|

Introduction

Filariasis

are tissue helminthiases caused by white filiform

worms or nematodes transmitted by arthropods

(diptera: mosquitoes, flies and midges) (1). Nine

filarial species have been described in humans.

Depending on their impact, they are divided into

pathogenic filariases (onchocerciasis, loasis,

brugiosis, wucheriosis or brancoftosis) and low-

or non-pathogenic filarioses (M. perstans, M.

rodhaini, M. ozzardi and M.

streptocerca mansonellosis) (2). In Gabon,

5 species are encountered: L. loa, M.

perstans, O. volvulus, M. streptocerca and M.

rodhaini (3). Because of their chronicity,

these filariases can become systemic diseases,

affecting organs such as the heart, lungs, kidneys

and liver, and leading to a dysregulation of the

host's immune response (4). With almost a billion

people exposed to these parasites and over 200

million affected, they are widespread throughout

the world. Because of the disability they cause

among African workers, the people living in

high-risk areas have been estimated at nearly 14.4

million cfa francs (5). Loa loa

filariasis is a parasitosis endemic to the

tropical forests of Central and West Africa. It is

transmitted by a hematophagous female fly of the

genus Chrysops (6). More than 15-20

million people are infected with L. loa (7). In

endemic countries such as Cameroon, Central

African Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of

Congo, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, Loa loa

filariasis is a real public health problem. After

malaria, it is the second most common cause of

parasitological consultations. It is also found in

endemic areas in southern Nigeria, Chad, Sudan and

on its border with Kenya, as well as in Angola

(8).

Loa loa

filariasis has received little attention and is

not included in the list of neglected tropical

diseases such as lymphatic filariasis and

onchocerciasis (6). It attracts attention mainly

because of the embarrassing symptoms it manifests,

such as pruritus, migration of adult worms into

the eye and so-called Calabar edema (9). It

contraindicates the treatment of "river

blindness", also known as onchocerciasis, in cases

of coinfection due to severe, even fatal,

neurological reactions (10). However, in 2016, it

was shown that this pathology is more dangerous

than it appears. In fact, in infected people over

the age of 24 with a parasitaemia greater than or

equal to 30,000 mf/ml of blood, it would increase

the risk of mortality (7). Also, in cases of

hyperparasitemia of Loa loa filariasis,

serious adverse effects can occur during treatment

with diethylcarbamazine (DEC) and ivermectin,

requiring close monitoring of treatment that

prevents the mass administration of antifilarial

drugs, aimed at controlling other filaria in areas

where Loa loa is coendemic (11).

Numerous epidemiological studies on Loa

loa filariasis, have been conducted

throughout the West and Central African forest

block. They have indicated Cameroon as the most

important focus of the disease, with a prevalence

of over 50% in four localities (12). In Gabon, a

country covered by an immense tropical forest,

despite the existence of a study that revealed a

prevalence of Loa loa filariasis of

22.4% in 4392 individuals aged at least 15

throughout the country (3) and a more recent one,

which reported a prevalence of 9.27% (95% CI:

[0.05. 0.15]) among pregnant women at the

Sino-Gabonese Friendship Hospital in Franceville

(13), the benign nature attributed to Loa loa

filariasis contributes to making this disease a

public health problem in the country. It is in

this context that this study was undertaken, with

the overall aim of determining the prevalence and

risk factors associated with Loa loa

filariasis in South-eastern Gabon.

Materials and Methods

Presentation of the study and sampling

site:

Sampling for the

present study was carried out at the Paul MOUKAMBI

Regional Hospital in Koula-Moutou (PMRHKM) in the

Mikoumou district of Koula-Moutou (Central-eastern

Gabon). This healthcare institution is located in

the MIKOUMOU district, at a latitude of .1.12724°

or 1°7'38'' South and a longitude of 12.47764° or

12°28'40'' in the North-east of the town of

Koula-Moutou, capital of the Ogooué-Lolo province.

It is located at the entrance to the town from

Lastourville, 800 m from the crossroads on the

paved road. Inaugurated in 2002 by President OMAR

BONGO, the PMRHKM comprises 15 buildings housing

several departments, including the laboratory.

Koula-Moutou is a semi-urban town characterized by

alternating dwellings and equatorial vegetation.

Human activities are based on administrative work,

hunting, fishing, agriculture, trade and so on.

