|

Introduction

The

physical growth and nutritional status of an

individual and/or a community plays a critical

role in maintaining optimal health and well being.

Adequate nutrition is essential for growth,

development and the prevention of various chronic

diseases. [1] Understanding and assessing the

physical growth and nutritional status of

population is crucial for implementing effective

public health interventions and designing targeted

strategies to address nutritional deficiencies.

Nutritional status refers to the overall status of

an individual’s health as influenced by their

dietary intake and nutritional well-being. Optimal

nutritional status is essential for the

maintenance of physiological functions, immune

system integrity, and the prevention of

nutrition-related diseases.[2]

The

intake of recommended amounts of nutrients during

childhood or adolescence is necessary for growth.

Good nutrition is an essential need for children's

health development, well-being, learning, physical

fitness and the ability to withstand stress and to

function at optimum productivity.[3] Numerous

studies have demonstrated the significant impact

of nutritional status on health outcomes across

different life stages. Inadequate nutritional

intake and imbalances in essential nutrients can

lead to malnutrition (both under and over

nutrition), which is associated with increased

susceptibility to infections, impaired growth and

development, and higher mortality rates,

particularly among children. [4-5]

Accurate

assessment of nutritional status is essential for

identifying individuals and populations at risk of

malnutrition or specific nutrient deficiencies.

Anthropometric measurements, including body mass

index (BMI), waist circumferences, and skin fold

thickness are commonly used to evaluate overall

body composition and identify under nutrition or

obesity. [6]

In India, recent

Comprehensive National Nutritional Survey (CNNS)

2016-2018 among the children from birth to 19

years showed that adverse nutritional status of

children is not only restricted to the prevalence

of under nutrition but also to over nutrition as

India is passing through double burden of

malnutrition. [7] The studies of nutritional

status among children and adolescent using

anthropometric measures, have been conducted in

different Northeast Indian tribes for the last two

decades but only few have been reported from

Arunachal Pradesh. [8 -15] This state having

around 26 distinct major tribes with numerous

minor or lesser known tribes is less studied in

term of nutritional status of the children. While

the nation has developed its public health

policies to crop off the double burden of

nutrition, the state is yet to develop a baseline

data to represent the nutritional status of

various major and minor communities. Therefore,

this study was conceptualized to assess the

physical growth and nutritional status using

anthropometric measures and index in the Apatani

and Nyishi tribal children aged five to fifteen

years and compare the two populations living in a

similar ecological setting in Lower Subansiri and

Kamle districts of Arunachal Pradesh.

Methods

Area of Study

The present

cross-sectional study was conducted among the

Apatani tribe of Ziro valley, Lower Subansiri

district and Nyishi tribe of Raga, the headquaters

of Kamle district, Arunachal Pradesh, India. The

data was collected from 12th January to

28th February 2023.

Sample size

and sample selection

The total number of

participants was 442 children from two different

tribal groups (Apatani 231 and Nyishi 211) aged 5

to 15 years. The data were collected using

purposive sampling due to the different terrain of

settlements of the studied households, which

created operational difficulties. Besides,

unavailability and unwillingness from the

participants was another cause for not using

appropriate statistical sampling. However, with

respect to the selection of households and

interviewees, an attempt was made to cover all

those households, whose members were willing to

cooperate in the study, where written consent was

also collected from their parents. The data of the

Apatani samples were collected from several

villages of Ziro valley, Lower Subansiri district

such as Bulla, Siibey, Hari, Hija, Hong,

Bamin-Michi and Dutta and data of Nyishi sample

were collected from several villages of Raga,

Kamle district such as Yada I, Yada II, main Raga

and Raga II. The study was approved by the

Institutional Ethical Committee of Rajiv Gandhi

University, Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Age

estimation

It may be mentioned

that great difficulties were experienced in the

assessment of age, especially from the Raga

headquarter due to their illiteracy and lack of

any written records. Even parents were not aware

of their children’s age. Consequently, in these

cases, estimation of age was done through

referencing to some important local events

(horoscope, flood, storm, festivals etc.) and to

the known age of some individuals who seemed to be

in the same age group and some was ascertained

from birth certificates and official school

records. Thus, in this connection, there could be

some error in the estimation of age.

Socio-economic

data

A pre-tested and

pre-structured scheduled questionnaire was used to

collect some of the socio-economic data including

age, sex and number of parity. Besides, a detailed

ethnographic profile of the two studied

communities was also collected from the field for

general description of the population.

