|

Introduction

Enterococci

are one of the important cause of infections,

especially in the hospitalised patients. They are

normal commensals found in the intestines of the

humans. They are intrinsically resistant to

majority of the commonly used antibiotics in the

hospital like cephalosporins, aminoglycosides,

clindamycin etc. Therefore, these bacteria can

successfully cause nosocomial infections. (1)

There are various

known species of enterococci which can cause

infections in humans. E. faecium

infections are generally found to be more

difficult to treat compared to other species of

enterococci. In this study, we determined the

proportion of the enterococcal infections due to

the E. faecium species and the

differences in the epidemiology and susceptibility

profiles of the E. faecium isolates

compared to E. faecalis isolates in a

tertiary care hospital in Mangalore, in southern

India.

Methods

This prospective

cohort study was conducted at Father Muller

Medical College Hospital, Mangalore for a period

of six months from June to November 2023, after

ethical clearance from the Father Muller Institute

Ethics Committee (FMIEC/CCM /297 /2023).

Inclusion

criteria: Non repetitive clinical isolates

of Enterococcus species from various

clinical specimens like urine, exudates and blood

received in the microbiology laboratory.

Exclusion

criteria: The isolates of enterococci from

the stool and respiratory sample were excluded

from the study.

Procedure:

The samples were

cultured using 5% sheep blood agar (HiMedia

Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) and

MacConkey agar (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd.,

Mumbai, India Bac T/Alert aerobic culture bottle

(bio Mérieux, France) was used for blood culture.

All the suspected enterococcal isolates were

identified and speciated by standard biochemical

tests. The small translucent colonies on the 5%

sheep blood agar and corresponding pinpoint

magenta pink colonies were selected for colony

smear and Gram staining. The isolates were tested

for production of catalase enzyme. The

Gram-positive cocci in pairs, which did not

produce catalase enzyme, were further tested for

hydrolysis of bile esculin, fermentation of

mannitol, arabinose and motility. The isolates

which hydrolysed bile esculin were identified as Enterococcus

species. The non motile isolates were speciated as

E. faecalis or E. faecium

based on fermentation of arabinose. The

confirmation of identification of enterococci was

done by Bruker Daltonics Microflex LT/SH MALDI-MS

System (Bruker Daltonics, Germany).

Antibiotic

susceptibility testing was done by modified Kirby

Bauer disc diffusion method according to Clinical

Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines

(3). Antibiotic discs from HiMedia Laboratories

Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India were used. Enterococcus

faecalis ATCC strain 29212, Staphylococcus

aureus ATCC 25923 and Escherichia coli

ATCC 25922 were used as quality controls for

antibiotics. Ampicillin 10µg, high level

gentamicin 120 µg, nitrofurantoin 300 µg,

ciprofloxacin 5 µg, levofloxacin 5 µg, vancomycin

30 µg, teicoplanin 30 µg and linezolid 30 µg discs

were used for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Statistical

Analysis:

The statistical

analysis was done using SPSS version 23, IBM, USA.

The categorical variables have been expressed in

terms of percentages and frequencies. The

continuous variables are expressed as mean or

median based on the type of distribution. The chi

square test or Fishers exact test has been used as

test of significance between the categorical

variables. Independent t test or Man Whitney U

test were used for the analysis of continuous

variables.

Results

In the present

study, 132 isolates of the enterococci from the

urine, exudates and blood were included. The

median age of the patients with the enterococci in

clinical samples was 59 years.

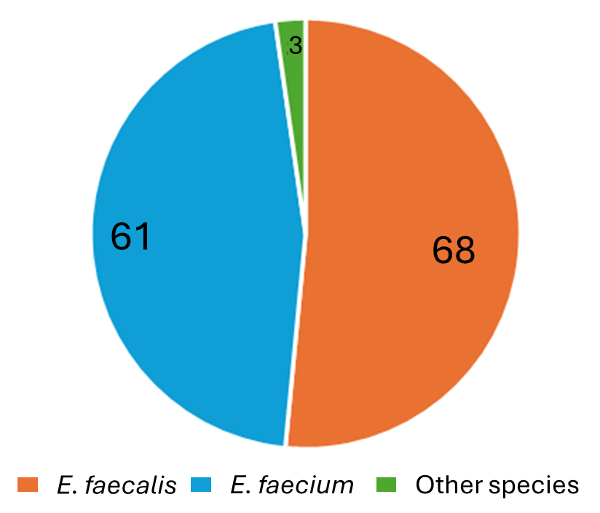

Among the isolates

included in the study, sixty-six (50%) each were

from males and females. On speciation, 68/132

(51.51%) isolates were identified as E.