The Koula-Moutou-Lastourville and

Koula-Moutou-Pana axes are characterized by the

presence of large expanses of equatorial

vegetation all along the road, and human

activities are based on forestry work, hunting,

fishing, agriculture and so on.

|

Fig

1: Study Site Map

|

Type, period

and population of the study

Conducted from April

03 to July 31, 2023, this prospective,

cross-sectional, analytical study involved

randomly selected men and women aged at least 15

years, who had come during the study period to be

diagnosed for Loa loa filariasis at the

biomedical analysis laboratory of the PMRH in

Koula-Moutou, and who met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion

and exclusion criteria for study participants:

Only people who

- Were at least 15 years old

- Had consented to participate in the study

- Had agreed to complete the survey

questionnaire

were included.

People who did not

wish to take part in the study, or whose

examination results were unusable, were excluded.

Determining

sample size

To estimate the

prevalence and risk factors associated with Loa

loa filariasis in the town of Koula-Moutou

and surrounding departments, the study sample size

was determined using the single-proportion

population formula as used elsewhere, positing the

formula:

n = (Zα / 2)2

X (P, (1 - P)2 / (d)2) (14)

In this, n

represents the number of the sample size, Z α /2

is the standard normal deviation (1.96)

corresponding to a 95% confidence interval (CI), P

is the prevalence of Loa loa filariasis.

In the absence of P values obtained elsewhere, or

in previous studies in the town of Koula-Moutou

and surrounding departments, this P value was

taken to be 50%. d is taken to be the

precision/marginal error (d = 0.05) or 5%.

Initially, the sample size determined for the

study was 273. As it has been applied in two

studies elsewhere, errors resulting from the

probability of non-compliance or abandonment were

minimized, the sample size was increased by 10%

(15,16). Finally, the sample size used in the

present study was 300 participants.

Sample

collection

After signing the

informed consent, venous blood samples (at the

elbow crease) were taken in EDTA tubes between 11

am and 3 pm (due to daytime activity) at the

laboratories of the PMRH in Koula-Moutou.

EDTA

tube:

This is a

purple-capped tube containing an anticoagulant:

Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetic (EDTA) and a calcium

chelator (which lowers calcium). Plasma is

obtained from the EDTA tube. This is the tube par

excellence for CBC, CV, GE, RMF and PCR.

Parasitological

diagnosis of Loa loa filariasis

Loa loa

filariasis is diagnosed using two techniques:

fresh blood and leucoconcentration. Detection of

the parasite as an adult or in the microfilarial

stage provides a definitive confirmation of

infection. Adult filariae are rarely found; they

can be found and extracted as they pass under the

conjunctiva or skin. A blood sample is used to

test for microfilariae.

Direct

examination of fresh blood: 10 µL

of whole blood is placed between a slide and a

coverslip and observed with a light microscope at

x10 and x40. Microscopic observation of fresh

blood enables the presence of microfilariae to be

detected thanks to their rapid movements. Indeed,

Loa loa is a long worm with low mobility

(diurnal) at the PMRH laboratories in

Koula-Moutou.

Concentration

techniques: Also known as the

leucoconcentration technique, this is performed if

the direct examination is negative and is carried

out as follows:

Decantation

Whole blood (EDTA)

is centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes, then the

supernatant (plasma) is removed.

Hemolysis

1

Add 2 mL saline (9%

NaCl) and 1 mL saponin (2%), then invert the tube

successively and leave for 10 minutes. Then

centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes and discard

the supernatant.

Hemolysis

2

Add 2 mL saline (9%

NaCl) and 1 mL saponin (2%), then successively

invert the tube and centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 5

minutes, discarding the supernatant.

Washing

Add 3mL of saline

(9% NaCl) to the pellet, successively invert the

tube and centrifuge at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes,

then discard the supernatant and drain.

Reading

Place the pellet

between slide and coverslip and read under the

microscope at x10 and x40.

Other

parasitological diagnostics are also performed,

such as:

- Thin smear and thick drop tests: These are

used to identify microfilariae on the basis of

characteristics specific to each species (size,

coloring or absence of the sheath, appearance

and size of nuclei, etc.).

- Blood microfilaria count: useful before

starting treatment with a microfilaricide.