Anthropometric

measurements

The anthropometric

measurements of height (cm), weight (kg), waist

circumference (cm), hip circumference (cm) and mid

upper arm circumference (MUAC), were collected

using standard technique and instruments.

Anthropometer rod was used to collect height (cm)

with a measuring error 0.1 cm, a portable weighing

machine was used to collect weight nearest to 0.5

kg deviation. All circumference measurements were

taken using measuring tape. For height and weight,

the children were wearing light cloths and

standing in anatomical positions with bare feet

and horizontal planes. For circumferences the

cloths were lifted up. [16]

Data

analysis

To assess the

nutritional status of the studied Apatani and

Nyishi children aged 5 to 15 years, a single

anthropometric measure of Body Mass Index (BMI)

was used for obvious operational benefit. BMI was

calculated by using the formula [BMI = weight (kg)

/ height (m2)]. After calculating the

BMI, age and sex matched graded international cut

–off points were used for getting undernutrition

and overnutrition prevalence as per classification

proposed by Cole et al. [17,18]

Statistical

Analysis

Age and sex- wise

descriptive statistics like arithmetic mean,

standard deviation and standard error of mean was

calculated for all the anthropometric measures.

Contingency Χ2 test was used to assess

the association between communities under study

and nutritional status. Bivariate logistic

regression was performed to identify the selected

significant factors associated with overweight and

obese children who were coded as 1 in comparison

to their counterparts coded as 0 for logistic

regression analysis. All the analyses were done

using SPSS 16.0 version and MS Excel 2000.

Brief

description of the population

The Apatani

The Apatani,

designated as a scheduled tribal group, comprising

of approximately 25,000 individuals, live in Ziro

Valley/ Apatani Valley in the Lower Subansiri

district of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Their

language belongs to the Sino-Tibetian family. The

Apatani has a rich oral tradition and hardly any

written records. The inhabitants of the Apatani

valley constitute a community distinct in

language, dress and distinct manner of living. The

Apatanis are mainly agriculturists. This tribe

practices wet rice cultivation, choosing to

permanently settle rather than live a nomadic

lifestyle that comes with slash-and-burn type of

cultivation. This type of cultivation is unique to

the Apatanis. Taking the sustainability of their

fields a step further, the tribe also harvests

fish in the wet fields alongside rice. This

instantly doubles the food production of their

field. The Apatanis have had an intricate

irrigation system of canals and channels from the

time they started wet rice cultivation. Along with

agriculture, the others are engaged in poultry,

hunting and fishing. The people also rear cattle,

pig and goats. The Apatani women are also skilful

weavers. The women collect the firewood for the

household from the woods. They also go to the

nearby food market to sell their agricultural

products. Basketry is a popular handicraft among

the man folk. In recent years, there has been an

increase in white-collar jobs with many of them

engaged as government employees, doctors,

engineers and other modern professionals.

The Nyishi

The Nyishi is the

largest tribal group of Arunachal Pradesh in

India. The word Nyishi is the combination of two

words ‘Nyi’ means ‘a human’ and the word ‘shi’

denotes ‘highlands’. They are spread across eight

districts of Arunachal Pradesh viz., Kra-Daadi,

Kurung Kumey, Papum Pare, East Kameng, West

Kameng, Kamle, Pakke Kessang and parts of Lower

Subansiri district. The presently studied Nyishi

children live in Kamle district. Nyishi speak the

Tibeto-Burman language of the Sino-Tibetan family.

There’s no script yet. Like many other tribes,

they have a rich oral tradition of folklore,

tribal history, and folk wisdom. Whatever is known

of them is passed from generation to generation

through oral traditions. Nyishi food choices

revolve around their agricultural produce viz.

rice, millet, maize, and yams. Rice is the staple

food that is supplemented by meat and vegetables.

They consume boiled food mostly. The meat is

boiled with a little salt in it. No oil or spices

are used. It’s garnished with leafy vegetables and

grated ginger. Sometimes, the meat is roasted or

smoke-dried and kept in bamboo baskets to preserve

it for future use. Bamboo shoots are used to add

flavor to the food. They are particularly fond of

smoked meat.

