|

Introduction

Under 5

years children are generally considered as

nutritionally vulnerable segments of any Nation.

Malnutrition during childhood can also affect

growth potential and the risk of morbidity and

mortality in later years of life (1). In

developing countries like India, under nutrition

is one of the greatest problems among children.

According to the Global Hunger Index 2023 (2),

India ranks 111th out of the 125

countries. With a score of 28.7, India has

reported a serious level of hunger index. Chronic

under nutrition in childhood is linked to slower

cognitive development and serious health

impairments later in life that reduce the quality

of life of individuals (3). Undernourished

children are at higher risk of death from

infectious diseases due to poor immune response

and host defenses (4). It has been well

established that under nutrition in childhood is

the leading cause of high child mortality rates in

developing countries (5).

Anthropometry is a

widely accepted, low-cost technology for defining

the nutritional status of children (6). Recently,

the World Health Organization (WHO) developed age-

and sex-specific mid-upper arm circumference

(MUAC) cut-off points to determine child under

nutrition (7). In community-based studies,

mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) appears to be a

superior predictor of childhood under nutrition

than many other anthropometric indicators (6). The

mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) is an important

measurement that is often used for the assessment

among preschool children.

ICDS (Integrated

Child Development Services) scheme represents one

of the largest and most unique programs in the

Globe implemented for early childhood development

in India. The scheme was launched in the year 1975

(8). The package of services provided by the ICDS

scheme includes supplementary nutrition,

immunization, health check-ups, referral services,

nutrition and health education, and preschool

education (8). Children below six years are the

beneficiaries of this scheme.

However, few amounts

of literature exist regarding the prevalence of

under nutrition based on MUAC among preschool

children in West Bengal (9-13), in India (14-17)

and outside of India (4, 18-24). After an

extensive literature survey, it has been found

that, hitherto there is no work done by any

researcher having a similar kind of objectives.

So, this study aimed to evaluate the nutritional

status of children aged 2-5 years using mid-upper

arm circumference (MUAC) cut-off values. Following

the World Health Organization (7) age and

sex-specific cut-off points are used to assess the

nutritional status of ICDS children of Jalpaiguri,

West Bengal, India.

Material and Methods

A cross-sectional

study was carried out in randomly selected 44 ICDS

centers from January 2022 to October 2023 in

Maynaguri block, Jalpaiguri District, West Bengal,

India. Children aged 24 – 60 months (Boys - 499

and Girls - 522) from three (Rajbanshi, Nama

Shudra, Nashya Seikh) ethnicities were considered

for this study. Date of birth and ethnicity

identified by polio vaccination card provided by

ICDS workers.

The anthropometric

measurement of MUAC was measured by the author

(AB) on each subject following the standard

technique (25). The MUAC was measured using a

non-stretchable plastic measuring tape, to the

nearest 1 mm. The MUAC is the circumference of the

left upper arm, measured at the mid-point between

the tip of the shoulder and the tip of the elbow

(acromion and the olecranon process). Small marks

were made at the identified points. A tape was

placed over those two points, and the midpoint

between them was marked. Then the tape was placed

around the arm in such a manner that it was

touching the skin, but not compressing the soft

tissues

Normal children had

z-scores between -2SD and +2SD. Children with

z-score < -2SD were classified as

undernourished. Children having z-scores between –

3SD and -2SD were classified as moderately

undernourished and those having < -3SD as

severely undernourished.

Age and sex specific

mean and standard deviation of Mid upper arm

circumference was computed. Student’s t-test was

performed to test the sex difference in MUAC.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done to analyse

the significant age differences in the mean values

of MUAC. The Chi-square (χ2) test was also

performed to observe the significant difference in

the prevalence of under nutrition with various

factors. Statistical significance was set at

P<0.05. All types of statistical analysis were

done on SPSS V 18.