Survey

questionnaire

Patients were

interviewed to collect data on potential risk

factors for Loa loa filariasis using a

structured questionnaire, covering

socio-demographic information, such as age,

marital status, instruction level, professional

status, residence (Urban or rural)), residence

duration, and housing conditions. In addition,

behavioral risk factors and medical history of

study participants, such as tattooing, blood

transfusion, surgery, clinical signs, were

addressed

Quality

assurance

Using standardized

data collection tools, data quality was ensured by

pre-testing questionnaires on 5% of participants,

after appropriate training of staff in data

collection and management of an integrated quality

control system at the Paul MOUKAMBI Regional

Hospital in Koula-Moutou (PMRHKM). All laboratory

procedures were carried out in accordance with

standard operating procedures.

Ethical

considerations:

Ethical

authorization was obtained from the Director

General of the Centre Hospitalier Régional Paul

MOUKAMBI de Koula-Moutou, which maintains

partnerships with the USTM Faculty of Sciences. An

internship agreement was obtained from the Dean of

the Faculty of Science to conduct the study in the

said structure. Written informed consent was

obtained from each participant, who was informed

in advance of the right to terminate participation

in the present study at any time. Confidentiality

of information was maintained by coding and

storage in a lockable cabinet. Clinicians were

informed of the results for patient management.

Statistical analysis:

Data collected were

entered into a Microsoft Excel 2013 spreadsheet,

cleaned and then analyzed with R software version

3.6.1. Pearson's chi-square, Odds ratios, and 95%

confidence intervals were used to find potential

associations between risk factors and Loa loa

filariasis. P-values were determined and

considered significant when less than or equal to

0.05.

Results

Prevalence

of Loa loa filariasis among study

participants (N =300).

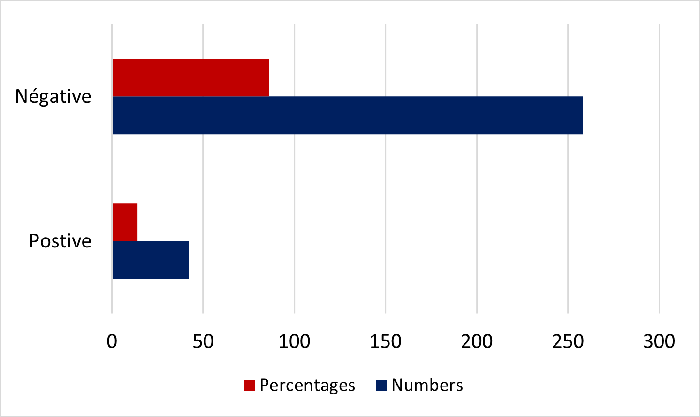

A total of 300

participants were registered for this study. With

a sex ratio (M/F) of 0.60, women were in the

majority. With a mean age of 26.7 ± 17.45 years,

the majority of study participants, 60 (20%), were

aged between 31 and 40 years, and 188 (62.67%)

were women. Diagnosis for Loa loa

filariasis indicated that 42 participants suffered

from this disease, a prevalence of 14% (95% CI:

[0.10. 0.18]), compared with 86%, or 258 negative

results [Figure 2].

|

| Figure

1 : Prevalence of Loa loa

filariasis among study participants (N

=300). |

Prevalence

of Loa loa filariasis according to

socio-demographic characteristics of the study

population, (N=300).

Statistically

significant associations between dependent and

independent variables were found in univariate

analyses of the prevalence of Loa loa

filariasis according to sociodemographic

characteristics. Among Loa loa

filariasis-positive patients in the study, those

aged between 61 and 70 years (OR = 2.66, 95% CI :

[1.09 ; 6.48] p =0.003*) , female (OR = 2.58, 95%

CI : [1.33 ; 5.01] p =0.042* ), retired (e) (OR =

3.35, 95% CI : [1.08; 10.35] p =0.03*), living in

rural areas (OR = 6.39, 95% CI: [3.06; 13.35] p

<0.0001), living in average conditions (OR =

5.15, 95% CI: [2.54; 10.43] p <0.001), were

statistically associated with Loa loa

filariasis Further study using multivariate

logistic regression of the variables indicated

that women (adjusted OR= 56.9, 95% CI: [1.71;

1893.6] p =0.024*) were fifty-seven times more

likely to suffer from Loa loa filariasis

(Table 1).

|

Table 1: Univariate and

multivariate analyses of the prevalence

of Loa loa filariasis,

according to socio-demographic

characteristics of study participants

(N=300).