Results

The arithmetic means

and standard deviations of anthropometric measures

and BMI for both the Apatani and the Nyishi boys

aged 5 to 15 years are shown in Table 1. The

height (cm), weight (kg), waist circumference

(cm), hip circumference (cm) and mid upper arm

circumference (cm) showed a gradual increase over

the age. However, the BMI (kg/m2)

showed fluctuating growth pattern. The maximum

height difference (10.34 cm) between two

successive age groups was found between 12 and 13

years of age among the Apatani boys and 11 and 12

years (8.95 cm of height differences) among the

Nyishi boys. In case of weight measure, the

maximum weight difference (5.56 kg) between two

successive age groups was observed between 11 and

12 years of age among the Apatani boys and 11 and

12 years (5.13 kg of weight differences) among the

Nyishi boys. Rest of the anthropometric measures

showed similar kind of increasing trends among

both the Apatani and Nyishi boys.

|

Table 1: Mean and standard deviation of

anthropometric measures among Apatani and

Nyishi boys

|

|

Age in years

|

N

|

Height (cm)

|

Weight (kg)

|

Waist Cir (cm)

|

Hip Cir. (cm)

|

MUAC (cm)

|

BMI (kg/m2)

|

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

|

Apatani

|

|

5

|

17

|

104.00±6.82

|

17.00±2.57

|

51.53 ±2.60

|

51.76±3.21

|

17.12±1.17

|

15.67 ±1.12

|

|

6

|

13

|

111.35±5.15

|

18.56±3.54

|

51.92 ±3.17

|

54.00±3.14

|

17.92±0.86

|

14.96 ±2.39

|

|

7

|

12

|

120.00±6.32

|

23.93±4.19

|

56.67 ±5.45

|

58.00±5.75

|

18.17±1.95

|

16.57 ±2.30

|

|

8

|

20

|

123.98±4.95

|

24.49±2.92

|

56.90 ±4.58

|

58.70±4.11

|

18.95±1.15

|

15.93 ±1.63

|

|

9

|

13

|

128.69±4.35

|

27.64±5.00

|

59.00 ±8.77

|

60.62±5.84

|

19.54±1.98

|

16.66 ±2.67

|

|

10

|

11

|

135.00±9.14

|

31.55±5.35

|

61.67 ±7.03

|

64.17±4.12

|

19.50±1.97

|

18.44 ±4.41

|

|

11

|

6

|

135.00±8.79

|

34.01±5.23

|

64.22 ±6.37

|

66.27±7.63

|

21.64±2.69

|

17.21 ±1.70

|

|

12

|

9

|

144.33±6.93

|

39.57±9.15

|

65.82 ±7.49

|

67.33±7.28

|

21.89±2.47

|

18.88 ±3.36

|

|

13

|

9

|

154.67±6.56

|

43.81±9.14

|

66.56 ±8.35

|

72.89±9.88

|

22.11±1.76

|

18.12 ±2.04

|

|

14

|

3

|

158.67±7.09

|

44.33±6.66

|

65.00 ±2.00

|

71.00±3.20

|

22.00±2.65

|

17.55 ±1.54

|

|

15

|

9

|

161.11±3.18

|

46.81±8.15

|

66.78 ±4.24

|

73.33±5.51

|

23.00±1.94

