|

Introduction

A

diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is defined as a

protrusion of abdominal viscera into the thoracic

cavity through a defect within the diaphragm. Most

commonly the disorder is congenital in nature,

arising due to the failure of complete

diaphragmatic fusion during embryologic

development. The less common acquired variant is

secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma to the

abdomen / thorax or iatrogenic causes [1, 2], and

generally termed as posttraumatic diaphragmatic

hernias (PTDHs). The presentation may be acute

with haemodynamic and respiratory instability or

else, they may go undiagnosed at the initial

trauma at all and manifest months or years later

as a diaphragmatic hernia [3]. They can present a

diagnostic and therapeutic challenge and have an

overall mortality rate of up to 31% [4].

In this retrospective analysis, we describe our

experience with patients who reported to the

general surgical unit of a medical college in the

Kashmir Valley with delayed presentations of PTDH.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective

study was conducted at the Department of Surgery,

SKIMS Medical College, Srinagar, Kashmir, India.

The medical records of all the patients treated

for delayed presentation of PTDH from June 2010 to

May 2024 were retrieved from the databank.

Carter’s

classification criteria [5] concern the temporal

parameter of the development of PTDH and recognize

three phases: the acute phase (up to 14 days after

injury), the interval or latent phase when

patients may be asymptomatic, and the obstructive

phase when symptoms start appearing. The latter

two phases are collectively referred to as delayed

PTDH, and in this study, presentation in these

phases was the single inclusion criterion to be

fulfilled. The exclusion criteria included acute

PTDH and congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

This study did not

involve any invasive interventions but relied on a

retrospective analysis of stored data and was

approved by the departmental review committee.

Proper informed consent was sought from the

patients for publication the data and the

accompanying images, after assuring them of

privacy and confidentiality, under the Declaration

of Helsinki.

Results

The patient characteristics are depicted in Table

1 .

|

Table 1: Patient characteristics

of posttraumatic diaphragmatic hernia

|

|

Serial number

|

Gender

|

Age (y-year)

|

History (d- day, w -week,

m-month, y-year)

|

Type of index injury

|

Treatment of index injury

|

Interval since index injury (m-

month; y – year)

|

Site of hernia

|

Imaging

|

Surgical approach

|

Operation findings

|

Management

|

Postoperative phase &

follow-up

|

|

1

|

F

|

50

|

AP, Vom - 1 d

O/E

Decreased

BS at base of left lung

|

B (fall from height)

|

Co

|

5m

|

L

|

CXR: Elevated (L) hemidiaphragm

CECT: DH with collapse of ipsilateral

lung and mild pleural effusion

|

Lap

|

Herniated omentum and SI; diaphragm

defect 7 x 5 cm

|

Reduction of DH, mesh repair of

diaphragm, chest tube

|

Uneventful, no recurrence at 1 y

|

|

2

|

F

|

17

|

Recurrent episodes of AP - 2y. O/E

Decreased BS with audible bowel sounds at

base of left lung

|

B (fall from height)

|

Co

|

4y

|

L

|

CXR: Elevated left hemidiaphragm CECT:

diaphragmatic herniation of multiple small

intestine loops

|

Lap

|

Herniated SI; diaphragm defect 10 x 6 cm

|

Reduction of DH, mesh repair of diaphragm

|

Uneventful, no recurrence at 3 y

|

|

3

|

M

|

45

|

AP - 6m; Fever 1w

|

B (motor vehicle accident)

|

Co

|

5y

|

R

|

CXR- Elevated (R) dome of diaphragm

CECT-Scan- 6x5 cm defect in R

hemidiaphragm, (R) lung collapse

|

Lap

|

Herniated gangrenous omentum with

collapsed (R) lung; diaphragm defect 7 x 6

cm

|

Reduction & excision of gangrenous

omentum, primary diaphragm repair, chest

tube

|

Uneventful, no recurrence at 5 y

|

|

4

|

M

|

55

|

Chest discomfort, abdominal distension,

& bloating- 3m

|

B (workplace accident)

|

Co

|

6y

|

L

|

CXR: Elevated and distorted (L)

hemidiaphragm. NCCT- (L) Diaphragmatic

defect with herniated air-filled splenic

flexure.