|

|

Variables

|

Total number of people diagnosed

N (%)

|

Prevalence of Loa loa

filariasis

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|

Positive N (%)

|

Negative N (%)

|

Crude OR CI 95%

|

p

|

Adjusted OR CI 95%

|

p

|

|

Age groups (years)

|

|

≤ 20

|

44 (14.67)

|

6 (13.63)

|

38 (86.37)

|

0.96

[0.38 ; 2.43]

|

0.94

|

-

|

-

|

|

21 - 30

|

56 (18.67)

|

4 (7.14)

|

52(92.86)

|

Reference

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

31 - 40

|

60 (20)

|

5 (8.33)

|

55 (91.67)

|

0.5

[0.19 ; 1.33]

|

0.16

|

-

|

-

|

|

41 - 50

|

47 (15.67)

|

4 (8.51)

|

43 (91.49)

|

0,53

[0.18 ; 1.56]

|

0.24

|

-

|

-

|

|

51 - 60

|

29 (9.67)

|

6 (20.69)

|

23 (79.31)

|

1.17 [0.65 ; 4.46]

|

0.28

|

-

|

-

|

|

61 - 70

|

29 (9.67)

|

8 (27.59)

|

21 (72.41)

|

2.66 [1.09 ; 6.48]

|

0.027*

|

-

|

-

|

|

71 - 80

|

20 (6.67)

|

5 (25)

|

15 (75)

|

2.19 [0.75 ; 6.38]

|

0.14

|

-

|

-

|

|

≥ 81

|

15 (4.98)

|

4 (26.67)

|

11 (73.33)

|

2.64 [0.8 ; 8.76]

|

0.15

|

-

|

-

|

|

Gender

|

|

Male

|

112 (37.33)

|

24 (21.42)

|

88 (78.58)

|

Reference

|

|

1

|

|

|

Female

|

188 (62.67)

|

18(9.57)

|

170 (90.43)

|

2.58 [1.33; 5.01]

|

0.042*

|

56.9 [1.71; 1893.6]

|

0.024*

|

|

Marital status

|

|

Married

|

43 (14.33)

|

9 (20.93)

|

34 (79.07)

|

Reference

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Single

|

117 (29)

|

12 (10.26)

|

105 (89.74)

|

0.58 [0.28; 1.18]

|

0.14

|

0.64 [0,02; 239.9]

|

0.89

|

|

Cohabiting

|

132 (44)

|

20 (15.15)

|

112 (84.85)

|

2 [1.05; 3.81]

|

0.61

|

8,8 [0,12; 128.3]

|

0.51

|

|

Widowed

|

8 (2.67)

|

1 (12.5)

|

7 (87.5)

|

0.87 [0.1; 7.26]

|

0.90

|

-

|

-

|

|

Professional status

|

|

Civil servant

|

41 (13.67)

|

6 (14.63)

|

35 (85.37)

|

Reference

|

|

1

|

-

|

|

Pupil/Student

|

67 (22.33)

|

14 (20.9)

|

53 (79.1)

|

1,93 [0.95; 3.92]

|

0.065

|

-

|

-

|

|

Unemployed

|

86 (28.67)

|

8(9.30)

|

78 (90.7)

|

0.56 [0.25; 1.27]

|

0.16

|

-

|

-

|

|

Farmer

|

91 (30.33)

|

9 (9.89)

|

82 (90.11)

|

0,59 [0.27; 1.29]

|

0.18

|

4.46 [0.075; 259.7]

|

0.471

|

|

Retired

|

15 (5)

|

5 (33.33)

|

10 (66.67)

|

3.35 [1.08; 10.35]

|

0.03*

|

-

|

-

|

|

Instruction level

|

|

Illiterate

|

41 (13.67)

|

2 (4.88)

|

39 (95.12)

|

Reference

|

|

1

|

|

|

Primary

|

70 (23,33)

|

19 (27.14)

|

51 (72.86)

|

3.35 [1.7; 6.62]

|

0.000*

|

0.722 [0.001; 654.5]

|

0.925

|

|

Secondary

|

168 (56)

|

20 (11.90)

|

148 (88.1)

|

0.45 [0.23; 0.87]

|

0.36

|

-

|

-

|

|

University

|

21 (7)

|

1(4.76)

|

20 (95.24)

|

0.56 [0.13; 2.48]

|

0.21

|

-

|

-

|

|

Residence

|

|

Koula-Moutou (semi-rural)

|

190 (63.33)

|

11 (5.79)

|

179 (94.21)

|

Reference

|

‘

|

1

|

-

|

|

Other (rural)

|

110 (36.67)

|

31(28.18)

|

79 (71.82)

