|

Introduction

Tardive

Dyskinesia is a drug-induced hyperkinetic movement

disorder that is precipitated due to prolonged

exposure to dopamine receptor-blocking agents,

usually antipsychotics, which persists for minimum

30 days after stopping the drug (1). This

condition can be non-reversible and might last a

whole lifetime. The condition can be stigmatizing

and disabling, with detrimental effects on mental

and physical health and quality of life.

The term "tardive,"

or late, differentiates tardive dyskinesia from

various drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms that

usually appear either acutely or very soon after

exposure to dopamine receptor-blocking agents and

that resolve after the drug is discontinued.

Tardive dyskinesia

(TD) is characterized by choreiform, athetoid, and

rhythmic abnormal involuntary movements.

The estimated annual

incidence of TD with first-generation

antipsychotics is 5% to 6% overall (2,3) and 10%

to 25% in adults(4,5). The risk is similar among

various first-generation antipsychotics when used

as dose equivalents.

The estimated annual

risk of tardive dyskinesia with exposure to

second-generation antipsychotics is approximately

4% in the population(6) and 5% to 7% in older

adults(7).

Tardive dyskinesia

is an important marker for patients at risk of

adverse healthcare outcomes and diminished quality

of life.

With a rise access

to psychiatric services and use of antipsychotics,

the need to study tardive dyskinesia becomes

important. The current global prevalence is

believed to be between 15-50% but the true

prevalence is not well studied, especially in the

Indian context.(8)

This study will help

in knowing the extent of tardive dyskinesia among

persons with chronic mental illness in a

Psychiatry Rehabilitation setting in India and

will also give us insights to the factors involved

to help prevent the same.

Materials and Methods:

The present study

was carried out between January 1st, 2021 and

April 2022 in the following rehabilitation centres

in Dakshina Kannada district, after obtaining the

clearance from Institution’s Ethics Committee

(YEC2/658).

- Swadhara women’s home Jeppu, Mangalore.

- Snehalaya asharam, Manjeshwara.

Study

Design: Descriptive type of

observational study, cross-sectional study

Assessment

Tools:

Abnormal

Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS)

The AIMS(9) is a 12

items clinician-rated scale to assess the severity

of dyskinesia in patients taking antipsychotic

medications. Additional items are present to

assess the overall severity, incapacitation, and

the subject’s level of awareness of the movements,

and distress associated with them.

The AIMS has been

used extensively to assess Tardive Dyskinesia in

clinical trials of antipsychotic medications. Due

to its simple design and low assessment time, the

AIMS can be done regularly and effectively by all

clinicians.

Items are scored on

a 0 (none) to 4 (severe) basis. The scale provides

a total score or item 8 can be used in isolation

as an indication of the overall severity of

symptoms.

Kane Schooler

Criteria

It is a diagnostic

criterion(10) for tardive dyskinesia that has

three components and makes use of the AIMS scale

to do so. The components of this criteria are-

- At least 3 months of cumulative exposure to

neuroleptics (antipsychotics).

- Absence of other conditions that might cause

involuntary movements

- At least moderate dyskinetic movements in one

body area (≥ 3 on AIMS) or mild dyskinetic

movements in two body areas (≥ 2 on AIMS)

Sources of

Data/ Sampling Method: Inhabitants of

Swadhara women’s home Jeppu and Snehalaya asharam

who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were

recruited for this study. Written permission was

sought from the Rehabilitation center incharge and

the treating team. Informed consent was then

obtained from all the participants.

Type of sampling:

Convenience sampling

Sample Size

From the published

article, “Prevalence and risk factors associated

with tardive dyskinesia among Indian patients with

schizophrenia” by Rashmin M. Achalia(11) at 5%

level of significance and anticipated prevalence

was 26.4% (from related article) and estimation

error (absolute precision) of 6%

Sample size

calculation was done using the formula, n= [Z2Xp(1-p)]/d2

where, n= sample size d=absolute precision

p=prevalence. Total sample size was found to be

207.

