|

Introduction

As

males age, the prostate becomes one of the most

common organs to be affected, accounting for

significant mortality and morbidity. It can

present with a wide spectrum of lesions, such as

hyperplasia, atrophy, inflammation, metaplasia,

premalignant lesions, and malignancy. While a

pathologist must be well versed in the features of

malignancy, it is also essential to identify and

get familiarised with the various benign lesions

of the prostate, which are a handful. Most of them

coexist with each other.

The numerous benign

alterations can mimic carcinomas and premalignant

lesions. Thus, making the histopathological

diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma challenging.

Furthermore, both benign mimickers and

adenocarcinoma can occur in the same age group.

Therefore, it is important to prevent incorrect

interpretation since it could lead to serious

implications.

The lesions that are

most often misdiagnosed as cancer are atrophy and

its variants, including simple atrophy, partial

atrophy, and postatrophic hyperplasia due to their

high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, infiltrative

nature, and inconspicuous basal cell layer.[1]

Benign hyperplastic lesions are a group with

proliferating glands and no atypia.[1] Among

these, the architecture of adenosis is most

alarming since it is composed of small, crowded

glands with a fragmented basal cell layer.[1] A

variant of basal cell hyperplasia with prominent

nucleoli can also create confusion since it

presents small dark glands, variable nuclear

atypia, and prominent nucleoli.[1] Benign clear

cell cribriform hyperplasia can mimic Gleason

grade 4 prostatic adenocarcinoma, which also forms

glands in the cribriform arrangement.

Among the

metaplasia, florid mucinous metaplasia can mimic

the rare foamy variant prostatic adenocarcinoma,

where both show the presence of characteristic

abundant foamy cytoplasm and minimal cytologic

atypia. Nephrogenic metaplasia can mimic signet

ring cell carcinoma of Gleason grade 5 when the

tubules of metaplastic glands are lined by hobnail

cells with prominent nucleoli.[2] Sometimes, the

small lumens may also contain blue mucin,

mimicking Gleason grade 3 prostatic

adenocarcinomas.[2]

Clinically, in the

aging male population, benign enlargement of the

prostate gland compresses the urethra and causes

urinary obstruction with symptoms such as

increased urinary frequency, hesitation,

dribbling, and incomplete emptying of the

bladder[3], while carcinoma comes with its

challenges! The development of histologic features

of BPH is dependent on the bioavailability of

testosterone and its metabolite,

dihydrotestosterone.[4]

Globally, prostate

cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed

cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death

in men.[5] In a populated country like India, it

constitutes about 5% of all malignancies in

males.[6] The prevalence of BPH increases from 20%

at 40 years of age to about 90% by the eighth

decade of life![7] Prostate-specific antigen

(PSA), digital rectal examination, and transrectal

ultrasound are important tools for evaluation.[8]

However, biopsy remains the gold standard for

final diagnosis.[8]

Although we have a

limitation due to the lack of

immunohistochemistry, we took a keen interest in

conducting a study on the benign mimickers of

prostate adenocarcinoma relying solely on

morphology, the fundamental skill of a

pathologist. It has been challenging but fruitful

in improving our knowledge and observation skills.

We also did not come across many studies on the

web, that are focused entirely on the numerous

benign histopathological lesions. Hence, this

study is conducted considering the features of

various benign lesions, highlighting the mimickers

of carcinoma, and comparing their prevalences.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective

study was done in the Department of Pathology of

Veer Chandra Singh Garhwali Government Institute

of Medical Sciences for a period of two years,

i.e., from January 2022 to December 2023, after

approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

A total of 173 radical prostatectomy specimens

were received during this period.

The

histopathological data maintained in the

department of pathology were reviewed.

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections

were re-examined. New H&E-stained paraffin

sections were made whenever required, such as in

the case of faded slides, and re-staining and

re-mounting were done whenever required. All

relevant clinical details were reviewed from the

respective requisition forms submitted to the

Department of Pathology. The various prostate

lesions were listed, and the data was expressed

numerically and in percentages. Photomicrographs

of the benign lesions were taken.

Results

During the two-year

study period from January 2022 to December 2023,

the Department of Pathology received 173 radical

prostatectomy specimens. Of these, 156 were

diagnosed as benign lesions and 17 as malignant. A

variety of benign histopathological features were

observed and identified. They are listed in Table

1.