faecalis, 61/132 (46.21%) as E.

faecium and2/132 (1.53%) isolates as E.

gallinarum and 1/132 (0.75%) as E.

raffinosus.

|

| Fig

1: Species distribution of the

enterococcal isolates |

|

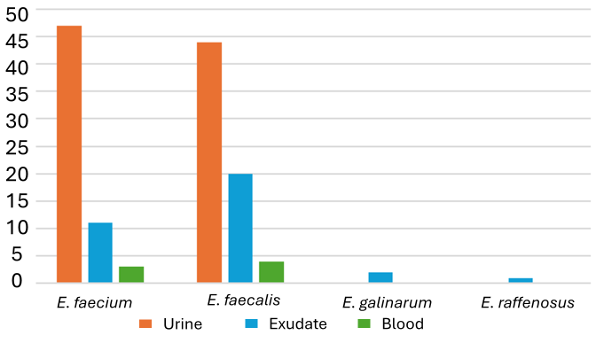

| Fig 2: Sample wise

distribution of the various enterococcal

species. |

Ninety-one (68.9%)

of the enterococcal isolates were from urine

samples, 34 (25.8%) of the isolates were from

exudates and 7 (5.3%) of the isolates were from

blood culture samples as shown in Fig 2.

Ninety-six (72.72%)

of the enterococcal isolates were from patients

admitted to the hospital, whereas 36 (27.27%) of

isolates were from the outpatient department. The

overall susceptibility testing of all the

enterococcal isolates is as in the Table 1. The

highest rate of resistance was against

fluoroquinolones, high level gentamicin,

ampicillin, nitrofurantoin, vancomycin and

teicoplanin. No resistance was detected in our

isolates against linezolid.

|

Table 1: Susceptibility of the

enterococcal isolates

|

|

Antibiotic Susceptibility Agents

|

Sensitive strains

|

Resistant strains

|

|

Number(n)

|

Percentage (%)

|

Number(n)

|

Percentage (%)

|

|

Ampicillin

|

86

|

65.15

|

46

|

34.85

|

|

High level Gentamicin

|

72

|

54.55

|

60

|

45.45

|

|

Ciprofloxacin

|

58

|

43.94

|

74

|

56.06

|

|

Levofloxacin

|

59

|

44.70

|

73

|

55.30

|

|

Nitrofurantoin

|

102

|

77.27

|

30

|

22.73

|

|

Vancomycin

|

124

|

93.93

|

10

|

7.58

|

|

Teicoplanin

|

126

|

95.45

|

06

|

4.55

|

|

Linezolid

|

132

|

100

|

00

|

00

|

The characteristics

of E. faecium compared with E.

faecalis are shown in Table 2. On

statistical analysis, it was found that E.

faecium was more significantly isolated

from the urine samples, whereas E. faecalis

was significantly more in the exudates. Also, E.

faecium was isolated significantly more in

the samples from the inpatient department. E.

faecium was found to be significantly more

resistant to ampicillin, high level gentamicin,

nitrofurantoin and vancomycin.

|

Table 2: Characteristics of the E.

faecium isolates

|

|

Enterococcus faecium

|

Enterococcus faecalis

|

P value

|

|

Median age

|

59

|

60

|

0.732*

|

|

Male

|

32 (52.5%)

|

33 (48.5%)

|

0.656†

|

|

Female

|

29 (47.5%)

|

35 (51.5%)

|

|

Urine isolates

|

47 (77%)

|

41 (60.3%)

|

0.041†

|

|

Exudate isolates

|

11 (18%)

|

23 (33.8%)

|

0.042†

|

|

Blood isolates

|

3 (4.9%)

|

4 (5.9%)

|

1.000‡

|

|

Isolates from inpatient departments

|

50 (82.0%)

|

43 (63.2%)

|

0.018†

|

|

Outpatient

|

11 (18.0%)

|

25 (36.8%)