Inclusion

Criteria:

- Patients of ages 18 or above

- Males/ females

- Patients with chronic mental illness currently

on antipsychotics for a minimum period of 3

months duration

Exclusion

Criteria:

- Patients unfit for a formal examination

- Patients with active symptoms of present

mental illness

- Subnormal intelligence clinically

The authors were not

directly involved in the treatment of all these

patients; as they were managed by their primary

physicians and psychiatrists.

Statistical

Analysis:

The data was entered

into a MS-Excel worksheet and cleaned for any

corrections and errors. Further analysis of data

was done using statistical package IBM SPSS

Statistics 26.0.

The nominal and

ordinal variables were presented using frequency

and percentages. The ratio scale variables were

presented using descriptive statistics such as

Mean and SD. Further analysis was done using

Chi-square test and unpaired t-test. The level of

significance was set at 5%. All p-values less than

0.05 were treated as significant.

Results:

Table 1 describes

the sociodemographic variables.

The average age of

study subjects was 45.39 years (SD=12.6336), and

the median age was 47.0 years and modal age was

55.0. The minimum and maximum age was 18 and 74

respectively.

Out of 207 study

subjects, the 139 (67.10%) had psychosis

unspecified/ schizophrenia and 68 (32.90%) had

bipolar disorder. Out of 207 study subjects, 45

(21.73%) had used anticholinergics.

|

Table 1: Sociodemographic data

|

|

Sociodemographic variables

|

Frequency

|

Percentage

|

|

1. Age (years)

|

|

|

|

18-30

|

38

|

18.35

|

|

31-40

|

33

|

15.94

|

|

41-50

|

56

|

27.05

|

|

51-60

|

62

|

29.95

|

|

>60

|

18

|

8.69

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

2. Duration of illness (Years)

|

|

|

|

0-10

|

56

|

27.05

|

|

10-20

|

65

|

31.40

|

|

20-30

|

56

|

27.05

|

|

30-40

|

22

|

10.62

|

|

40-50

|

8

|

3.86

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

3. Family history

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

16

|

7.72

|

|

No

|

191

|

92.27

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

4. ECT received

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

20

|

9.66

|

|

No

|

187

|

90.33

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

5. Anticholinergic drugs

|

|

|

|

No

|

162

|

78.26

|

|

Yes

|

45

|

21.73

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

6. Place of residence

|

|

|

|

Urban

|

96

|

46.37

|

|

Rural

|

111

|

53.62

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

7. Education

|

|

|

|

Illiterate

|

148

|

71.49

|

|

Primary

|

36

|

17.39

|

|

10th Pass

|

16

|

7.72

|

|

12th Pass

|

6

|

2.89

|

|

Graduate

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

8. Marital status

|

|

|

|

Single

|

34

|

16.42

|

|

Married

|

149

|

71.98

|

|

Divorced

|

5

|

2.41

|

|

Separated

|

8

|

3.86

|

|

Widowed

|

11

|

5.31

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

9. Socio-economic status

|

|

|

|

Above poverty line

|

54

|

26.08

|

|

Below poverty line

|

153

|

73.91

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

Figure 1 indicates that 67% participants

were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 33% were

diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

|

Fig.

1: Diagnosis among participants (N=207)

|

Table 2 indicates distribution of study subjects

according to the medicines used.

|

Table 2: Distribution according to

medicines used

|

|

Medicine

|

Frequency

|

Percentage

|

|

Risperidone

|

116

|

56.03%

|

|

Olanzapine

|

68

|

32.85%

|

|

Amisulpride

|

40

|

19.32%

|

|

Quetiapine

|

23

|

11.11%

|

|

Cariprazine

|

14

|

6.76%

|

|

Clozapine

|

14

|

6.76%

|

|

Haloperidol

|

9

|

4.34%

|

|

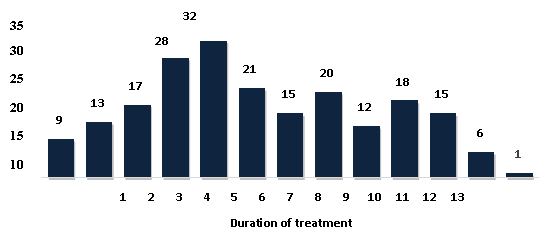

| Fig.