The most common

alteration found was Basal cell hyperplasia, which

was present in 66% of the cases, and the least

common was Nephrogenic metaplasia, which was found

in 3% of the cases.

|

Table 1: Histopathological features of

benign prostate lesions

|

|

Histopathological feature

|

No. of Cases

|

Percentage

|

|

1.

|

Acute inflammation

|

65

|

41.66

|

|

2.

|

Chronic inflammation

|

87

|

55.76

|

|

3.

|

Granulomatous inflammation

|

9

|

5.76

|

|

4.

|

Basal cell hyperplasia

|

104

|

66.66

|

|

5.

|

Clear cell cribriform hyperplasia

|

70

|

44.87

|

|

6.

|

Leiomyomatous hyperplasia

|

48

|

30.76

|

|

7.

|

Adenosis (atypical adenomatous

hyperplasia)

|

60

|

38.46

|

|

8.

|

Partial atrophy

|

52

|

33.33

|

|

9.

|

Simple atrophy

|

69

|

44.23

|

|

10.

|

Sclerotic atrophy

|

34

|

21.79

|

|

11.

|

Postatrophic hyperplasia

|

60

|

38.46

|

|

12.

|

Squamous metaplasia

|

51

|

32.69

|

|

13.

|

Mucinous metaplasia

|

34

|

21.79

|

|

14.

|

Transitional cell metaplasia

|

62

|

39.74

|

|

15.

|

Paneth cell-like change

|

25

|

16.02

|

|

16.

|

Nephrogenic metaplasia

|

5

|

3.20

|

|

17.

|

HGPIN

|

19

|

12.17

|

These histopathological features have been

broadly classified into five categories for

comparison. The categories are hyperplasia,

metaplasia, atrophy, inflammation, and

premalignant lesion, high grade prostatic

intraepithelial neoplasia, referred to as HGPIN.

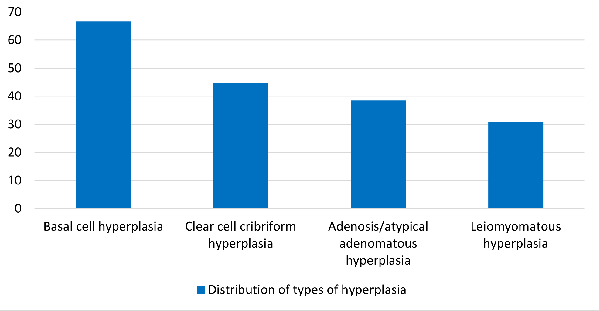

Among the hyperplastic lesions, the most common

was Basal cell hyperplasia constituting 66% of the

cases.

|

Graph

1: Hyperplastic lesions

|

The hyperplastic lesions are plotted in Graph 1.

We have found the three types of inflammation

mentioned in various literatures. They are acute,

chronic, and granulomatous. Among these, chronic

inflammation was the most common with a percentage

of 55%.

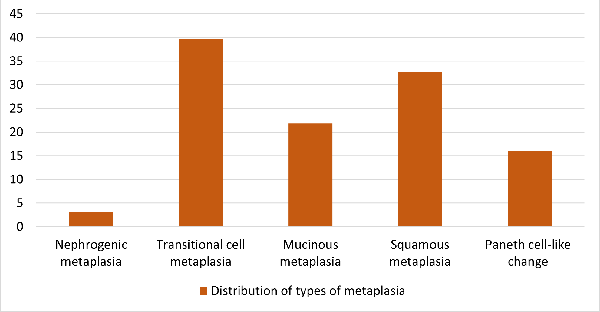

A variety of metaplastic lesions were observed in

our study. Out of these, transitional metaplasia

was the most common with a percentage of 39%.

These are shown in Graph 2.

|

| Graph

2: Metaplastic lesions |

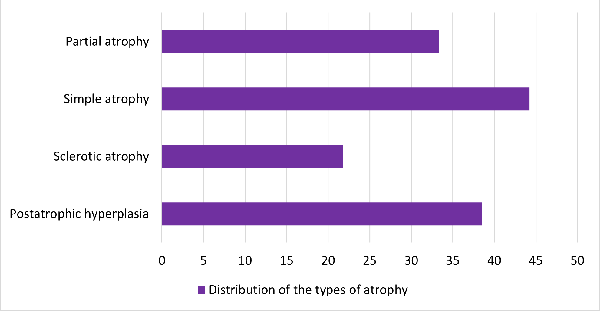

The various types of atrophy found are plotted in

Graph 3. Simple atrophy was the most common which

comprised 44% of cases.