|

|

Antibiotic Susceptibility

|

|

Ampicillin

|

Susceptible

|

26 (42.6%)

|

58 (85.3%)

|

0.000†

|

|

Resistant

|

35 (57.4%)

|

10 (14.7%)

|

|

High level Gentamicin

|

Susceptible

|

28 (45.9%)

|

43 (63.2%)

|

0.048†

|

|

Resistant

|

33 (54.1%)

|

25 (36.8%)

|

|

Ciprofloxacin

|

Susceptible

|

22 (36.1%)

|

36 (52.9%)

|

0.054†

|

|

Resistant

|

39 (63.9%)

|

32 (47.1%)

|

|

Levofloxacin

|

Susceptible

|

23 (37.7%)

|

36 (52.9%)

|

0.083†

|

|

Resistant

|

38 (62.3%)

|

32 (47.1%)

|

|

Nitrofurantoin

|

Susceptible

|

38 (62.3%)

|

62 (91.2%)

|

0.000†

|

|

Resistant

|

23 (37.7%)

|

6 (8.8%)

|

|

Vancomycin

|

Susceptible

|

54 (88.5%)

|

67 (98.5%)

|

0.026‡

|

|

Resistant

|

7 (11.5%)

|

1 (1.5%)

|

|

Teicoplanin

|

Susceptible

|

56 (91.8%)

|

67 (98.5%)

|

0.100‡

|

|

Resistant

|

5 (8.2%)

|

1 (1.5%)

|

|

Linezolid

|

Susceptible

|

61 (100%)

|

68 (100%)

|

-

|

|

Resistant

|

-

|

-

|

|

* - Mann Whitney U test; †- Chi square

test; ‡- Fishers exact test

|

Discussion

Enterococci are

important cause of infections in a wide range of

patients. They cause urinary tract infections,

blood stream infections and skin and soft tissue

infections. These infections tend to be resistant

to some of the common antibiotics used in the

hospitals. E. faecalis and E.

faecium are the 2 common species isolated

from the clinical samples.

The enterococcal

infections occurred in all the age groups of

patients in the hospital. The median age of the

patients with enterococcal isolates was 59 years.

This is in contrast to studies by Yadav and

Agarwal, and Mussadiq et al, where the maximum

number of isolates from age group 20-29 years and

21-40 years respectively. (4,5) The isolates were

equally distributed among males and females. In

contrast, Yadav and Agarwal observed that the

enterococci were isolated more among the female

patients. (4)

On speciation, 68

(51.51%) isolates were identified as Enterococcus

faecalis, 61 (46.21%) as Enterococcus

faecium and 2 (1.51%) isolates as Enterococcus

gallinarum and 1 (0.75%) as Enterococcus

raffinosus. Most of the studies in the

different places of India show a lower proportion

of E. faecium. The proportion of the E.

faecium in the different studies in New

Delhi, West Bengal, Sikkim have reported a

proportion of E. faecium varying between

8.5% to 28.8%. (6–11) Similar reports are also

available worldwide. (12,13) On the contrary,

Yadav and Agarwal, in a study conducted at Lucknow

reported higher proportion (47.5%) of E.

faecium. (4) Interestingly, two studies

from Mangalore show very different proportions of

E. faecium. (14,15) This shows there is

a varying proportion of E. faecium

infection in the country and the city, at

different time periods. The different studies have

reported few uncommon species of enterococci like

E. hirae, E. durans, E. avium, E. mundtii, E.

gallinarum etc. (6,7,9,10) This is similar

to our study where E. gallinarum and

E. raffinosus were detected. Hence it is

seen that majority of the enterococcal infections

in the country are caused by E. faecalis and

E. faecium.

Ninety-one (68.9%)

of the enterococcal isolates were from urine

samples, 34 (25.8%) of the isolates were from

exudates and 7 (5.3%) of the isolates were from

blood culture samples. This in contrast to the

various studies in India, where about 80% of the

isolates of enterococcal isolates were from the

urine samples. (4,6) A higher proportion of the

enterococci were reported from the exudate samples

in our facility.

Highest number of

the isolates in our study were resistant to

fluoroquinolones (55% and 56%). This is similar to

high resistance to fluoroquinolones, reported in

the various studies in the country. (4,7) Most of

the studies in the country report resistance of

enterococci to high level gentamicin of 30%- 55%.