2: Duration of treatment |

Figure 2 depicts the

distribution of subjects according to the duration

of treatment.

Table 3 indicates

distribution of study subjects according to the

CPZ equivalent doses/day for current ongoing

antipsychotics.

| Table

3: Chlorpromazine Cumulative Equivalent Dose |

| Chlorpromazine Cumulative Equivalent

Dose |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

50

|

9

|

4.34

|

|

100

|

9

|

4.34

|

|

125

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

150

|

4

|

1.93

|

|

200

|

79

|

38.16

|

|

225

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

250

|

17

|

8.21

|

|

275

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

300

|

40

|

19.32

|

|

325

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

350

|

15

|

7.24

|

|

400

|

19

|

9.17

|

|

450

|

6

|

2.89

|

|

500

|

2

|

0.96

|

|

550

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

600

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

650

|

1

|

0.48

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

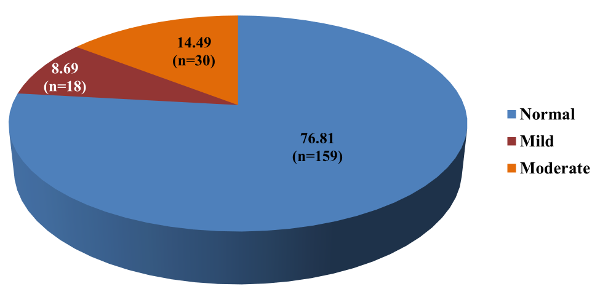

Figure 3 indicates

distribution of study subjects according to the

AIMS- facial and oral score. Out of 207 study

subjects, 18 (8.69%) had mild Tardive Dyskinesia

and 30 (14.49%) had moderate Tardive Dyskinesia.

|

Fig.

3: AIMS - facial and oral (N=207)

|

Overall prevalence

of Tardive Dyskinesia according to AIMS (facial

and oral) was 23.2%.

According to AIMS

(extremity) and AIMS (trunk) scores, none of the

207 subjects had TD.

Table 4 indicates

distribution of study subjects according to the

AIMS- global score and distribution of study

subjects according to the Schooler Kane criteria.

Out of 207 study subjects, 13 (6.28%) had mild

Tardive Dyskinesia and 20 (9.66%) had moderate

Tardive Dyskinesia.

Overall prevalence

of Tardive Dyskinesia according to AIMS (global)

score was 16%

Out of 207 study

subjects, 31 (14.5%) had mild Tardive Dyskinesia.

Overall prevalence of Tardive Dyskinesia according

to Schooler Kane criteria was 14.5%.

|

Table 4: AIMS - Global

|

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

Normal

|

174

|

84.05

|

|

Mild

|

13

|

6.28

|

|

Moderate

|

20

|

9.66

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

|

Schooler Kane criteria satisfied

|

|

Satisfied

|

31

|

14.49

|

|

Not satisfied

|

177

|

85.50

|

|

Total

|

207

|

100.00

|

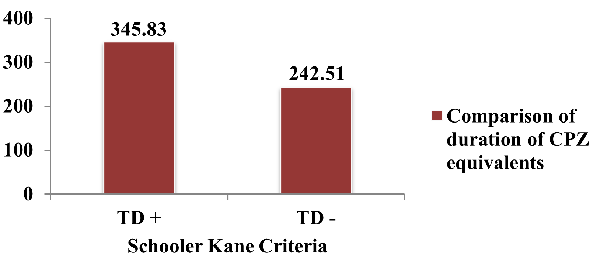

Figure 4 depicts

comparison of CPZ equivalent doses/day for current

ongoing antipsychotics according to Schooler Kane

criteria. The average CPZ equivalents among study

subjects who satisfied the Schooler Kane criteria

was 345.83 (±101.73) and the

average CPZ equivalents among study subjects who

did not satisfy the Schooler Kane criteria was

242.51 (± 96.88). The difference was statistically

significant (p<.001).

|

Fig.