|

6.39 [3.06; 13.35]

|

<0.0001

|

-

|

-

|

|

Resident for (years)

|

|

≤ 10

|

82

(27.33)

|

6 (7.32)

|

76 (92.68)

|

2.51 [1.02 ; 6.2]

|

0.63

|

]

|

-

|

|

≥ 10

|

218

(72.67)

|

36

(16.51)

|

40

(83.49)

|

Reference

|

|

1

|

|

|

Housing conditions

|

|

Average

|

117 (39)

|

39 (33.33)

|

78 (66.67)

|

5.15 [2.54; 10.43]

|

<0.001

|

-

|

-

|

|

Good

|

183 (61)

|

3 (35.57)

|

180 (64.43)

|

Reference

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

OR = odds ratio; CI= confidence interval;

* = significant test

|

History and

clinical and paraclinical aspects associated

with the prevalence of Loa loa

filariasis in study participants. (N = 300)

To test the

association between Loa loa filariasis

exposure and the medical history and clinical

signs of the study participants, crude and

multivariate logistic regression analyses of the

variables were carried out. It was found that only

study participants with clinical signs such as

pruritus, dermatitis or Calabar edema (OR = 0.16,

95% CI: [0.08; 0.32] p <0.0001) were at greater

risk of developing Loa loa filariasis

than other participants. Multivariate logistic

regression, on the other hand, indicated no

statistically significant association between

participants' clinical signs or medical history

and Loa loa filariasis Table 2.

|

Table 2: Univariate and

multivariate logistic regression

analysis of the prevalence of Loa

loa filariasis, according to the

medical history and clinical signs of

study participants (N = 300).

|

|

Variables

|

Total number of people diagnosed

N (%)

|

Prevalence of Loa loa

filariasis

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|

Positive N (%)

|

Negative N (%)

|

Crude OR CI

95%

|

p

|

Adjusted OR CI

95%

|

p

|

|

Tattoo

|

|

Yes

|

56 (22.95)

|

7 (12.5)

|

49 (87.5)

|

Reference

|

|

1

|

|

|

No

|

244 (77.95)

|

35 (14.34)

|

209 (85.66)

|

0.85 [0.36; 2.03]

|

0.89

|

-]

|

-

|

|

History of surgery

|

|

Yes

|

44 (14.67)

|

11 (25)

|

33 (75)

|

1.97 [0.92; 4.23]

|

0.122

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

256 (8.33)

|

31 (12.11)

|

225 (87.89)

|

Reference

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

History of blood transfusion

|

|

Yes

|

11 (3.67)

|

4 (36.36)

|

7 (63.64)

|

3.77 [1.05; 13.49]

|

0.08

|

-

|

-

|

|

No

|

289 (96.33)

|

38 (13.15)

|

251 (86.85)

|

Reference

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

|

|

Clinical signs (pruritus,

dermatitis, Calabar edema)

|

|

Yes

|

117 (39)

|

25 (21.37)

|

92 (78.63)

|

0.16 [0.08; 0.32]

|

<0.001

|

1.9 [0.13; 26.32]

|

0.65

|

|

No

|

183 (61)

|

17 (9.29)

|

166 (90.71)

|

Reference

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

|

OR = odds ratio; CI= confidence interval;

* = significant test

|

Discussion

Highly endemic in

Central African countries such as Gabon, and the

cause of a high disease burden in these countries,

Loa loa filariasis is a serious human

parasitosis. In order to design, plan and evaluate

appropriate intervention strategies against this

disease, knowledge of its epidemiology,

transmission, distribution and extent, as well as

the associated risk factors, is required (17).

With the main objective of determining the

prevalence and risk factors associated with Loa

loa filariasis: case of Koula-Moutou and

surrounding departments, South-central Gabon, The

present study reported a prevalence of Loa

loa filariasis of 14% (95% CI: [0.10-

0.18]), This result is similar to that found in a

previous study (18). However, it is higher than

that obtained by a study elsewhere, which found an

average prevalence of L. loa in the

village of 6.3% (19), and lower than that of

another study, conducted in Cameroon, which found

an overall prevalence of loasis of 27.3% (20) and

that of another study conducted in another region

of Gabon, a prevalence of Loa loa

microfilaremia of 22.4% was reported in one study

(3). The variability of these results could be

explained, on the one hand, by the number of

participants recorded in each study and the

diagnostic methods used. On the other hand,

knowing that there is a periodicity of Loa

loa microfilaremia (21), the difference in

periods, regions and years of the studies may

influence these results.