|

| Graph

3: Atrophic lesions |

The only premalignant lesion found was High-Grade

Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (HGPIN), which

accounted for 12% of all benign cases. Although

some of the slides did show features favouring

Low-grade Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia

(LGPIN), it was not reported since LGPIN is highly

subjective, does not hold any pathologic

significance, and lacks clinical relevance.[9]

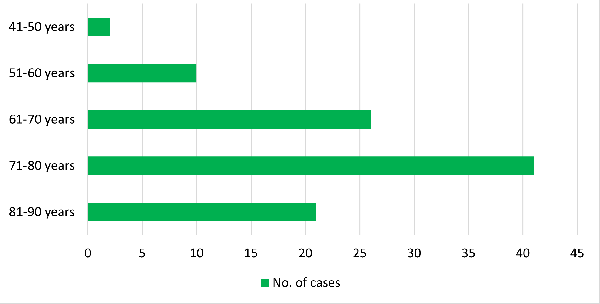

The age range in our study was 49 – 85, with the

maximum number of cases in the 7th decade of life.

The age-wise distribution of cases is shown in

Graph 4.

|

| Graph

4: Age-wise Distribution of Cases |

Discussion

Diseases of the

prostate are one of the most common causes of

decreased quality of life in the elderly male

population. They can cause urinary symptoms and,

in turn, discomfort to aging males. Being able to

distinguish benign mimics from prostatic

adenocarcinoma is of prime importance since an

incorrect diagnosis will cause trouble for the

patient and the doctor.

In our study, 156

prostate specimens were analysed that were

diagnosed as benign lesions. The age of the

patients ranged from 49 – 85 years, with the

maximum number of cases in the 7th

decade of life. Albasri et al. also found

a peak incidence of benign lesions in the age

range of 70-79.[10]

This supports the

fact that the frequency of prostatic lesions

increases as males grow older, with a high risk

for someone who has a family history of prostate

disease thereby revealing an underlying genetic

cause. In older males, testosterone starts to

decline, dihydrosterone increases, and oestrogen

remains the same. These hormonal changes bring

about an increase in growth factors, leading to

epithelial and stromal proliferation. Prostate

lesions are also associated with a lack of

physical activity, obesity, type 2 diabetes,

erectile dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease.

Most of these factors are common among the older

males.

Among

inflammation,chronic inflammation was found to be

the most common in our study. This concurs with

the study done by Pushpa et al., where

it comprised 40% of the cases.[11]

On microscopy,

lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates are present around

the glands and in the stroma. Lymphocytes may show

perinuclear clearing, appearing as signet ring

cells. This can mimic Gleason pattern 5 prostatic

adenocarcinoma which can exhibit signet ring cell

change.[12] Careful observation of the glandular

nuclear features is key. Chronic inflammation is

believed to be multifactorial. These include

previous infection of the genitourinary system,

instrumentation, immune system dysfunction,

psychological stress, and irregular hormone

activity, which are common in the aging male

population.

Acute inflammation

is associated with various nonneoplastic

epithelial alterations, such as atrophy,

hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, and transitional

metaplasia.[1,3] It is almost always associated

with benign lesions and rarely seen with

malignancy.[13]

Histologically, we

see sheets of neutrophils in and around the

glands, and in the stroma. Most cases of acute

inflammation are caused by bacteria responsible

for other urinary tract infections, including Escherichia

coli (80% of infections), other Enterobacteriaceae,

Pseudomonas, Serratia, Klebsiella,

and Enterococci.[14]

Granulomatous

inflammation occurs due to several reasons. They

can occur following procedures, due to infectious

agents, and systemic disease but mostly it is

nonspecific.[15] The nonspecific type is a

reaction to destroyed prostatic ducts/acini from

which bacterial toxins, cellular debris, and

glandular secretions spill into the stroma.[16]

Post-procedural granulomatous reaction is the

second most common cause of granulomatous

inflammation and may be seen following

transurethral resections or needle core

biopsies.[15] Infectious agents involved are

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG)-related therapy,

bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and viral

pathogens.[15] Systemic causes include

Sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss

syndrome, and allergic prostatitis.[17]

In the nonspecific

variant, there are dilated ducts and acini filled

with histiocytes, foamy macrophages, and rarely

multinucleated giant cells.[18] Stroma comprises

epithelioid histiocytes and occasional

multinucleated giant cells.[18] In the infectious,

postsurgical, and systemic variants, multiple

granulomas with or without necrosis are seen,

along with histiocytes and giant cells.[18] It is

quite common to find a mixed inflammatory

infiltrate comprising neutrophils and lymphocytes

in all the variants. Eosinophils are found in

allergic prostatitis.[18]

In prostatic

adenocarcinoma post-therapy, tumor cells are

single with foamy cytoplasm and less nucleolar

prominence.[19] This mimics lipid-laden

epithelioid macrophages. Identifying the residual

glands in such cases is important, too.[19]

Diffuse granulomatous inflammation may mimic

high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma.[19] Taking

note of nucleolar prominence in carcinoma is

important.