(4,7,10,11,16) High level gentamicin resistance

was detected in 45.45% of the enterococcal

isolates in the present study. Ampicillin is a

good antibiotic to treat the enterococcal

infections, if found to be susceptible. Resistance

to ampicillin was detected in 34.85% of the

enterococcal isolates. Similar resistance rate to

ampicillin was documented by few studies, (6)

whereas other studies showed higher resistance

rates. (4,7) Nitrofurantoin is a very good drug

for susceptible enterococcal urinary tract

infections. Nitrofurantoin resistance was detected

in 22.73% of the isolates which is concordant with

other studies in the country. (6,7)

With the increased

use of vancomycin and teicoplanin in the hospital,

there has been development of enterococcal

vancomycin resistance. Vancomycin resistance was

observed in 7.58% of the isolates and teicoplanin

resistance in 4.55% of the isolates. This is in

contrast to a meta-analysis, where pooled

vancomycin resistance among the enterococcal

isolates from India was 12.4%. (17) There are

studies with various different rates of vancomycin

resistance in the country. (4,7–11) Chakraborty et

al, in a study in West Bengal in the year 2015,(9)

reported no vancomycin resistance, whereas Meena

et al, in a study published in 2017, reported a

high 37% of vancomycin resistant enterococci in

New Delhi. (8) The teicoplanin resistance in the

present study is lesser than in other similar

studies. (7,16)

There was no

linezolid resistance among all the enterococcal

isolates in the present study compared to a study

at New Delhi, where in a span of 3 years, 202

linezolid resistant enterococcal strains were

isolated. (18) Various studies in the country have

reported various rates of linezolid resistance.

(4,7,10)

The isolates of E.

faecium did not differ from other isolates

in terms of median age of the patients. The median

age of the patients in both the groups was 59

years. There was no significant difference in

terms of the gender of the patients. The E.

faecium, were more frequently isolated

from urine samples (77% vs 60.3 % p value = 0.041)

and less from the exudate samples (18% vs 33.8%, p

value = 0.042), when compared to E. faecalis.

There was no significant difference among the E.

faecium isolates in terms of the blood

sample (4.9% vs 5.9%, p value = 1.000). It was

observed in the study that E. faecium isolates

were isolated significantly more from the samples

of the inpatient departments when compared to E.

faecalis isolates (82% vs 63.2% p value =

0.018)

It was observed that

E. faecium isolates were significantly

more resistant to ampicillin (57.4% vs 14.7% p

value = 0.000). In their study at Etawah, Uttar

Pradesh, Musaddiq et al reported much higher

resistance to ampicillin in both E. fecium

and E. fecalis isolates (90.32% vs 84.78%)

(5). The E. faecium isolates were also

significantly more resistant to the high-level

gentamicin (54.1% vs 36.8% p value- 0.048),

nitrofurantoin (37.7% vs 8.8%, p value =0.000),

than E. faecalis isolates. E.

faecium isolates were found to be more

resistant, also to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin,

teicoplanin (8.2% vs 1.5%, p value = 0.100),

albeit not significantly when compared to the E.

faecalis isolates. Similarly, Das et al,

documented higher resistance rates of E.

faecium, compared to E. faecalis

isolates at New Delhi, (7) Similar higher

difference in resistance rates was observed in a

study in Tabriz, Iran. (12)

The E. faecium

isolates were significantly more resistant to

vancomycin than E. faecalis (11.5% vs

1.5%, p value = 0.026) which is concordant with

other studies. (4,7,12,16,19)

Limitations of the

study is that it is a single centre study and the

only the phenotypic characterisation of the

enterococcal isolates was done. This study

demonstrates a higher proportion of E.

faecium causing clinical infections than in

other parts of the country. E. faecium

in our study has significantly higher resistance

rates to ampicillin, high level gentamicin,

nitrofurantoin and vancomycin. Factors leading to

increased rates of E. faecium infections

and its antibiotic resistance need to be looked

for and addressed promptly.

Conclusion

In this study we

found that the proportion of the E. faecium

among the clinical isolates is higher compared to

many other studies. This is of concern, as the

resistance rates to various antibiotics are higher

among the E. faecium. The E.

faecium isolates were mostly from

inpatients indicating antibiotic overuse may be a

causal factor. There were significantly higher

rates of resistance seen among the E. faecium

isolates compared to E. faecalis

isolates in our study. Fortunately, the overall

rate of resistance to vancomycin is low and none

of the isolates were resistant to linezolid.