Results

|

Table 1: Age and sex-specific

distribution of Mean and standard

deviation of Mid Upper Arm Circumference

(MUAC).

|

|

Mid Upper Arm Circumference

|

|

Age (Months)

|

N (%)

|

Boys (cm)

|

N (%)

|

Girls (cm)

|

t-test

|

|

24-30

|

89 (17.84)

|

13.43 (1.03)

|

83 (15.90)

|

13.50 (1.21)

|

-.405

|

|

31-36

|

79 (15.83)

|

14.05 (1.23)

|

80 (15.33)

|

13.81 (1.31)

|

1.189

|

|

37-42

|

88 (17.63)

|

14.13 (0.85)

|

78 (14.94)

|

14.14 (1.24)

|

-.052

|

|

43-48

|

68 (13.63)

|

14.08 (0.97)

|

90 (17.24)

|

13.93 (1.21)

|

.882

|

|

49-54

|

83 (16.63)

|

14.73 (1.40)

|

94 (18.00)

|

14.33 (1.33)

|

1.918

|

|

55-60

|

92 (18.44)

|

14.83 (1.71)

|

97 (18.59)

|

14.64 (1.05)

|

.940

|

|

24-60

|

499 (100)

|

14.21 (1.33)

|

522 (100)

|

14.08 (1.27)

|

1.679

|

|

F value - 14.777***

|

F value - 9.465***

|

| P<0.001*** |

A total of 1021

children, 48.87 % boys and 51.13 % girls, aged

24-60 months old were measured in the present

study. Table 1 presents the percentage

distribution of the studied children, age and

sex-specific mean (SD) Mid-Upper Arm Circumference

(MUAC) of the sample. The mean MUAC of boys was

higher in every age group except for 24 - 30

months and 37 - 42 months. Age combined mean MUAC

value among boys was 14.21 (1.33) cm was greater

than girls 14.08 cm (1.27). Significant sex

difference in mean MUAC was not found at any age

group. One-way ANOVA reveals the mean MUAC

increased with age. Significant age differences

were found among both sexes for boys (F = 14.777;

p< 0.001) and girls (9.465; p< 0.001).

|

Table 2: Assessment of nutritional status

by using MUAC as a cut-off point

recommended by WHO (2007)

|

|

Age

(Months)

|

N

|

Boys

|

N

|

Girls

|

|

Moderate (-2SD) (%)

|

Severe (-3SD) (%)

|

Normal (%)

|

Moderate (-2SD) (%)

|

Severe (-3SD) (%)

|

Normal (%)

|

|

24-30

|

89

|

26 (30.23)

|

11 (12.79)

|

49 (56.98)

|

83

|

17 (20.48)

|

07 (8.43)

|

59 (71.08)

|

|

31-36

|

79

|

19 (24.05)

|

04 (5.06)

|

56 (70.89)

|

80

|

20 (25.00)

|

03 (3.75)

|

57 (71.25)

|

|

37-42

|

88

|

21 (23.86)

|

03 (3.40)

|

64 (72.74)

|

78

|

13 (16.67)

|

04 (5.13)

|

61 (78.20)

|

|

43-48

|

68

|

20 (29.41)

|

05 (7.35)

|

43 (63.24)

|

90

|

27 (30.00)

|

12 (13.33)

|

39 (56.67)

|

|

49-54

|

83

|

18 (21.68)

|

02 (2.41)

|

63 (75.91)

|

94

|

29 (30.85)

|

03 (3.19)

|

32 (65.96)

|

|

55-60

|

92

|

20 (21.73)

|

02 (2.17)

|

70 (76.10)

|

97

|

28 (28.86)

|

01 (1.03)

|

29 (70.10)

|

|

24-60

|

499

|

124 (24.85)

|

27 (5.41)

|

151 (69.74)

|

522

|

134 (25.67)

|

30 (5.75)

|

164 (68.58)

|

Table 2 describes the age and sex-specific

prevalence (%) of under nutrition based on MUAC

among the studied preschool children. The overall

percentage of moderate and severe undernourished

girls (moderate – 25.67 %; severe – 5.75 %) is

higher than the boys (moderate – 24.85 %; severe –

5.41%). The highest percentage of moderate under

nutrition was found in the age group 24-30 months

among boys (30.23 %) and 49-54 months among girls

(30.85 %). Whereas, the highest percentage of

severe under nutrition was found in the age group

24-30 months among boys (12.79 %) and 43-48 months

among girls (13.33 %).