|

17.99 ±2.75

|

|

Nyishi

|

|

5

|

13

|

104.31±5.33

|

17.08±2.56

|

52.62 ±2.81

|

52.08±2.43

|

16.00±1.08

|

15.67 ±1.88

|

|

6

|

6

|

110.17±4.71

|

18.83±3.76

|

53.67 ±3.61

|

52.50±2.17

|

16.17±1.17

|

15.38 ±2.13

|

|

7

|

13

|

113.54±6.50

|

20.92±3.62

|

55.54 ±5.11

|

54.38±3.57

|

17.15±1.63

|

16.13 ±1.65

|

|

8

|

11

|

120.27±4.24

|

23.27±2.72

|

55.45 ±3.39

|

57.18±2.96

|

17.18±0.98

|

16.04 ±1.18

|

|

9

|

14

|

126.43±8.49

|

26.86±6.97

|

58.14 ±4.76

|

60.21±4.77

|

17.79±1.58

|

16.54 ±2.59

|

|

10

|

17

|

128.18±6.61

|

26.29±4.36

|

58.29 ±4.43

|

59.06±4.63

|

18.12±1.80

|

15.98 ±2.29

|

|

11

|

13

|

132.69±4.70

|

30.69±6.14

|

63.23 ±5.96

|

63.85±5.34

|

18.92±1.80

|

17.31 ±2.42

|

|

12

|

11

|

141.64±9.44

|

35.82±8.04

|

63.91 ±5.03

|

67.36±7.00

|

20.00±1.95

|

17.66 ±1.90

|

|

13

|

7

|

145.86±8.48

|

38.00±8.70

|

64.14 ±3.76

|

69.00±5.92

|

20.71±1.98

|

17.61 ±2.27

|

|

14

|

9

|

147.89±4.34

|

41.78±5.70

|

64.11 ±2.98

|

69.78±3.67

|

21.33±1.94

|

19.03 ±1.68

|

|

15

|

4

|

153.50±6.03

|

43.50±8.35

|

66.00 ±6.00

|

67.50±7.94

|

21.75±2.75

|

18.43 ±3.08

|

The arithmetic means

and standard deviations of anthropometric measures

and BMI for both the Apatani and Nyishi girls aged

5 to 15 years are shown in Table 2. Like boys, the

height (cm), weight (kg), waist circumference

(cm), hip circumference (cm) and mid upper arm

circumference (cm) showed a gradual increase over

the age among the girls. However the BMI (kg/m2)

showed fluctuating growth pattern. The maximum

height difference (7.37 cm) between two successive

age groups was found between 9 and 10 years of age

among the Apatani girls and 10 and 11 years (10.50

cm of height differences) among the Nyishi girls.

In case of weight measure, the maximum weight

difference (5.82 kg) between two successive age

groups was observed between 10 and 11 years of age

among the Apatani girls and 9 and 10 years (7.53

kg of weight differences) among the Nyishi girls.

Rest of the anthropometric measures showed similar

kind of increasing trends among both the Apatani

and Nyishi girls.

|

Table 2: Mean and standard deviation of

anthropometric measures among Apatani and

Nyishi girls

|

|

Age in years

|

n

|

Height (cm)

|

Weight (kg)

|

Waist Cir (cm)

|

Hip Cir. (cm)

|

MUAC (cm)

|

BMI (kg/m2)