Contrary to studies

that reported that the 18-28 age group was

statistically more associated with filariasis than

other age groups (22), or that the maximum load of

Loa loa microfilariae, was found in

individuals aged 35-49 years (20), univariate

analyses of the prevalence of Loa loa

filariasis according to sociodemographic

characteristics, history, medical, and clinical

signs of study participants, indicated that being

aged between 61 and 70 years, was significantly

associated with Loa loa filariasis. This

finding is in line with a study that indicated

that the prevalence of Loa loa

microfilaremia was highest (14.3%) in people aged

between 65 and 84 years (18). This may reflect

this age group's greater exposure to chrysop

bites than younger groups. Most elderly people are

also exposed to a number of factors which may

contribute to their predisposition to infections,

such as impaired immune function (23).

Contrary to the

results obtained in previous studies, which

reported that men were likely to have a higher

prevalence of Loa loa filiarisis than

women (24), a statement also supported by

epidemiological data from central Cameroon, where

the prevalence of Loa loa filariasis was

significantly higher in men than in women (25), in

the present study, he reported that factors such

as female gender, widow, retired, living in rural

areas, housed in average conditions, were

significantly associated with Loa loa

filariasis. This result, confirmed by multivariate

logistic regression analysis, is in line with a

study carried out elsewhere, in which a female was

more likely to report a history of eyeworm than a

male subject (26). This can be justified by the

fact that, in the African context, even a widow,

the woman is the pillar of the family, and the

domestic chores performed by the latter constitute

so many challenges to their health that weigh on

their perception of it. They may also deteriorate

their functional health, due to the physical

efforts required (27). The women in the present

study, residing in rural areas and housed in

average conditions, were significantly associated

with Loa loa filariasis. Now retired,

their main activities were farming and fishing,

which are carried out in forests. This result,

although contrary to that of a study on the

subconjunctival and intraocular presence of adult

Loa loa in populations living in urban

centers (28), is however, in line with a study

that indicated that Loa loa and other

filariases are established diseases observed in

villages and rural communities in endemic areas

(12). In addition, most homes are surrounded by

vegetation or forest, potential reserve for Chrysops,

the loase vector (22). In the present study, it

was reported that only study participants with

clinical signs such as pruritus, dermatitis or

Calabar edema were more likely to develop Loa

loa filariasis than other participants.

This result is in line with that of a study

conducted in Burkina Faso, in which transient

angioedema (Calabar edema) and pruritus were

observed in a patient diagnosed with Loa loa

filariasis (29). Multivariate logistic regression

showed no statistically significant association

between clinical signs or medical history of

participants and Loa loa filariasis.

Study limitations

Despite the contributions made, the present study

has certain limitations that should be highlighted

for future studies. Within the conceptual

framework of this study, a number of factors were

identified upstream of the living context of the

Koula-Moutou populations and the socio-demographic

characteristics likely to influence Loa loa

filariasis. Firstly, clinical signs based on a

questionnaire are highly subjective. Blood smear

staining and concentration techniques used in this

study are limited. Detection of Loa loa

filariasis in peripheral blood is insensitive, as

only 30% of individuals are microfilaremic, while

70% are amicrofilaremic with a variety of clinical

signs (30). In the presence of an apparently

healthy individual with occult infections, the

negative serological screening test could be

biased. The application of nucleic acid-based

detection techniques, such as polymerase chain

reaction (PCR), reverse transcriptase PCR

(RT-PCR), loop-mediated isothermal amplification

and lateral flow assays (LFA), or the detection of

biomarkers, such as immunoglobulin 4 (IgG4),

antibodies directed against Loa loa

antigens, would have been appropriate to prevent

infection in the participants of the present

study.

Conclusion and Outlook

By providing key

information, the results of the present study show

very active transmission of Loa loa

filariasis in Koula-Moutou and surrounding

departments, as suggested by the prevalence rate.

The latter was clearly associated with

socio-demographic variables of the study

participants, such as being aged between 61 and

70, female, retired, living in rural areas, living

in average conditions and presenting clinical

signs such as pruritus, dermatitis or Calabar

swelling. These results could guide Gabonese

health authorities in the control and prevention

of Loa loa filariasis. To implement

appropriate intervention strategies against Loa

loa filariasis, Gabonese health authorities

should introduce molecular (qPCR) and

immunological diagnostic methods, such as the use

of biomarkers, which could help identify the true

profile of Loa loa infection, beyond

pathognomonic signs such as the presence of

microfilariae or attested ocular passage, specific

but not sensitive enough to detect all clinical

cases; in this case, biomarkers may be useful in

areas where this condition is endemic.