Basal cell

hyperplasia (BCH)was the most common hyperplastic

lesion found in our study, which is similar to the

study done by Mahapatra et al.[20] The

presence of nodular proliferation of glands with

multiple layers of basal cells having scant

cytoplasm gives the glands a basophilic

appearance. Intraluminal eosinophilic amorphous

secretions and cribriform architecture may be

seen. Nuclei are crowded with pinpoint nucleoli.

At higher magnification, basal cells are seen

oriented both parallel and perpendicular to the

basement membrane.[21]

Florid BCH, BCH with

prominent nucleoli, and BCH with cribriform

pattern must be distinguished from adenocarcinoma.

BCH is basophilic due to the multilayering of

basal cells and scant cytoplasm. It can present as

solid nests and lack nuclear pleomorphism.

Adenocarcinoma has an irregular arrangement of

cells, with relatively more abundant cytoplasm,

giving an eosinophilic or amphophilic appearance.

It exhibits pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli.

BCH, with prominent nucleoli, mimics HGPIN as

well. Its cells are perpendicular and parallel to

the basement membrane, with frequent solid nests

and uniform nuclei. On the contrary, HGPIN shows

crowding of large pleomorphic nuclei. BCH occurs

either due to a primary response to the luminal

epithelial apoptosis or a secondary response to

inflammation.[22] It also occurs following

androgen deprivation therapy and radiation

therapy.[23]

Adenosis, formerly

called atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, comprises

a nodular, well-circumscribed proliferation of

small, crowded glands with pale, abundant

cytoplasm without prominent nucleoli. The

flattened basal cell layer is partially intact and

fragmented, which may be difficult to visualize.

Adenosis mimics

low-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma, which also

comprises small, crowded glands. Carcinoma has

enlarged pleomorphic nuclei with prominent

nucleoli. It also has straight luminal borders and

a more infiltrative growth pattern. It lacks

larger, classic-appearing nonneoplastic glands

that are often intermixed with benign

adenosis.[24]

In clear cell

cribriform hyperplasia, hyperplastic prostatic

glands show cribriform architecture and contain

pale cytoplasm. Lumens are of varying sizes. The

basal cell layer is intact and prominent. Nuclei

are small and uniform with pinpoint nucleoli.

Prostatic adenocarcinoma Gleason pattern 4 variant

also appears to have a cribriform pattern but with

enlarged pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli,

and absence of basal cells.[25 ]

Leiomyomatous

hyperplasia is when there is increased

proliferation of stromal cells with minimal

glandular proliferation. The glands are compressed

by the increasing stroma. Bland fibromuscular

spindle cells, small blood vessels, and a myxoid

or hyalinised stroma form stromal nodules.

The morphological

differences between clear cell cribriform

hyperplasia, adenosis, and prostatic

adenocarcinoma have been enumerated in Table 2.

|

Table 2: Morphological differences

between clear cell cribriform hyperplasia,

adenosis, and carcinoma.

|

|

Characteristics

|

Clear Cell Cribriform Hyperplasia

|

Adenosis

|

Carcinoma

|

|

Architecture

|

Large normal-sized glands with cribriform

pattern.

|

Well-circumscribed, lobular, small

crowded glands.

|

Diffused, disordered, and infiltrative

glands. (Gleason grade 4 form cribriform

pattern; Gleason grade 3 form well-formed

glands with lumen)

|

|

Cytoplasm

|

Clear cytoplasm.

|

Abundant, pale eosinophilic to clear.

|

Mostly amphophilic, can be eosinophilic.

|

|

Nucleus

|

Small, uniform, round.

|

Small, uniform, round.

|

Large, pleomorphic crowding.

|

|

Nucleoli

|

Inconspicuous to Pinpoint.

|

Inconspicuous to Pinpoint.

|

Enlarged, prominent.

|

|

Basal cell layer

|

Prominent, continuous.

|

Fragmented, patchy.

|

Absent.

|

|

Inflammation

|

Common.

|

Common.

|

Rare.

|

|

Corpora Amylacea

|

Common.

|

Common.

|

Rare.

|

|

Blue tinged mucin

|

Rare.

|

Rare.

|

Common.

|

According to an

article by Bostwick et al., the

incidence of isolated HGPIN averages 9% (range

4%-16%) of prostate biopsies in the United States

every year.[26] In our study, HGPIN comprised 12%

of the cases during the 2-year time frame.