|

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

Mean ± SD

|

|

Apatani

|

|

5

|

16

|

108.38±8.83

|

16.32±2.86

|

52.13±3.20

|

52.31±2.80

|

16.69±1.40

|

15.28 ±1.55

|

|

6

|

12

|

112.83±5.42

|

20.43±3.99

|

55.83±6.21

|

57.00±4.16

|

18.00±1.21

|

15.99 ±2.63

|

|

7

|

15

|

119.40±5.79

|

21.00±1.70

|

52.93±3.26

|

55.93±2.89

|

17.67±1.40

|

14.77 ±1.37

|

|

8

|

11

|

126.91±4.28

|

27.90±9.19

|

57.45±7.27

|

61.55±6.27

|

19.18±1.94

|

17.15 ±4.81

|

|

9

|

8

|

130.63±7.31

|

27.84±5.05

|

58.13±7.81

|

61.63±7.11

|

19.63±2.39

|

15.76 ±2.19

|

|

10

|

13

|

138.00±7.19

|

29.09±6.01

|

56.54±7.71

|

62.85±6.96

|

19.85±1.68

|

15.14 ±2.08

|

|

11

|

9

|

141.67±7.35

|

34.91±6.99

|

56.43±9.54

|

66.00±5.48

|

20.29±1.60

|

16.95 ±2.05

|

|

12

|

7

|

142.86±7.60

|

37.97±9.04

|

63.00±6.32

|

68.00±8.37

|

22.44±2.24

|

18.71 ±2.83

|

|

13

|

7

|

147.25±8.97

|

41.36±7.42

|

61.25±5.19

|

69.50±1.29

|

22.29±3.04

|

20.43 ±3.59

|

|

14

|

4

|

150.43±7.41

|

46.12±8.00

|

68.14±9.41

|

73.29±9.53

|

22.50±1.73

|

18.97 ±1.59

|

|

15

|

7

|

149.71±3.99

|

45.55±4.55

|

69.43±6.92

|

77.14±6.36

|

23.71±1.50

|

20.32 ±1.98

|

|

Nyishi

|

|

5

|

15

|

108.53±4.12

|

16.80±1.86

|

52.80±2.83

|

51.13±2.17

|

16.40±0.98

|

15.63±1.04

|

|

6

|

7

|

111.71±1.60

|

18.86±1.57

|

53.71±3.15

|

53.86±1.77

|

16.43±0.79

|

15.13±1.41

|

|

7

|

12

|

117.42±6.02

|

21.33±3.47

|

56.08±3.15

|

56.33±2.84

|

17.00±0.95

|

15.38±1.47

|

|

8

|

11

|

118.82±5.19

|

22.45±3.86

|

53.82±4.05

|

56.36±3.67

|

16.73±1.10

|

15.82±1.83

|

|

9

|

11

|

123.18±6.00

|

23.36±4.43

|

56.73±5.87

|

58.18±4.51

|

17.45±1.86

|

15.31±2.10

|

|

10

|

9

|

130.00±5.87

|

30.89±6.49

|

58.50±3.87

|

63.56±7.43

|

19.22±2.49

|

18.09±2.16

|

|

11

|

4

|

140.50±5.26

|

34.50±5.51

|

60.78±7.74

|

64.50±5.45

|

19.75±2.36

|

17.38±1.58

|

|

12

|

4

|

142.00±5.89

|

38.50±5.92

|

66.50±3.70

|

71.25±4.57

|

21.50±0.58

|

19.04±2.18

|

|

13

|

9

|

146.33±2.60

|

40.00±4.20

|

66.78±8.00

|

70.50±3.62

|

22.33±1.58

|

20.09±2.49

|

|

14

|

6

|

146.17±5.78

|

43.11±6.17

|

66.00±4.60

|

73.56±9.30

|

21.67±1.51

|

18.85±2.85

|

|

15

|

5

|

146.00±9.03

|

43.40±6.39

|

68.60±6.26

|

74.20±9.58

|

22.00±2.92

|

20.10±4.08

|

Table 3 shows the

mean differences of various anthropometric

measurements between Apatani and Nyishi boys and

girls, separately. In most of the ages, Apatani

boys were observed as heavier, taller, with higher

value of other anthropometric measures as compared

to Nyishi boys. Similarly, Apatani girls were

observed as heavier, taller, with higher value of

other anthropometric measures as compared to

Nyishi girls. The differences of anthropometric

measures in both the boys and girls were

statistically significant (p<0.05; p<0.01)

between the ages 8 and 10 years.

|

Table 3:Test of significance of

anthropometric measures among Apatani and

Nyishi boys and girls

|

|

Age in years

|

Height (cm)

|

Weight (kg)

|

Waist Cir. (cm)

|

Hip Cir. (cm)

|

MUAC (cm)

|

BMI (kg/m2)