Acknowledgments

We would like to

thank all the participants of this study, the

Regional Health Department of the Centre-East, in

Koula-Moutou. We also thank, the management of the

Paul Moukambi regional hospital in Koula- Moutou,

and the staff of the medical analysis laboratory,

for their availability.

References

- Sarwar M. Typical flies: Natural history,

lifestyle and diversity of Diptera. In Life

Cycle and Development of Diptera.

IntechOpen. 2020

- Jones-Sheets MA, Chen M, Cruz JC. Cutaneous

Filariasis in an American Traveler. Cutis,

2020;106(4): E12-E16.

- Akue JP, Nkoghe D, Padilla C et al.

Epidemiology of Concomitant Infection Due to Loa

loa and Mansonella perstans in

Gabon. PLoS. 2011;5(10):e1329

- Wanji S, Ndongmo C, Fombad WP et al. Impact of

repeated annual community treatment with

ivermectin on parasitological indicators of

loasis in Cameroon: implications for the

elimination of onchocerciasis and lymphatic

filariasis in Loa loa co-endemic areas

in Africa.. PLoS Neglected Tropical

Diseases. 2018;12(9):e0006750.

- Zoure HGM, Wanji S, Noma M et al. The

geographic distribution of Loa loa in

Africa: results of large-scale implementation of

the Rapid Assessment Procedure for Loiasis

(RAPLOA). PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

2011;5(6):e1210.

- Pallara E, Cotugno S, Guido G et al. Loa

loa in the Vitreous Cavity of the Eye: A

Case Report and State of Art. Am J Trop Med

Hyg. 2022;107(3):504–16. Available at:

https://doi.org/doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0274.

- Chesnais CB, Takougang I, Paguele M, Pion SD,

Et Boussinesq M. Excess mortality associated

with loiasis: a retrospective population-based

cohort study. The Lancet Infectious

Diseases. 2016;17(1):108-116.

- Kobayashi T, Hayakawa K, Mawatari M et al.

Loiasis in a Japanese Traveler Returning from

Central Africa. Tropical Medicine and

Health. 2015;43(2):149–53. Available at:

https://doi.org/doi: 10.2149/tmh.2015-05

- Barrett MP, Giordani F. Inside Doctor

Livingstone: a Scottish icon meets a tropical

disease. Parasitology.

2017;144(12):1652–1662. Available at:

https://doi.org/doi : 10.1017/S003118201600202X

- Vinkeles Melchers NVS, Coffeng LE, Boussinesq

M et al. Projected Number of People with

Onchocerciasis-Loiasis Coinfection in Africa,

1995 to 2025. Clin Infect Dis.

2020;23;70(11):2281–2289. Available at:

https://doi.org/doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz647.

- Herrick JA, Legrand F, Gounoue R et al.

Post-treatment Reactions after Single-Dose

Diethylcarbamazine or Ivermectin in Subjects

with Loa loa Infection. Clin Infect

Dis. 2017;15;64(8):1017–1025. Available

at: https://doi.org/doi: 10.1093/cid/cix016.

- Dieki R, Nsi-Emvo E, Akue JP. The Human Filai

Loa loa: Update on Diagnostics and

Immune Response. Res Rep Trop Med. 2022

Aug 1;13:41-54. doi: 10.2147/RRTM.S355104. PMID:

35936385; PMCID: PMC9355020

- Adelaïde N, Sima CO, Mba TN et al.

Prevalence of Loa loa filariasis among

pregnant women seen at the Sino-Gabonese

Friendship Hospital in Franceville in 2022. International

Journal of Current Science (IJCSPUB).

2023;13(2).

- Daniel W. W. Biostatistics a Foundation for

Analysis in the Health Science (9th ed.) New

York: John Willey and Sons Inc, USA; 2009

- Tadesse G. The prevalence of intestinal

helminthic infections and associated risk

factors among schoolchildren in the town of

Babile, eastern Ethiopia. The Ethiopian

Journal of Health Development. 2005;19

(2):140–147. doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v19i2.9983

- Sitotaw B, Mekuriaw H, Damtie D. Prevalence of

intestinal parasitic infections and associated

risk factors in children at Jawi Primary School,

Jawi City, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC

Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(1):341.

doi : 10.1186/s12879-019-3971-x.