High-grade prostatic

intraepithelial neoplasia,orHGPIN, is a

premalignant lesion with cytological and

architectural atypia. Epithelial cells

proliferate, comprising nuclear and nucleolar

abnormalities.

On microscopy, four

architectural patterns can be seen. They are

tufting, micropapillary, cribriform, and flat.

Under low power, the glands appear darker and more

basophilic than normal. Layers of crowded,

pseudostratified secretory cells show enlarged and

irregular nuclei, hyperchromasia, and prominent

nucleoli at 20× magnification.[27] Chromatin is

coarse and clumpy.[27]

HGPIN is more common

in the peripheral zone of the prostate and is

often located adjacent to the foci of cancer.[27]

The presence of a basal cell layer differentiates

it from adenocarcinoma. Transitional cell

metaplasia has nuclear grooves which helps to

distinguish it from HGPIN.

HGPIN is more common

in men with prostate cancer.[27] Men with HGPIN on

initial core biopsy have a higher risk of prostate

carcinoma in the subsequent biopsy as compared to

those without HGPIN.[27] Carcinoma is most likely

to develop within 10 years of HGPIN.[26] HGPIN and

adenocarcinoma share the same causative factors,

including excess dietary fat, androgens, chronic

inflammation, and genetic mutations.[28] Loss of

p27 in HGPIN ultimately causes localized prostatic

adenocarcinoma.[28] Figure 1 shows the

morphological features of basal cell hyperplasia,

clear cell cribriform hyperplasia, adenosis, and

HGPIN.

|

| Figure

1: (a) Photomicrograph showing

basal cell hyperplasia of prostate glands

(40x, H&E). Inset shows a prostate

gland with multilayered basal cells (400x,

H&E). (b) Photomicrograph of prostate

glands showing cribriform architecture

(100x, H&E). Inset shows a gland with

clear cells arranged in cribriform pattern

(400x, H&E). (c) Photomicrograph of

adenosis showing small crowded glands

(100x, H&E). (d) Photomicrograph of

HGPIN with flat architecture (100x,

H&E). Inset shows tufted HGPIN with

pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli

(400x, H&E). |

Although not many

studies have encountered a wide range of

metaplasia, Abdollahi et al. conducted a

study where transitional cell metaplasia showed

the highest incidence, similar to ours.[29]

In transitional cell

metaplasia, transitional (urothelial) cells line

prostatic ducts or glands.[30] Glands may show a

spectrum of changes like that in the bladder,

including von Brunn’s nests and cystitis cystica

with punched-out lumens.[30] Lumens often contain

corpora amylacea. The glands have a multilayered

epithelial lining that imparts a basophilic

appearance. The cytoplasm is minimal and pale.[30]

Perinuclear clearing and longitudinal nuclear

grooves are present.[30]

Transitional cell

metaplasia can mimic high-grade prostatic

intraepithelial neoplasia. In contrast to

transitional cell metaplasia, HGPIN comprises

cytological atypia with prominent nucleoli and

lacks nuclear grooves. HGPIN also shows an array

of architectural patterns that are not present in

metaplasia.

It is induced by

tissue damage and associated with inflammation,

infarction, and post-therapy.[30] It is often

associated with a previous local irritation or

trauma due to surgical resections,

instrumentation, or stones.[2] In some cases, it

may occur after renal transplantation.[2] Such

situations are most prevalent in aging males.

Squamous metaplasia

is when squamous cells line prostate glands or

ducts.[30] It is also induced by tissue damage and

related to inflammation, infarction, radiation

therapy, and androgen deprivation therapy.[30 ]It

shows the presence of intercellular bridges, dense

eosinophilic cytoplasm, and inflammatory cell

infiltrate.