|

|

Boys

|

|

5

|

0.134

|

0.078

|

1.094

|

0.292

|

2.684*

|

0.009

|

|

6

|

0.475

|

0.152

|

1.067

|

1.053

|

3.697**

|

0.373

|

|

7

|

2.515*

|

1.927

|

0.534

|

1.905

|

1.417

|

0.561

|

|

8

|

2.091*

|

1.138

|

0.916

|

1.708

|

4.313**

|

0.197

|

|

9

|

0.861

|

0.334

|

0.319

|

0.196

|

2.550*

|

0.121

|

|

10

|

2.295*

|

2.768*

|

2.637*

|

3.125**

|

4.159**

|

1.939

|

|

11

|

0.756

|

0.293

|

0.503

|

0.130

|

0.631

|

0.092

|

|

12

|

0.713

|

0.976

|

0.089

|

0.009

|

1.913

|

1.025

|

|

13

|

1.594

|

1.288

|

0.706

|

0.917

|

1.492

|

0.473

|

|

14

|

3.335**

|

0.742

|

0.475

|

1.300

|

0.477

|

1.340

|

|

15

|

3.048*

|

0.671

|

0.271

|

1.713

|

0.950

|

0.258

|

|

Girls

|

|

5

|

0.053

|

0.548

|

0.620

|

1.305

|

0.657

|

0.740

|

|

6

|

0.527

|

0.991

|

0.836

|

1.885

|

3.068**

|

0.798

|

|

7

|

0.869

|

0.327

|

2.530*

|

0.360

|

1.409

|

1.106

|

|

8

|

3.989**

|

1.812

|

1.449

|

2.365*

|

3.647**

|

0.857

|

|

9

|

3.094**

|

2.050

|

0.447

|

1.294

|

2.230*

|

0.456

|

|

10

|

2.757*

|

0.668

|

1.260

|

0.229

|

0.750

|

3.222**

|

|

11

|

0.284

|

0.703

|

1.300

|

0.758

|

1.970

|

0.870

|

|

12

|

0.193

|

0.860

|

1.990

|

1.613

|

1.434

|

1.595

|

|

13

|

1.552

|

0.851

|

0.314

|

0.570

|

0.041

|

0.219

|

|

14

|

0.220

|

0.375

|

1.523

|

0.522

|

0.810

|

0.074

|

|

15

|

0.997

|

0.458

|

0.168

|

0.644

|

1.344

|

0.126

|

| *p<0.05; **p<0.01 |

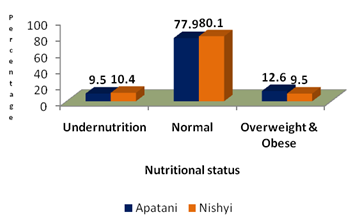

Table 4 shows

community-wise percentage distribution of

nutritional status based on BMI for age among the

studied boys and girls. It was observed that more

than 70% boys from Apatani and Nyishi communities

and more than 80% girls from those respective

communities had normal nutritional status. Overall

percentage of under nutrition was slightly higher

among the Nyishi children (10.4%) compared to the

Apatani children (9.5%) as shown in Figure 1. On

the other hand, the percentage of overweight and

obese children among the Apatani group (12.6%) was

little bit higher than their Nyishi counterparts

(9.5%). In spite of that, boys of both the

communities showed slightly higher percentages of

overweight and obesity compared to their girl

counterparts. However, in both the occasions, the

differences between gender and community-wise

distribution of nutritional status were not

statistically significant (p>0.05).

|

Table 4: Community-wise percentage

distribution of nutritional status (BMI

for age) among the studied boys and girls

|

|

Community

|

Nutritional status

|

Total n(%)

|

|

Undernutrition n(%)

|

Normal n(%)

|

Overweight and obese n(%)

|

|

Boys

|

|

Apatani

|

14 (11.47%)

|

89 (72.95%)

|

19 (15.57%)

|

122 (100.0%)

|

|

Nyishi

|

14 (11.86%)

|

91 (77.11%)

|

13 (11.01%)

|

118 (100.0%)

|

|

Total

|

28 (11.66%)

|

180 (75.0%)

|

32 (13.33%)

|

240 (100.0%)

|

|

Chi-square value

|

1.081, p>0.05

|

|

Girls

|

|

Apatani

|

8 (7.33%)

|

91 (83.48%)

|

10 (9.17%)

|

109 (100.0%)

|

|

Nyishi

|

8 (8.60%)

|

78 (83.87%)

|

7 (7.53%)

|

93 (100.0%)

|

|

Total

|

16 (7.92%)

|

169 (83.66%)

|

17 (8.41%)

|

202 (100.0%)

|

|

Chi-square value

|

0.264, p>0.05

|

|

| Figure 1:

Distribution of Nutritional status among

the Apatani and Nyishi children under

study |

Table 5 depicts the

binary logistic regression analysis of community,

sex and number of live births on overweight and

obese children under study. In this analysis, the

gender and communities were merged as there was

insignificant differences of nutritional status

between parameters. It was found that the Apatani

children were 1.383 times more likely to have

overweight and obesity compared to Nyishi

children. Besides, boys were 1.690 times more

likely to be overweight and obese than girls and

finally children of those families who had ≤ 3

number of live births were observed to have higher

chance of overweight and obesity than those with

more number of children.

|

Table 5: Binary logistic regression

analysis of community, sex and number of

live birth on overweight and obese

children under study

|

|

Variables

|

B

|

S.E.

|

Wald

|

df

|

Sig.

|

Exp (B)

|

95.0% C.I. for Exp (B)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lower

|

Upper

|

|

Apatani (Nyishi – Ref.)

|

0.324

|

0.326

|

0.985

|

1

|

0.321

|

1.383

|

0.729

|

2.621

|

|

Boys (Girls- Ref)

|

0.525

|

0.318

|

2.723

|

1

|

0.099

|

1.690

|

0.906

|

3.153

|

|

No. of Live Birth ≤ 3 (> 3 – Ref.)