|

Table 3: Age and Sex wise prevalence of

under nutrition among studied children

|

|

Undernourished (%)

|

Normal (%)

|

Total (%)

|

(χ2)

|

|

Age (Months)

|

|

24-30

|

61 (35.47)

|

111 (64.53)

|

172 (16.84)

|

13.345*

|

|

31-36

|

46 (28.94)

|

113 (71.06)

|

159 (15.57)

|

|

37-42

|

41 (24.70)

|

125 (75.30)

|

166 (16.26)

|

|

43-48

|

64 (40.51)

|

94 (59.49)

|

158 (15.48)

|

|

49-54

|

52 (29.38)

|

125 (70.62)

|

177 (17.34)

|

|

55-60

|

51 (26.98)

|

138 (70.02)

|

189 (18.51)

|

|

24-60

|

315 (30.85)

|

706 (69.15)

|

1021 (100)

|

|

Sex

|

|

Male

|

151 (30.26)

|

499 (69.74)

|

499 (48.87)

|

2.178NS

|

|

Female

|

164 (31.42)

|

358 (68.58)

|

522 (51.13)

|

|

*p<0.05, NS – Not Significant |

Table 3 shows the

sex-combined age-specific under nutrition based on

the MUAC cut-off value recommended by WHO 2007.

The highest percentage of under nutrition was

found in the age group 43-48 months (40.51 %) of

children and the lowest percentage of under

nutrition was found at 37-42 (24.70%) months of

children. Chi-square analysis (χ2-13.345) shows a

statistically significant relationship of under

nutrition with age groups. Results show that

female has a higher percentage of under nutrition

31.42 % than males 30.26 % but there is no

statistically significant relationship between

under nutrition with gender.

|

Table 4: Association of socio-economic

and socio-demographic factors with the

prevalence of MUAC-based under nutrition.

|

|

Factors

|

Sub-categories

|

N

|

Prevalence

|

(χ2)

|

|

Birth Weight

|

<2500 gm

|

297

|

126 (42.42)

|

26.291***

|

|

≥2500 gm

|

724

|

189 (26.10)

|

|

Ethnicity

|

Rajbanshi

|

349

|

95 (27.22)

|

19.815***

|

|

Namasudra

|

334

|

85 (25.45)

|

|

Nashyaseikh

|

338

|

135 (39.94)

|

|

Birth Order

|

1st

|

608

|

163 (26.80)

|

16.006***

|

|

2nd

|

358

|

125 (34.91)

|

|

3rd and above

|

55

|

27 (49.09)

|

|

Number of Siblings

|

0

|

461

|

115 (24.95)

|

18.165***

|

|

1

|

474

|

161 (33.97)

|

|

2

|

86

|

39 (45.35)

|

|

Bath Place

|

Open

|

401

|

151 (37.66)

|

14.329***

|

|

Closed

|

620

|

164 (26.45)

|

|

Fuel of Cooking

|

Wood

|

772

|

252 (32.64)

|

17.559***

|

|

Crop residue

|

15

|

10 (66.66)

|

|

LPG

|

234

|

53 (22.64)

|

|

Income level

|

<7501

|

289

|

118 (40.83)

|

18.911***

|

|

7501-15000

|

585

|

159 (27.18)

|

|

>15000

|

147

|

38 (25.85)

|

|

Asia specific Maternal BMI level

|

<18.5

|

110

|

40 (36.36)

|

28.728***

|

|

18.5-22.9

|

547

|

195 (35.65)

|

|

23-24.9

|

176

|

51 (28.98)

|

|

≥25

|

188

|

29 (15.43)

|

|

***p<0.001

|

Table 4 shows the

association between socio-economic and

socio-demographic variables prevalence of

mid-upper arm circumference-based under nutrition.

Birth weight below 2500 gm, children from

Nashyaseikh community, birth order 3rd

and above, number of siblings 2, open type of bath

place, crop residue as a fuel for cooking, monthly

income level Rs. <7501, maternal BMI level

<18.5 having the highest prevalence of

undernourished children. The χ2 analysis shows

that there were several factors such as birth

weight, ethnicity, birth order, number of

siblings, bath place, fuel of cooking, income

level and Asia-specific maternal BMI level were

statistically significant with the prevalence of

MUAC-based under nutrition.

Discussion

Childhood

malnutrition is an important health problem in

developing countries like India. The mean age of

children in our study was 42.48 (10.88) months for

boys and 43.14 (10.62) months for girls. In the

present study, the overall prevalence of under

nutrition was 30.85 %. The present study

documented that the overall prevalence of under

nutrition among girls (31.42 %) is higher than

that of boys (30.26 %), with few similar findings

reported by several scholars (11,17,24) and

contrary to the previous findings (4,10,13). The

percentage of moderate under nutrition is higher

than severe under nutrition among both genders.