It should be kept in

mind that squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate

is a rare entity.[31] In carcinoma, the nucleus

shows marked atypia, hyperchromasia, and abnormal

mitotic figures. These nuclear features are not

found in metaplasia. Carcinoma is also not

associated with areas of infarction or

inflammation.[31]

In Mucinous

metaplasia, the prostate glands have mucin-filled

apical cells. The acinar cells are columnar,

containing abundant clear to blue cytoplasm.

Nuclei are pyknotic, small, and round, but mostly

it is flattened. As the acinar cell nuclei are

pushed by mucin towards the basal surface, basal

cells may be difficult to visualize without

immunohistochemistry.[32]

The extravasation of

mucin into the lumens may raise concern, as this

is a feature of adenocarcinoma. One must look for

the presence of basal cells, whether or not there

is an infiltrative growth pattern, and the

presence of more classic benign appearing prostate

glands to differentiate it from foamy-variant

prostatic adenocarcinoma. Although this variant of

prostatic adenocarcinoma is rare, it shows minimal

to no cytological atypia and pink luminal

secretions. It also comprises small hyperchromatic

nuclei which may make it difficult to visualise

the nucleoli. In such cases, special stains may be

required. The foamy variant of adenocarcinoma is

positive for colloidal iron, alcian blue, and

P504S[33] whereas mucinous metaplasia is positive

for mucicarmine and PAS.

In Nephrogenic

metaplasia, small glands show renal tubular

expression close to the urothelium. It is

associated with prior urothelial trauma due to

instrumentation, urethral catheterization,

infection, or calculi. It also occurs after renal

transplantation.

It is associated

with acute and chronic inflammation. Lesions are

composed of small tubules showing a variety of

histologic appearances. They may be small or

dilated and lined by a single layer of epithelial

cells that are cuboidal or flattened. Cells may

also show a hobnail or signet ring appearance.

When it involves the surface, it gives a papillary

appearance. The cells contain eosinophilic to

clear cytoplasm. The tubules may contain dense

eosinophilic material, resembling the thyroid.

Nephrogenic metaplasia can mimic prostate acinar

adenocarcinoma. A thickened eosinophilic hyaline

rim may form around the tubules, which helps

differentiate it from carcinoma. Carcinoma also

has prominent cellular atypia with a diffused and

disordered growth pattern. The cells are

amphophilic and pleomorphic, with large and

prominent nucleoli. Inflammation is rare.

Paneth cell-like

change can be seen in both benign and malignant

lesions. The presence of collections of prostatic

cells with eosinophilic granules in the cytoplasm

resembles intestinal Paneth cells.[34] Represents

either (a) PAS-positive, diastase-resistant

eosinophilic cytoplasmic granular change in the

benign prostatic epithelium or (b) endocrine

differentiation with neuroendocrine granules in

the dysplastic and malignant prostatic

epithelium.[35] There is no cytological atypia. It

is also called eosinophilic metaplasia.

It is a reactive

change of the prostatic epithelium to radiation

therapy, granulomatous prostatitis, and hormone

therapy. It is almost always associated with

inflammation. It can mimic prostatic

adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell differentiation.

Glands in adenocarcinoma are infiltrative and

angulated, often with collapsed lumina. However,

they tend to be of low grade and low stage.[36]

Paneth cell metaplasia has round, uniform, and

circumscribed groups of glands without atypia. Figure

2 shows the morphology of squamous

metaplasia, mucinous metaplasia, transitional cell

metaplasia, and paneth cell-like change.

|

| Figure

2: (a) Photomicrograph of

squamous metaplasia of prostate glands.

(100x, H&E). (b) Photomicrograph showing

mucinous metaplasia of prostate glands.

(400x, H&E). (c) Photomicrograph of

transitional cell metaplasia of prostate

glands showing multilayered epithelial

lining comprising cells with nuclear

grooves. (400x, H&E). (d)

Photomicrograph of Paneth cell-like change

showing eosinophilic granules in the

cytoplasm of glandular epithelial cells.