|

0.030

|

0.333

|

0.008

|

1

|

0.928

|

1.031

|

0.536

|

1.981

|

|

Constant

|

-2.590

|

0.343

|

57.187

|

1

|

0.000

|

0.075

|

|

|

Ref.- Reference group

|

Discussion

This study presents

a glimpse of physical growth patterns and

nutritional status using anthropometric measures

and index of the Apatani and the Nyishi children

aged 5-15 years who live in a similar geographical

hilly terrain (Ziro at Lower Subansiri and Raga at

Kamle districts). Analysis of various

anthropometric measurements (height, weight, WC,

HC, MUAC) and BMI of both the populations revealed

that the mean values of different body

measurements represent an increasing trend with

the advancement of age. The study shows that the

Apatani children are significantly taller and

heavier during pre-adolescent stage compared to

the Nyishi children of both the sexes. A study on

urban Meitei children and adolescents of Manipur

in northeast India also showed that height and

body weight increase along with the advancing of

age in both boys and girls. [19]

It is also evident

from the present study that there was a variation

in both undernutrition and overnutrition

prevalence amongst pre-adolescents and adolescent

children (boys and girls) aged 5 to 15 years among

both the tribes. Comparatively, Nyishi children

had higher prevalence of undernutrition compared

to the Apatani children. In contrast, the Apatani

children had higher prevalence of

overweight/obesity compared to Nyishi children.

Similar kind of studies had been reported by

Asghar et al., where there was significant

variation in both the undernutrition and

overweight prevalence amongst pre-adolescent and

adolescent children among the Sartang and Miji

tribal children aged 5 to 18 years.[8] From the

bivariate logistic regression analysis, the

Sartang children were significantly more than two

times likely to be overweight compared to Miji

counterparts.[8] In the present study, the Apatani

children were 1.383 times more likely to be

overweight and obese compared to Nyishi children,

although the differences were not statistically

significant.

It was found during

the ethnographic fieldwork that Apatani children

were more modernized in their lifestyle and

consumed fast food, had better medical and

educational facilities and exposure to urban

culture than their counterparts among Nyishi

children. It was evident that traditional food

pattern among the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh had

been changed a lot due to globalization.[20]

Therefore, in-depth study of dietary

pattern, physical activity level and morbidity

pattern may be the major limitation of the present

study.

Immunization is one

of the important factors related to nutritional

status of children. The immunization status of the

studied children showed that the percentage of

complete doses of immunization was higher among

the Apatani group (87.01%) compared to Nyishi

group (36.97%) (Not shown in the table). This was

due to lack of awareness among the Nyishi

populations of Raga, Kamle district. In other

words, the majority of the Nyishi children were

born in home and less immunized (63.03%) compared

to National averages. [21] They

do not consider immunization of children as

important and also do not have good medical

facility. In contrast, Apatani population was well

aware of it and had better medical facility than

that of Nyishi population. A micro level regional

study among the Aka boys aged 9 to 18 years in

Arunachal Pradesh showed them to be comparatively

overweight (1.67%) than the present children. [22]

Conclusion

There are some

notable differences between the children of

Apatani and the Nyishitwo tribes in terms of the

mean values of anthropometric measures; the

Apatani children are taller and heavier compared

to the Nyishi counterparts and Nyishi children

have higher values of undernutrition compared to

Apatani children. This suggests that a greater

proportion of Nyishi children in the studied

population are experiencing undernutrition, which

can have detrimental effects on their growth and

development. Addressing undernutrition should be a

priority for policy makers, with a focus on

providing adequate nutrition and healthcare

interventions for Nyishi children. On the other

hand, a larger proportion of Apatani children in

the studied population are overweight or obese,

which can increase the risk of various health

issues such as cardiovascular diseases and

diabetes in their early age. This data can be

useful for policy makers as it highlights the need

for targeted interventions to address both

undernutrition and overweight/obesity among

children in these tribes. Policies should be

developed to improve access to nutritious food,

healthcare facilities, and education on balanced

diets for Nyishi children to combat

undernutrition. Similarly, policies should also

focus on promoting healthy eating habits, physical

activity, and awareness about the risks associated

with overweight/obesity among Apatani children.

However further study is also required to identify

the factors responsible for this disparity between

Apatani and Nyishi children.

Declaration of Conflicting

Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of

interest concerning this article's research,

authorship, and publication.

