yang Q, Chi R et al. Maternal and

neonatal outcomes resulting from antepartum

haemorrhage in women with placenta praevia and

its associated risk factors: A single-centre

retrospective study. Therapeutics and

Clinical Risk Management. 2021;31-38.

https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.s288461

- Crane JM, Van den Hof MC, Dodds L et al.

Neonatal outcomes with placenta praevia. Obstetrics

and Gynecology. 1999;93(4):541-544.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844 (98)00480-3

|