4: Comparison of duration of

Chlorpromazine equivalents according to

the Schooler Kane criteria

|

Discussion:

Tardive dyskinesia

is a movement disorder which can occur due to the

use of antipsychotics. The oral, buccal, and

lingual regions of the face are often afflicted by

TD; while the trunk and limbs may also be

affected, they are typically less severely

affected. Athetoid or choreiform movements are

common terms used to characterise involuntary

movements. (8)

Women are more

likely than men to develop tardive dyskinesia,

particularly in patients who are middle-aged to

elderly. Patients who are elderly may be more

susceptible to tardive dyskinesia because of

age-related changes in the body and brain. (12)

Tardive dyskinesia

(TD) gets its name from the slow or tardive onset

of involuntary movements of the face, lips,

tongue, trunk, and extremities. A number of

theories have been put forth regarding the

mechanism, including the following: oxidative

stress, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) depletion,

cholinergic deficiency, prolonged blockade of

postsynaptic dopamine receptors resulting in

dopamine receptor hypersensitivity; altered

synaptic plasticity; neurotoxicity; and impaired

neuroadaptive signalling. (13)

In this study, the

majority of patients were in the 51–60 age range,

with an average age of 45.39 years (SD=12.6336)

(Table 1). This almost exactly matches the

findings of the study by Sahel Hemmati et al (14),

which revealed that the study's youngest and

oldest participants were, respectively, 19 and 60

years old. Half of the sample group had an average

age of 44 or less, according to the average, mean,

and standard deviation. This is consistent with

the research done by Daniel SJ et al (15), where

the sample's average age was 43.75 years (SD

10.5). This is consistent with the study by Bhatia

T et al (16), in which the mean age was 47.6±11.09

years.

Out of 207

participants in this study, 139 (67.1%) had

schizophrenia or an unexplained psychosis, and 68

(32.9%) had bipolar (Figure 1). This is consistent

with a research by Abdeta T et al (17), in which a

maximum of 79.5% of participants were diagnosed

with schizophrenia. This is almost in line with a

research by N Gatere et al(18), in which 48 people

(28.8%) had bipolar and 91 people (45%) had

schizophrenia or an unexplained psychosis. This

nearly matches the findings of the study by Bakker

PR et al,(19) which found that schizophrenia and

psychosis, as defined by DSM-IV Axis I, accounted

for 69.6% and 5.3%, respectively, of diagnoses.

Out of 207 study

participants, 116 utilized the drug Risperidone in

this study (Table 2). This almost matches the

findings of Bhatia T's(16) study. Among 96

patients with TD, Risperidone was the only

antipsychotic medication used in 39.6% of cases

and in 47.9% of cases. This is consistent with

research by Achalia RM et al(11), in which

Risperidone was the most often prescribed

antipsychotic (n = 50) for 90 individuals using

SGAs. This is consistent with the Santhanakrishna

et al study(20), in which 45.71% of patients

received Risperidone as their most frequent

prescription.

According to Bhatia

T et al,(16) atypical antipsychotic medications

are known to elicit extra- pyramidal symptoms less

frequently (only 1% of the time) and to be related

with milder TD than older, traditional

antipsychotic medications (5%). In a high-risk

group of elderly patients, Jeste DV et al(21) came

to the conclusion that Risperidone was

considerably less likely to cause TD than the

traditional neuroleptic medicines, at least over a

nine-month period.

A maximum of 32

study participants received treatment for 5 years

in this trial (Figure 2). According to a study by

Abdeta T et al,(17) 49% of participants took their

prescribed medications for more than five years.

This is consistent with the study of Assefa Kumsa

et al(22), in which 246 (60.0%) of the patients

had received treatment for an average of 4.8

years, with an SD of 3.9 years, ranging from 1 to

5 years.

Of the 207

participants in this study, 99 are urban dwellers,

and 111 are rural (Table 1).

This

contradicts research by Assefa Kumsa et al

(22), in which 206 study participants lived in

urban regions and 204 in rural areas. Out of 207

study participants, 71.5% were illiterate in this

study (Table 1). This contradicts a research by

Abdeta T et al (17), in which 42.4% of respondents

had educational status in grades 1-6.