(400x, H&E). |

There are four types

of atrophy found in our study. They are simple,

partial, sclerotic, and postatrophic hyperplasia

(hyperplastic). Out of these, the most common

atrophy was simple atrophy, which is similar to

the study done by Postma et al., where

the incidence of simple atrophy was 91%.[37]

Atrophy is when

there is a decreased volume of cytoplasm in

prostatic acinar luminal cells. The decrease in

cytoplasm leads to an increased

nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. This alteration is a

response to injury caused by chronic ischemia.[38]

Ischemia can be due to locoregional

arteriosclerosis which is common in the older male

population. Atrophy is also caused by radiation

treatment or androgen ablation.[38]

Simple atrophy is

when the decrease in cytoplasm is severe, making

the glandular epithelial cells appear flattened

and basophilic. The glands appear dilated. The

cell membrane lies just adjacent to the nucleus,

yielding a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and

is often associated with inflammation. Cystic

glandular dilation may also occur. In the article

by Trpkov et al., it is mentioned that

simple atrophy is the most common morphologic

variant, and the term ‘atrophy’ is typically used

to designate simple atrophy.[2] It is typically

associated with inflammation.[2] Chronic

inflammatory infiltrates are often found within

and around the foci of atrophy.[2] On the

contrary, inflammation is rarely seen in the foci

of prostatic adenocarcinoma.[2] Simple atrophy

occurs following treatment with antiandrogens and

radiation.[2]

Partial atrophy

occurs when the decrease in cytoplasm is moderate,

with cells having some pale eosinophilic

cytoplasm. The glands may have an infiltrative

appearance. Various luminal shapes can be seen.

They are infoldings, undulations, and straight

luminal borders. Since basal cells are difficult

to identify and due to prominent acinar

architectural distortion, partial atrophy can be

misinterpreted as low-grade prostatic

adenocarcinoma. This variant of atrophy is the

most problematic since it can appear disorganized

and infiltrative with irregular growth.[39] It

also lacks the basophilic appearance that is

typically seen in simple atrophy and postatrophic

hyperplasia.[39] Acinar adenocarcinoma has

prominent atypia in addition to diffused and

disordered growth.[39] Cells have amphophilic

cytoplasm and nuclear crowding. Nuclei are large

and atypical, comprising large prominent

nucleoli.[39] In carcinoma, blue-tinged mucin is

commonly seen, while corpora amylacea is rare.[39]

In Sclerotic

atrophy, there is marked sclerosis around the

acini. This makes the glands appear angular,

distorted, and infiltrative. Postatrophic

hyperplasia (hyperplastic atrophy) has a central

dilated duct with smaller atrophic acini around it

in a lobular configuration.[40] Stroma appears

sclerotic.

Prostatic

adenocarcinoma (atrophic type) can mimic simple

and sclerotic atrophy.[40] Atrophic adenocarcinoma

is often intermixed with non-atrophic conventional

prostate carcinoma and has less basophilic

cytoplasm and cytological atypia. Figure 3

shows the morphology of nephrogenic metaplasia,

partial atrophy, sclerotic atrophy, and

postatrophic hyperplasia.

|

| Figure

3: (a) Photomicrograph of

nephrogenic metaplasia where prostate

glands display a single cell lining with

fine chromatin and hobnailing (arrows)

(400x, H&E). (b) Photomicrograph of

partial atrophy in which many prostatic

acini are infiltrative and display

infoldings and angulated luminal contours

(100x, H&E). (c) Photomicrograph of

sclerotic atrophy showing marked sclerosis

surrounding prostatic acini (100x,

H&E). (d) Photomicrograph of

postatrophic hyperplasia showing a central

atrophic dilated duct with surrounding

smaller atrophic acini. (400x, H&E).

|

Conclusion

With a wide array of

benign lesions and mimics, it is important to be

aware of and get familiarised with the

characteristic morphological features of each

lesion, to identify them correctly and prevent any

false positive interpretation. In addition, proper

handling and processing of the tissue specimens

must be ensured. Special stains and immunostains

must be used whenever required.

References

- Egevad L, Delahunt B, Furusato B, Tsuzuki T,

Yaxley J, Samaratunga H. Benign mimics of

prostate cancer. Pathology. 2021

Jan;53(1):26-35

- Trpkov K. Benign mimics of prostatic

adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2018;31

(Suppl 1):22–46.

- McNeal JE. Origin and evolution of benign

prostatic enlargement. Invest Urol. 1978;15(4):340–345

- Nwafor CC, Keshinro OS, Abudu EK. A

histopathological study of prostate lesions in

Lagos, Nigeria: A private practice experience. Niger

Med J 2015;56:338-43

- Dabir PD, Ottosen P, Hoyer S, Hamilton-Dutoit

S. Comparative analysis of three- and

two-antibody cocktails to AMACR and basal cell

markers for the immunohistochemical diagnosis of

prostate carcinoma. Diagn Pathol.