The overall age and sex combined prevalence of

under nutrition was 30.85 % of which 25.27 % and

5.58 % of children were moderately and severely

undernourished, moderate under nutrition was found

higher than severe undernourished similar to the

previous studies (4,9,10,13,24).

In our study, we

found that the nutritional condition of ICDS

beneficiaries was serious with high rates of under

nutrition. The highest percentage of under

nutrition was found among Nashya Seikh children,

Rajbanshi children and Nama Shudra children

respectively. We suggest that more studies dealing

with under nutrition based on MUAC should be

undertaken among children of different

ethnicities. It was noticed that age, sex, and

ethnicity play a significant role in determining

the MUAC (4,9,10,13,24,26). Measurement of MUAC is

a quick and reliable method for screening children

to identify those who are seriously malnourished

(10,13). The application of MUAC appears to be a

better predictor for the assessment of childhood

under nutrition than many other anthropometric

indicators (11). The important finding of the

study is the significant association of age group

and ethnicity found with under nutrition in the

present study similar to a study previous study

(26).

|

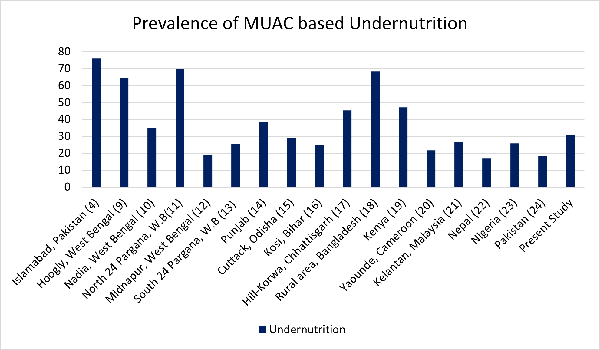

| Fig

1: Comparison of national and

international studies on the prevalence of

under nutrition based on MUAC |

Fig 1. Shows

comparison with international studies reveals that

the prevalence of under nutrition in the present

study is higher than the children of Cameroon

(21.60 %), Malaysia (26.80 %), Nepal (17 %),

Nigeria (25.70 %) and Pakistan (18.30 %). In the

context of India, the present study reported a

higher prevalence of under nutrition than the

children of Midnapur (18.96 %), South 24 Pargana

(25.61 %) of West Bengal, Odisha (29.10 %), Bihar

(25 %). Whereas higher prevalence was found than

the present study among children of Hooghly (64.50

%), Nadia (35.11 %) North 24 Pargana (69.80 %) of

West Bengal, Chhattisgarh (45.20 %), Punjab (38.52

%) in India. International studies from Kenya (47

%), Bangladesh (68.30 %) and Pakistan (76 %) show

a higher prevalence of under nutrition than the

present study.

Several

socio-economic and socio-demographic factors are

strongly associated with the prevalence of

MUAC-based under nutrition. Studies reported that

girls are more affected by under nutrition than

boys in rural areas(18,27). Birth Weight below

2500 grams has a significant relationship with

under nutrition(28-30). Different ethnic

backgrounds have an impact on child under

nutrition similar to the previous studies(31,32).

Few studies reported that birth order is highly

associated with under nutrition(18,27,33,34). A

higher number of siblings is also a reason behind

child under nutrition(35,36). There is a

significantly greater association of under

nutrition with children belonging to lower-income

groups (27,38,39). Maternal BMI level has an

impact on child under nutrition similar to

previous finding (37).

The present study

reveals that birth weight, ethnicity, birth order,

number of siblings, bath place, fuel of cooking,

income level and Asia-specific maternal BMI level

were important determinants of under nutrition

among children.

Conclusion

Assessment of

nutritional status by Mid Upper Arm Circumference

is a simple, reliable, easy-to-perform,

inexpensive, and conventional method for preschool

children. Furthermore, research on MUAC

representing communities with a larger sample size

is essential to monitor health status. Mid-upper

arm circumference-based under nutrition becomes

more effective for comparing the age and

sex-specific regional and ethnic differences of

children. Thus regular monitoring of health

scenarios among ICDS beneficiaries by MUAC may be

helpful to ameliorate the nutritional deficiencies

among preschool children. Therefore, the

Government should implement the policy of regular

surveillance in the form of nutritional surveys

and may also utilize the socio-economic and

socio-demographic variables as determining factors

of child malnutrition.