|

Lap

|

Herniated splenic flexure and omentum;

diaphragm defect 5 x 3 cm

|

Reduction of DH, mesh repair of

diaphragm.

|

Uneventful postoperative phase but lost

to follow -up .

|

|

5

|

F

|

25

|

Recurrent episodes of AP - 1y

|

B (assault )

|

Co

|

7y

|

L

|

CXR: Elevated and distorted (L)

hemidiaphragm; bowel loops in chest. CECT:

Diaphragmatic herniation of transverse

colon

|

Lap

|

Herniated transverse colon; diaphragm

defect 7 x 3 cm

|

Reduction of DH, primary repair of

diaphragm

|

Uneventful, no recurrence at 5 y

|

|

6

|

F

|

58

|

AP and bloating – 1y, Shoulder pain – 6 m

|

P (workplace accident)

|

Laparotomy, splenectomy

|

4y

|

R

|

CXR: Elevated and distorted (R)

hemidiaphragm. CECT: Herniated greater

omentum and portion of intestine, minimal

lung collapse

|

Lap

|

Herniated greater omentum and portion of

transverse colon; diaphragm defect 5 x 4

cm

|

Reduction of DH, primary repair of

diaphragm

|

Uneventful, no recurrence at 1 y

|

|

7

|

F

|

14

|

AP, Vom -

2d

|

B (fall from height)

|

Co

|

7m

|

L

|

CXR: Elevated and distorted (L)

hemidiaphragm. CECT: diaphragmatic

herniation of SI

|

Lap converted to Open

|

Herniated transverse colon; diaphragm

defect 8 x 5 cm

|

Reduction of DH, primary repair of

diaphragm

|

Uneventful, no recurrence at 7 y

|

|

AP: Abdominal pain; Vom: Vomiting; B:

Blunt; P: Penetrating; Co : Conservative ;

L : Left ; R : Right ; DH : Diaphragmatic

Hernia ; SI: Small intestine ; Lap:

Laparoscopic ; BS : Breath sounds

|

There were 5 (71.4%)

females and 2 (28.6%) males, ranging in age from

14 years to 58 years (mean 37.7 years). The

clinical presentations of the patients included

abdominal pain (n = 7; 100%), nausea/vomiting (n =

2; 28.6%), abdominal bloating (n = 2; 28.6%),

chest discomfort/breathlessness (n = 1; 14.3%),

and shoulder pain (n = 1; 14.3%). Physical

examination revealed diminished breath sounds

(n-2; 28.6%) and audible bowel sounds (n-1; 14.3%)

over the affected hemithorax. Five cases (71.4%)

had chronic symptoms ranging from 3 months to 2

years. 2 (28.6%) cases presented acutely with

symptoms for 1 and 2 days, respectively. The

mechanism of index injury was blunt in 6 (85.7%)

cases who had been managed conservatively, and 1

(14.3%) case had a history of penetrating trauma,

managed by laparotomy with splenectomy. The

interval between index injury and presentation of

PTDH ranged from 5 months to 7 years (mean 4.6

years). Hernia was left sided in 5 (71.4%) and

right sided in 2 (28.6%) cases.