2012;7:81

- ICMR. Consolidated report of population based

cancer registries 2001-2004: incidence and

distribution of cancer. Bangalore (IND):

Coordinating Unit, National Cancer Registry

Programme, Indian Council of Medical Research;

2006

- Lakhtakia R, Bharadwaj R, Kumar VK, Mandal P,

Nema SK. Immunophenotypic characterization of

benign and malignant prostatic lesions. Med

J Armed Force India. 2007;63:243-8

- Garg M, Kaur G, Malhotra V, Garg R.

Histopathological spectrum of 364 prostatic

specimens including immunohistochemistry with

special reference to grey zone lesions. Prostate

Int. 2013;1(4):146-151

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 2:68

- Albasri A, El-Siddig A, Hussainy A, Mahrous M,

Alhosaini AA, Alhujaily A. Histopathologic

characterization of prostate diseases in

Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 2014;15(10):4175-9

- Pushpa N, Goyal R, Bhamu S. Histopathological

Spectrum of Prostatic Lesions and Their

Correlation with Serum Prostate Specific Antigen

Levels. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and

Clinical Research. Feb. 2024;17(2):36-39.

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:5

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:4

- MacLennan GT, Resnik MI, Bostwick DG.

Pathology for Urologists. Pennsylvania.

Saunders; 2003; 3:84

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:8

- Warrick J, Humphrey PA. Nonspecific

granulomatous prostatitis. J Urol. 2012

Jun;187(6):2209-10

- Furusato B, Koff S, McLeod DG, Sesterhenn IA.

Sarcoidosis of the prostate. J Clin Pathol.

2007 Mar;60(3):325-6

- Epstein JI, Hutchins GM. Granulomatous

prostatitis: distinction among allergic,

nonspecific, and post-transurethral resection

lesions. Hum Pathol. 1984

Sep;15(9):818-25.

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:10

- Mahapatra QS, Mohanty P, Nanda A, Mohanty L.

Histomorphological study of prostatic

adenocarcinoma and its mimics. Indian J

Pathol Microbiol. 2019

Apr-Jun;62(2):251-260

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:32

- Thorson P, Swanson PE, Vollmer RT, Humphrey

PA. Basal cell hyperplasia in the peripheral

zone of the prostate. Mod Pathol. 2003

Jun;16(6):598-606

- Kruithof-Dekker IG, Têtu B, Janssen PJ, Van

der Kwast TH. Elevated estrogen receptor

expression in human prostatic stromal cells by

androgen ablation therapy. J Urol. 1996

Sep;156(3):1194-7

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:26

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:36

- Bostwick DG, Qian J. High-grade prostatic

intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol.

2004 Mar;17(3):360-79

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 2:68

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins Basic

Pathology. 10th ed. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC,

editors. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier - Health

Sciences Division; 2021

- Abdollahi A, Ayati M. Frequency and outcome of

metaplasia in needle biopsies of prostate and

its relation with clinical findings. Urol J.

2009 Spring;6(2):109-13

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:38

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:40

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:41

- Zhou M, Jiang Z, Epstein JI. Expression and

diagnostic utility of

alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase (P504S) in foamy

gland and pseudohyperplastic prostate cancer. Am

J Surg Pathol. 2003 Jun;27(6):772-8

- Weaver MG, Abdul-Karim FW, Srigley JR. Paneth

cell-like change and small cell carcinoma of the

prostate. Two divergent forms of prostatic

neuroendocrine differentiation. Am J Surg

Pathol. 1992 Oct;16(10):1013-6

- Weaver MG, Abdul-Karim FW, Srigley J, Bostwick

DG, Ro JY, Ayala AG. Paneth cell-like change of

the prostate gland. A histological,

immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic

study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992

Jan;16(1):62-8

- Salles DC, Mata DA, Epstein JI. Significance

of Paneth cell-like differentiation in prostatic

adenocarcinoma: a retrospective cohort study of

80 cases. Hum Pathol. 2020 Aug;102:7-12

- Postma R, Schröder FH, van der Kwast TH.

Atrophy in prostate needle biopsy cores and its

relationship to prostate cancer incidence in

screened men. Urology. 2005

Apr;65(4):745-9

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:12

- Xu Y, Wang Y, Zhou R, Li H, Cheng H, Wang Z,

Zhang J. The benign mimickers of prostatic

acinar adenocarcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016

Feb;28(1):72-9

- Zynger DL, Parwani AV, Suster S. Prostate

Pathology. New York. Demos Medical; 2015; 1:22

|