Funding sources:

None

Acknowledgments:

The authors are thankful to the participants of

the present study and also thankful to Rajiv

Gandhi University, Arunachal Pradesh, India for

Financial and logistic support.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Physical

status. The use and interpretation of

anthropometry. WHO Technical Report No. 854.

Geneva: WHO, 1995.

- Calder PC, Carr AC, Gombart AF, Eggersdorfer

M. Optimal nutritional status for a

well-functioning immune system is an important

factor to protect against viral infections.

Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):1181.

doi:10.3390/nu12041181.

- Lassi Z, Moin A, Bhutta Z. Nutrition in Middle

Childhood and Adolescence. In: Bundy DAP, Silva

Nd, Horton S, et al., editors. Child and

Adolescent Health and Development. 3rd edition.

Washington (DC): The International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank;

2017. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0423-6_ch11

- Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP et al.

Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight

in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet.

2013;382: 427–451. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X

- Fan Y, Yao Q, Liu Y, Jia T, Zhang J, Jiang E.

Underlying causes and co-existence of

malnutrition and infections: an exceedingly

common death risk in cancer. Front Nutr.

2022; 9:814095. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.814095

- Piqueras P, Ballester A, Durá-Gil JV,

Martinez-Hervas S, Redón J, Real JT.

Anthropometric indicators as a tool for

diagnosis of obesity and other health risk

factors: a literature review. Front Psychol.

2021; 12:631179. doi:

10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631179

- CNNS. Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey

- Birth to Adolescence Arunachal Pradesh

Factsheet 2018. Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, Government of India, 2018.

- Asghar Md, Amung R, Chakrabarty S. Nutritional

status of children (5-18 years) by using

Anthropometric indices: A cross-sectional study

among the Sartang and Miji, lesser known tribes

of Arunachal Pradesh, India. J Nepal Paediatr

Soc. 2021; 41(3):413-418.

- Singh MS, Devi RKN. Nutritional Status among

the Urban Meitei Children and Adolescents of

Manipur, Northeast India. J Anthropol. 2013:

1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/983845

- Longkumar T. Physical Growth and Nutritional

Status among Ao Naga Children of Nagaland,

Northeast India. J Anthropol. 2013:

1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/291239

- Khongsdier R, Mukherjee N. Growth and

nutritional status of Khasi boys in Northeast

India relating to exogamous marriages and

socioeconomic classes. Am J Phys Anthropol.

2003; 122(2):162-170.

- Sikdar M. Nutritional status among the Mising

tribal children of northeast india with respect

to their arm fat area and arm muscle area. Hum

Biol Rev. 2012; 1(4): 331-341.

- Maken T, Verte LR. Nutritional status of

children as indicated by z-scores of the Hmars:

A tribe of N.E. India. Antrocom: Online J

Anthropol. 2012; 8(1): 213-27.

- Saha S, Roy S, Sil SK. Physical growth and

nutritional status of Chakma tribal children of

tripura. Studies in Tribes and Tribals.

2017; 15(1): 18-22.

- Sil SK, Saha S, Roy S, Sarkar SR. Nutritional

status of urban Tripura tribal boys of Agartala,

Tripura. The Anthropologist. 2012;

14(2): 167-9.

- Weiner JS, Lourie JA. Practical Human Biology.

Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1981.

- Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH.

Establishing a standard definition for child

overweight and obesity worldwide: International

survey. BMJ. 2000; 320(7244):1240-1243.

doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240.

- Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA.

Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in

children and adolescents: International survey.

BMJ. 2007; 335(7612):194. doi:

10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55.

- Dkhar JW, Singh MS. Prevalence of Overweight

and Obesity among the Meitei Adolescent of

Manipur, India. The Anthropologist.

2012; 14(4): 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2012.11891256

- Rinya P. Food transition among tribal and

globalization with reference to Arunachal

Pradesh. J Soc Work Educ Prac. 2017;

2(1): 1-6. https://www.jswep.in/index.php/jswep/article/view/20

- Summan A, Nandi A, Schueller E, Laxminarayan

R. Public health facility quality and child

immunization outcomes in rural India: A

decomposition analysis. Vaccine.

2022;40(16):2388-2398. doi:

10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.017.

- Das P, Begum G. Nutritional Status of the Aka

Boys of Arunachal Pradesh. In Converging

Spectrum of Anthropology with Emphasis on Assam

and Adjoining Areas, edited by Bezbaruah, D, EBH

Publishers, India, Guwahati, 2020.

|