Strict infection control and antimicrobial

stewardship measures need to be taken in the

hospitals to decrease the prevalence of the E.

faecium infections and the resistance among

the enterococci to prevent any adverse outcome.

References

- Farsi S, Salama I, Escalante-Alderete E,

Cervantes J. Multidrug-Resistant Enterococcal

Infection in Surgical Patients, What Surgeons

Need to Know. Microorganisms.

2023;11(2):238..

- Procop GW. Koneman’s Color Atlas and Textbook

of Diagnostic Microbiology. Wolters Kluwer

Health; 2017.

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial

Susceptibility Testing. 33rd ed.

- Yadav R, Agarwal L. Enterococcal infections in

a tertiary care hospital, North India. Ann

Afr Med. 2022;21(3):193.

- Mussadiq S, Verma RK, Singh DP, et al.

Vancomycin Resistant Enterococcal Urinary Tract

Infection: A Potential Threat. Nat J Lab

Med. 2023;12(2):MO01-5.

- Mohanty S, Behera B. Antibiogram Pattern and

Virulence Trait Characterization of Enterococcus

Species Clinical Isolates in Eastern India: A

Recent Analysis. J Lab Physicians.

2022;14(03):237–46.

- Das A, Dudeja M, Kohli S, et al. Genotypic

characterization of vancomycin-resistant

Enterococcus causing urinary tract infection in

northern India. Indian J Med Res.

2022;155(3):423.

- Meena S, Mohapatra S, Sood S, et al.

Revisiting Nitrofurantoin for Vancomycin

Resistant Enterococci. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(6):DC19-22.

- Chakraborty A, Pal N, Sarkar S, et al.

Antibiotic resistance pattern of Enterococci

isolates from nosocomial infections in a

tertiary care hospital in Eastern India. J

Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6(2):394.

- Yadav G, Thakuria B, Madan M, et al. Linezolid

and Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci: A

Therapeutic Problem. J Clin Diagn Res.

2017;11(8):GC07-11.

- Sachan S, Rawat V, Umesh, et al.

Susceptibility pattern of enterococci at

tertiary care hospital. J Glob Infect Dis.

2017;9(2):73.

- Jahansepas A, Aghazadeh M, Rezaee MA, et al.

Occurrence of Enterococcus faecalis

and Enterococcus faecium in Various

Clinical Infections: Detection of Their Drug

Resistance and Virulence Determinants. Microb

Drug Resist. 2018 Jan;24(1):76–82.

- Álvarez-Artero E, Campo-Nuñez A, García-García

I, et al. Urinary tract infection caused by Enterococcus

spp.: Risk factors and mortality. An

observational study. Rev Clínica Esp Engl Ed.

2021;221(7):375–83.

- Bhat NR, Shivashankar SBK, Dhanashree B.

Antibiogram of Urinary Enterococcus Isolates

from a Tertiary Care Hospital. Infect Disord

- Drug Targets. 2021;21(1):146–50.

- Shridhar S, Dhanashree B. Antibiotic

Susceptibility Pattern and Biofilm Formation in

Clinical Isolates of Enterococcus spp.

Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2019

3;2019:1–6.

- Yangzom T, Kumar Singh TS. Study of vancomycin

and high-level aminoglycoside-resistant

Enterococcus species and evaluation of a rapid

spot test for enterococci from Central Referral

Hospital, Sikkim, India. J Lab Physicians.

2019 ;11(03):192–9.

- Smout E, Palanisamy N, Valappil SP. Prevalence

of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci in India

between 2000 and 2022: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect

Control. 2023 21;12(1):79.

- Rani V, Aye NK, Saksena R, et al. Risk factors

and outcome associated with the acquisition of

MDR linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium: a

report from tertiary care centre. Eur J Clin

Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin

Microbiol. 2024;43(4):767–75.

- Kilbas I, Ciftci IH. Antimicrobial resistance

of Enterococcus isolates in Turkey: A

meta-analysis of current studies. J Glob

Antimicrob Resist. 2018;12:26–30.

|