- Kelly-Hope L, Paulo R, Thomas B, Brito M,

Unnasch TR, Molyneux D. Loa loa vectors Chrysops

spp.: perspectives on research, distribution,

bionomics, and implications for elimination of

lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Parasit

Vectors. 2017 Apr 5;10(1):172. doi:

10.1186/s13071-017-2103-y. PMID: 28381279;

PMCID: PMC5382514

- Ojurongbe O, Akindele Aa, Adeleke Ma, Oyedeji

Mo, Adedokun Sa, Ojo JF. Co-endemicity of

loiasis and onchocerciasis in rain forest

communities in South western Nigeria. PLoS

Negl Trop Dis. 2015 Mar 26;9(3):e0003633.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003633. PMID:

25812086; PMCID: PMC4374772.

- Emukah E, Rakers LJ, Kahansim B et al. In

Southern Nigeria Loa loa Blood

Microfilaria Density is Very Low Even in Areas

with High Prevalence of Loiasis: Results of a

Survey Using the New Loa Scope Technology. Am

J Trop Med Hyg. 2018 Jul;99(1):116-123.

doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0163. Epub 2018 May 10.

PMID: 29761763; PMCID: PMC6085777.

- Mogoung-Wafo AE, Nana-Djeunga HC, Domche A,

Fossuo-Thotchum F, Bopda J, Mbickmen-Tchana S.

Prevalence and intensity of Loa loa

infection over twenty-three years in three

communities of the Mbalmayo health district

(Central Cameroon). BMC Infect Dis. 2019

Feb 13;19(1):146. doi:

10.1186/s12879-019-3776-y. PMID: 30760228;

PMCID: PMC6373160.

- Campillo JT, Louya F, Bikita P, Missamou F,

Pion SDS, Boussinesq M, Chesnais CB. Factors

associated with the periodicity of Loa loa

microfilaremia in the Republic of the Congo. Parasit

Vectors. 2022 Nov 9;15(1):417. doi:

10.1186/s13071-022-05541-y. PMID: 36352480;

PMCID: PMC9647901.

- Kenguele M.H, Meye B, Ndong M T, Mickala P.

Prevalence of haemoparasites in blood donors

attending the Regional Hospital Centre of

Franceville (South Gabon). J Infect Dis

Epidemiol 2022;8:270.

doi.org/10.23937/2474-3658/1510270

- Emch M, Root ED, Carrel M. Health and medical

geography. Guilford Publications. 2017.

- Anosike JC, Onwuliri Co. Études sur la

filariose dans l'État de Bauchi, Nigéria. II.

Prevalence of human filariasis in the Darazo

local government area. Application

Parasitol. 1994;35:242–250

- Pion SDS, Filipe Jan, Kamgno J, Gardon J,

Basañez MG, Boussinesq M. Microfilarial

distribution of Loa loa in the human

host: population dynamics and epidemiological

implications. Parasitology.

2006;133:101–109

- Adeoye GO, Akinsanya B, Otubanjo AO et al.

Prevalences of loiasis in Ondo state, Nigeria,

as evaluated by the rapid assessment procedure

for loiasis (RAPLOA). Annals of Tropical

Medicine & Parasitology.

2008;102(3):215-227. DOI:

10.1179/136485908X267867

- Scodellaro C. Perceived health among the

elderly: from medical criteria to practical

assessments. Retirement and Society.

2014;67(1):19-41

- Okonkwo ON, Hassan AO, Alarape T et al.

Removal of adult subconjunctival Loa loa

in Nigerian city dwellers. PLoS Neglected

Tropical Diseases. 2018;12(11):e0006920

- Ouedraogo NA, Korsaga-Some N, Traore F et al.

Loa loa filariasis in a tropical savanna

area: report of one case in Ouagadougou. Int

J Dermatol. 2020 Apr;59(4):482-483. doi:

10.1111/ijd.14782. Epub 2020 Jan 23. PMID:

31975376

- Dieki R, Eyang Assengone ER, Nsi Emvo E, Akue

JP. Profile of loiasis infection through

clinical and laboratory diagnostics: the

importance of biomarkers. Trans R Soc Trop

Med Hyg. 2023 May 2;117(5):349-357. doi:

10.1093/trstmh/trac116. PMID: 36520072; PMCID:

PMC10153730

|