In this study, 79

study participants received a cumulative

equivalent dose of 200 mg of Chlorpromazine (Table

5). According to a study by Abdeta T et al (17),

74.2% of the study individuals had a cumulative

equivalent dose of 100–<400 mg of

Chlorpromazine. This is almost in line with the

findings of the study by N Gatere et al (18), in

which 133 of the study individuals received less

than 500 mg of Chlorpromazine cumulative

equivalent dose each day. The average

Chlorpromazine-equivalent dose used in this

population in the past was 336.95, according to a

study by Woniak K et al.(23)

Hyperkinetic

choreiform involuntary motions that frequently

change in severity are referred to as dyskinesia.

TD was evaluated using the Abnormal Involuntary

Movement Scale (AIMS)(9) and the Schooler and Kane

criteria(10) were used to define the case. These

criteria required (i) the presence of moderate

dyskinesia in at least one body area or mild

dyskinesia in at least two body parts, and (ii)

the absence of other conditions that cause

abnormal involuntary movements.

Of the 207

participants in this study 18 (8.7%) had mild

Tardive Dyskinesia, and 30 (14.5%) had significant

Tardive Dyskinesia (Figure 3). Tardive Dyskinesia

affected 23.2% of people overall, according to

AIMS (facial and oral) score. This is consistent

with a study by Bakker PR et al,(19) which found

that the overall prevalence of tardive dyskinesia

for orofacial TD ranged from 21.7 to 32.5%.

According to the study done by O Gureje et al,(24)

the prevalence of orofacial involuntary movements

was 26% and was determined by an AIMS rating of 2

on any one orofacial area. According to the

research done by Anusa A,(25) mild Tardive

Dyskinesia affected 24 people (21.1%), whereas

moderate Tardive Dyskinesia affected 28 people

(24.5%). According to AIMS (extremity) score, none

of the study participants had TD of extremities.

This is approximately in line with the research

done by Anusa A et al, (25) where the maximum

percentage of subjects that met the study's goals

(extremity) was 68.4%.

According to AIMS –

trunk scores, none of the study participants had

truncal TD. This is almost in line with a study by

Bakker PR, (19) where the majority of individuals

were normal for limb truncal TD goals

(extremity).The average AIMS total score,

according to Bhatia T et al,(16) was 2.29±3.25

(6.29±3.48 for TD positive cases), whereas the

average orofacial score, average extremities

score, and average trunk score were each 0.53±1.29

(1.72±1.90 for TD positive cases) and 0.09±0.29

(0.32±0.47 for TD positive).

This is in contrast

to a study by Santhanakrishna et al (20), which

found that among extrapyramidal symptoms,

involvement of the extremities was most common in

42.5% of cases, followed by involvement of the

trunk in 35.7% of cases and of the face and mouth

in 21.42% of cases. In 45% of the patients, the

severity of the extrapyramidal symptoms was

moderate, while in 25.71% of the patients, it was

mild.

This study shows how

the study volunteers were distributed based on the

overall study goal score. 13 (6.3%) and 20 (9.7%)

of the 207 study participants had mild and

significant Tardive Dyskinesia, respectively

(Table 4). According to AIMS (global), 16% of

people worldwide had Tardive Dyskinesia. This is

in line with the research done by Abdeta T et al

(17), who found that 14.6% of participants in the

current study had TD, with a range of 10.76% to

18.4%. This almost matches the findings of the

study by Taye H et al.,(26) which found that 11.9%

of patients experienced TD and that the prevalence

of TD among psychiatric patients taking

first-generation antipsychotics is similar to

that. This is consistent with the research done by

Achalia RM et al.,(11) which found that 26.4% of

the sample overall had probable TD.

This study shows how

the study subjects were distributed using the

Schooler-Kane criteria (Table 4). 31 (14.5%) of

the 207 participants in the research exhibited

mild Tardive Dyskinesia. According to Schooler

Kane criterion, Tardive Dyskinesia by Woerner MG

et al(4), was present in 14.5% of people

nationwide. According to a research by Gatere et

al(18), 12% of participants had TD (as defined by

the Schooler Kane criteria). This is in contrast

to a research by Munshi T et al(27), where 29% of

participants met the Schooler Kane criteria for

TD.