Acknowledgement

The researchers would like to thank

all the concerned ICDS workers and also the

parents of the subjects for their cooperation. We

thank those children who participated in this

research work. Special thanks to the CDPO of

Maynaguri for his support. However, the authors

assume full responsibility for all data and

content presented. Arindam Biswas recipient of a

Senior Research Fellowship (SRF-UGC-NET) by the

Government of India.

References

- Alderman H, Jesko H, Ricardo S. With the help

of one's neighbors: externalities in the

production of nutrition in Peru. Social

science and medicine. 2003;56:2019-2031.

- Global Hunger Index. India. Available at https://www.globalhungerindex.org/india.html

Accessed May 25th, 2024.

- Scrimshaw NS. Nutrition and health from womb

to tomb. Food and Nutrition Bulletin.

1997;18:1-21.

- Qayyum H, Mahwish R, Shagufta S, et al.

Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) as an

Assessment Tool, To Assess Nutritional Status in

Children Aged 6-60 Months in A Tertiary Care

Hospital, Islamabad. Age.

2021;12:1-92.

- Pelletier DL, The relationship between child

anthropometry and mortality in developing

countries: implications for policy, programs and

future research. The Journal of Nutrition

1994; 124: S2047-S2081.

- World Health Organization. World Health

Organization physical status: the use and

interpretation of anthropometry. World Health

Organization, Geneva. 1995.

- World Health Organization, Nutrition for

Health. WHO child growth standards: head

circumference-for-age, arm

circumference-for-age, triceps skinfold-for-age

and subscapular skinfold-for-age: methods and

development. WHO. 2007.

- Kapil U, Pradhan R. Integrated Child

Development Services scheme (ICDS) and its

impact on nutritional status of children in

India and recent initiatives. Indian

Journal of Public Health. 1999;43:21-25.

- Mandal GC, Bose K. Assessment of under

nutrition by mid-upper arm circumference among

preschool children of Arambag, Hooghly District,

West Bengal, India: An observational study. Internet

J Pediatr Neonatol 2009;11(1).

- Biswas S, Bose K, Mukhopadhyay A, et al.

Mid-upper arm circumference based under

nutrition among Bengalee children of Chapra,

West Bengal, India. Iranian Journal of

Pediatrics 2010; 20 (1):63.

- Bisai S. Nutrition status based on mid upper

arm circumference among urban, poor pre-school

children in north 24 Parganas, West Bengal,

India. Serbian Journal of Experimental and

Clinical Research. 2010; 11(4):141-145.

- Maiti S, De D, Ali KM et al. Evaluation of

Nutritional Status by Mid-Upper Arm

Circumference Amongst Affluent Children. Journal

of Nepal Paediatric Society 2012; 32(2).

- Giri SP, Biswas S, Bose K. Assessment of

Nutritional Status Using Mid-Upper Arm

Circumference among Bengalee Preschool Children

of Sagar Island, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal,

India. J Life Science. 2019;

11(1-2):1-6.

- Kaur G, Kang HS, Singal P, et al. Nutritional

status: anthropometric perspective of pre-school

children. The Anthropologist. 2005;

7(2):99-103.

- Mishra BK, Mishra S. Nutritional anthropometry

and preschool child feeding practices in working

mothers of central Orissa. Studies on Home

and Community Science. 2007;

1(2):139-144.

- Singh PK, Mukherjee B. Assessment of

nutritional status by mid upper arm

circumference (MUAC) among rural children of

Katihar district in Kosi region of Bihar. Journal

of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences.

2015; 4(22):3823-3829.

- Khan I, Parvin N. Nutritional assessment based

on mid upper arm circumference of the hill

Korwas under five year children in Sarguja

district, Chhattisgarh, India. International

Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences.

2018; 8(4):220-226.

- Roy NC. Use of mid-upper arm circumference for

evaluation of nutritional status of children and

for identification of high-risk groups for

malnutrition in rural Bangladesh. Journal

of Health, Population and Nutrition

2000:171-180.

- Barkley J, Newton C, Maitland K. Severe

malnutrition assessment in children in rural

Kenya. JAMA, 2005; 294:2577.