In this study,

Chlorpromazine equivalents are compared using

Schooler-Kane criteria (Figure 4). According to

study subjects who met the Schooler Kane

requirements, the average Chlorpromazine

equivalents were 345.83 (±101.73), whereas those

who did not met the criterion had Chlorpromazine

equivalents of 242.51 (±96.88). There was a

statistically significant difference (p<.001).

This is consistent with the research done by

Wozniak K et al(23) in which the average

chlorpromazine-equivalent dose used in this

population in the past who met the Schooler Kane

requirements were 336.95.

Future studies could

include a bigger sample size. Studies could also

be done with patients who are followed up

longitudinally.

Strengths:

The strengths of

this study are that standard diagnostic criteria

and rating scales were used. A good sample size

was taken, involving both males and females. Also,

patients with chronic mental illness from two

rehabilitation centres were considered. A single

examiner has conducted the examination process,

eliminating inter-observer variability.

Limitations:

The limitation of

this study is that it is necessary to conduct

studies with sizable samples that are tracked over

long periods of time to confirm the results of the

current study.

Conclusion:

Many patients with

psychotic diseases experienced movement

difficulties brought on by conventional

antipsychotics, which were viewed as burdensome

and stigmatizing events. It was also discovered

that chlorpromazine comparable dosages were

significantly higher among participants with TD.

Orofacial TD had the highest overall prevalence.

Designing treatment guidelines, expanding the

availability of medications with minimum adverse

effects, and providing psychoeducation on related

aspects are crucial.

Funding: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Disclosure:

This paper has been presented at

KANCIPS and IPSOCON conferences 2023. It has

received the HS Subramanyam award for the best PG

oral paper.

References:

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM-5-TR)DSM. Available from: https://www.psychiatry.org:443/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- Glazer WM. Review of incidence studies of

tardive dyskinesia associated with typical

antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry.

2000;61 Suppl 4:15–20.

- Tarsy D, Baldessarini RJ. Epidemiology of

tardive dyskinesia: is risk declining with

modern antipsychotics? Mov Disord Off J Mov

Disord Soc. 2006 May;21(5):589–98.

- Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Saltz BL, Lieberman JA,

Kane JM. Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia

in the elderly: rates and risk factors. Am J

Psychiatry. 1998 Nov;155(11):1521–8.

- Jeste DV, Caligiuri MP, Paulsen JS, Heaton RK,

Lacro JP, Harris MJ, Bailey A, Fell RL, McAdams

LA. Risk of tardive dyskinesia in older

patients. A prospective longitudinal study of

266 outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

1995 Sep;52(9):756-65. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7654127/

- Correll CU, Schenk EM. Tardive dyskinesia and

new antipsychotics. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008

Mar;21(2):151–6.

- Woerner MG, Correll CU, Alvir JMJ, Greenwald

B, Delman H, Kane JM. Incidence of tardive

dyskinesia with risperidone or olanzapine in the

elderly: results from a 2-year, prospective

study in antipsychotic-naïve patients. Neuropsychopharmacol

Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011

Jul;36(8):1738–46.

- Mori Y, Takeuchi H, Tsutsumi Y. Current

perspectives on the epidemiology and burden of

tardive dyskinesia: a focused review of the

clinical situation in Japan. Ther Adv

Psychopharmacol. 2022 Dec

26;12:20451253221139608.

- Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for

psychopharmacology. Rev. 1976. Rockville, Md:

U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare,

Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and

Mental Health Administration, National Institute

of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research

Branch, Division of Extramural Research

Programs; 1976. 603 p.

- Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for

tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982

Apr;39(4):486–7.

- Achalia RM, Chaturvedi SK, Desai G, Rao GN,

Prakash O. Prevalence and risk factors

associated with tardive dyskinesia among Indian

patients with schizophrenia. Asian J

Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;9:31–5.

- Vasan S, Padhy RK. Tardive Dyskinesia. In:

StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls

Publishing; 2023. Available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448207/

- Cornett EM, Novitch M, Kaye AD, Kata V, Kaye

AM. Medication-Induced Tardive Dyskinesia: A

Review and Update. Ochsner J.

2017;17(2):162–74.

- Hemmati S, Astaneh AN, Solemani F, Vameghi R,

Sajedi F, Tabibi N. A survey of the tardive

dyskinesia induced by antipsychotic drugs in

patients with schizophrenia. Iran J

Psychiatry. 2010;5(4):159–63.

- Daniel SJ, Kannan PP, Malaiappan M, Anandan H.

Relationship between Awareness of Tardive

Dyskinesia and Awareness of Illness in

Schizophrenia. Int J Sci Stud.

2016;4(7):17-20

- Bhatia T, Sabeeha MR, Shriharsh V, Garg K,

Segman RH, Uriel HL, et al. Clinical and

familial correlates of tardive dyskinesia in

India and Israel. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50(3):167–72;

discussion 172.

- Abdeta T, Tolessa D, Tsega W. Prevalence and

Associated Factors of Tardive Dyskinesia Among

Psychiatric Patients on First-Generation

Antipsychotics at Jimma University Specialized

Hospital, Psychiatric Clinic, Ethiopia:

Institution Based on A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal

of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders

2019;3: 179-190. Available from: http://www.fortunejournals.com/articles/prevalence-and-associated-factors-of-tardive-dyskinesia-among-psychiatric-patients-on-firstgeneration-antipsychotics-at-jimma-univ.html

- Gatere N, Othieno CJ, Kathuku DM. Prevalence

of tardive dyskinesia among psychiatric

in-patients at Mathari Hospital, Nairobi.

East Afr Med J. 2002 Oct;79(10):547–9.

- Bakker PR, de Groot IW, van Os J, van Harten

PN. Long-stay psychiatric patients: a

prospective study revealing persistent

antipsychotic-induced movement disorder. PloS

One. 2011;6(10):e25588.

- Santhanakrishna KR, Revanakar S,

Srirangapattna C. Prevalence of Extrapyramidal

Side Effects in Patients on Antipsychotics Drugs

at a Tertiary Care Center5. J Psychiatry.

2017;20(5). Available from: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/prevalence-of-extrapyramidal-side-effects-in-patients-on-antipsychotics-drugsat-a-tertiary-care-center5-2378-5756-1000419.php?aid=92481

- Jeste DV, Lacro JP, Bailey A, Rockwell E,

Harris MJ, Caligiuri MP. Lower incidence of

tardive dyskinesia with risperidone compared

with haloperidol in older patients. J Am

Geriatr Soc. 1999 Jun;47(6):716–9.

- Kumsa A, Girma S, Alemu B, Agenagnew L.

Psychotropic Medications-Induced Tardive

Dyskinesia and Associated Factors Among Patients

with Mental Illness in Ethiopia. Clin

Pharmacol. 2020 Dec 1;12:179-187. doi:

10.2147/CPAA.S285585. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33293875/

- Woźniak K, Kłoszewska I. Clinical assessment

of antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms

in nursing home residents with schizophrenia. Psychiatr

Psychol Klin. 2016 Mar 31;16(1):7–14.

- Gureje O. Topographic subtypes of tardive

dyskinesia in schizophrenic patients aged less

than 60 years: relationship to demographic,

clinical, treatment, and neuropsychological

variables. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988

Dec;51(12):1525–30.

- Anusa AM, Thavarajah R, Nayak D, Joshua E, Rao

UK, Ranganathan K. A Study on Drug-Induced

Tardive Dyskinesia: Orofacial Musculature

Involvement and Patient’s Awareness. J

Orofac Sci. 2018;10(2):86–95.

- Taye H, Ebrahim J. Antipsychotic Medication

Induced Movement Disorders: The Case of Amanuel

Specialized Mental Hospital, Addis Ababa,

Ethiopia. Am J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2014

Jan 1;2:76.

- Adam UU, Husain N, Haddad PM, Munshi T, Tariq

F, Naeem F, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in a South

Asian population with first episode psychosis

treated with antipsychotics. Neuropsychiatr

Dis Treat. 2014 Oct 14;10:1953–9.

|