- Chiabi A, Tchokoteu PF, Takou V, et al.

Anthropometric measurements of children

attending a vaccination clinic in Yaounde,

Cameroon. African Health Sciences.

2008; 8(3):174-179.

- Whye Lian Cheah, Wan Muda WAM, Mohd Hussin ZA,

et al. Factors associated with under nutrition

among children in a rural district of Kelantan,

Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Public

Health. 24(2):330-342.

- Sharma KR. Malnutrition in children aged 6-59

months in Mugu district. J Nepal Health Res

Counc, 2012;10:156-159.

- Dairo MD, Fatokun ME, Kuti M. Reliability of

the Mid Upper Arm Circumference for the

Assessment of Wasting among Children Aged 12-59

Months in Urban Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J

Biomed Sci, 2012;8:140-3.

- Asif M, Aslam M, Altaf S. evaluation of

nutritional status of children using mid-upper

arm circumference (MUAC): A study from Pakistan.

Pak Pediatr J. 2017;41(3):163-7.

- Lohman TG. Anthropometric standardization

reference manual. Human kinetics books

1988:55-68.

- Das S, Banik SD, Bose K. Mid-upper arm

circumference for age and under nutrition among

2 to 6 year old Bauri and Santal children of

Purulia, West Bengal, India. Hum Bio Rev,

2013;2(4):359-372.

- Tigga PL, Sen J, Mondal N. Association of some

socio-economic and socio-demographic variables

with wasting among pre-school children of North

Bengal, India. Ethiopian Journal of Health

Sciences, 2015;25(1):63-72.

- Sayed NE, Mohamed AG, Nofal L. Malnutrition

among Pre-school Children in Alexandria, Egypt.

J Health Population Nutr.

2001;19(4):275-280.

- Paul VK, Sachdev HS, Mavalankar D, et al.

Reproductive health, and child health and

nutrition in India: meeting the challenge. Lancet.

2011;377(9762):332-349.

- Naregal PM, Durgawale PM, Kakade SV.

Association of socioeconomic factors with

nutritional status of 3–6-year-old preschool

children in urban slum areas of Karad. J

Datta Meghe Inst Med Sci Univ.

2023;18:1-7.

- Veghari G, Golalipour MJ. The Comparison of

Nutritional Status Between Turkman and

Non-Tutkman Ethnic Groups in North of IRAN. Journal

of Applied Sciences.

2007;7(18):2635-2640.

- Veghari G. The relationship of ethnicity,

socio-economic factors and malnutrition in

primary school children in north of Iran: a

cross-sectional study. Journal of Research

in Health Sciences 2013;13(1):58-62

- Som S, Pal M, Bhattacharya B, et al.

Socio-economic differentials in nutritional

status of children in the states of West Bengal

and Assam India. J Bisoco Sci. 2006;

38: 625-642

- Mondal N, Sen J. Prevalence of under nutrition

among children (5–12 years) belonging to three

communities residing in a similar habitat in

North Bengal, India. Ann Hum Biol.

2010;37:198–216.

- Biswas S, Bose K. Effect of Number of Rooms

and Sibs on Nutritional Status among Rural

Bengalee Preschool Children from Eastern India,

Coll. Anthropol. 2011;35(4): 1017–1022.

- Bisai S, Mahalanabis D, Sen A, et al. Maternal

Education, Reported Morbidity and Number of

Siblings are Associated with Malnutrition among

Lodha Preschool Children of Paschim Medinipur,

West Bengal, India. International Journal

of Pediatrics (Supplement 6),

2014;2(11):13-21.

- Chirande L, Charwe D, Mbwana H, et al.

Determinants of stunting and severe stunting

among under-fives in Tanzania evidence from the

2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC

Pediatrics. 2015;15:1-13.

doi:10.1186/s12885-015-0482-9.

- Kavosi E, Rostami ZH, Kavosi Z, et al.

Prevalence and determinants of under-nutrition

among children under six: a cross-sectional

survey in Fars province, Iran. Int J Health

Policy Manag. 2014;3(2):71–76.

- Tette EMA, Sifah EK, Nartey ET, et al.

Maternal profiles and social determinants of

malnutrition and the MDGs: What have we learnt?

BMC Public Health 2016;16(214):1-11.

doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2853-z.

|