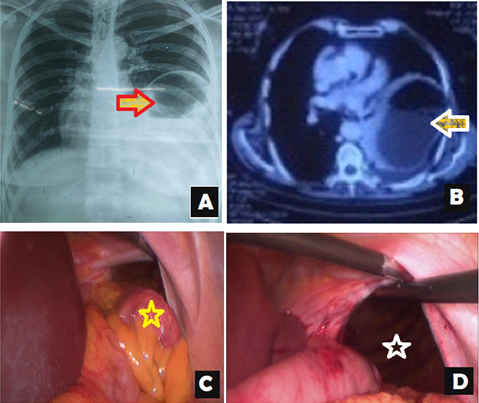

X-ray chest (with or

without plain X-ray abdomen) and CT scan

chest/abdomen were undertaken in all cases

(Figures 1A & 1B). CT scan was contrast

enhanced in 6 (85.7%) cases and non-contrast

enhanced in 1 (14.3%). These imaging modalities

revealed features suggestive of herniation of

viscera/bowel loops into the thorax. Once the

diagnosis of PTDH was confirmed, all the patients

underwent surgical operation, which entailed

reduction of hernia, repair of diaphragmatic

defect primarily with non-absorbable sutures (n =

5; 71.4%) or with mesh (n = 2; 28.6%), excision of

gangrenous omentum (n = 1; 14.3%), and tube

thoracostomy (n = 2; %). All the cases went

through an uneventful postoperative phase, and the

only postoperative complication was superficial

surgical site infection in 1 (14.3%) case. The

approach was laparoscopic in 6 (85.7%) cases, and

in 1 (14.3%) case, due to technical difficulties,

conversion to an open approach was undertaken. One

case was lost to follow-up, and there was no

recurrence in the remaining six cases at follow-up

ranging from 1 year to 7 years (3.7 years) as

determined by physical examination and imaging (

Figure 2).

|

| Figure

1: (A) CXR Chest: Raised left diaphragm,

air fluid levels projecting into lower

half of left hemithorax & left

lower lung atelectasis (red arrow). (B)

Contrast enhanced CT scan Chest:

Intrathoracic herniation of hollow viscera

(white arrow) (C) Herniated splenic

flexure of colon (yellow star). (D)

Diaphragmatic defect after reduction of

herniated contents (white star).

|

|

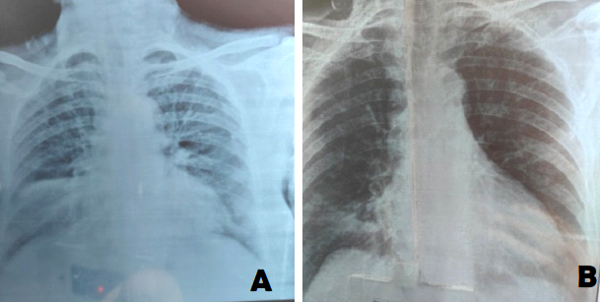

| Figure

2: Posttraumatic right diaphragmatic

hernia A: Preoperative Chest Xray B :

Chest Xray at one year follow up after

surgical operation. |

Discussion

Traumatic

diaphragmatic injury (TDI) is a rare condition

that occurs in approximately 0.5% to 5% of

abdominal trauma cases, with a ratio of 2:1 for

penetrating to blunt trauma [6]. They occur mostly

in the areas of potential weakness along

embryological points of fusion by a sudden

increase in the pleuroperitoneal pressure gradient

in thoracoabdominal trauma and result in the entry

of an abdominal viscera into the pleural cavity

[1, 7].

Historically,

Sennertus described it for the first time in 1541

when he performed an autopsy on a patient who had

died eight months after being shot and found

strangulation of the colon that had herniated

through the diaphragmatic defect [8]. Ambroise

Pare later documented PTDH in an artillery

commander in 1579, and Riolfi made the first

successful repair in 1886 [9]. The delay in

presentation can be explained because of the

pattern of emergence as below:

i. After being

devitalized due to trauma, the diaphragmatic

muscle becomes inflamed and heals by developing a

weak scar that eventually breaks down, resulting

in a defect that progressively extends in size

through radial pulling during breathing. [10].

ii. Sometimes a

defect is produced at the time of injury, but

because there hasn't been a herniation of

intra-abdominal viscera into the chest cavity, the

symptoms don't show up right away, or they get

masked up by more serious, potentially fatal

injuries [11].

The symptoms with

which the patients presented in this series

included abdominal pain (n = 7; 100%),

nausea/vomiting (n = 2; 28.6%), abdominal bloating

(n = 2; 28.6%), chest discomfort/breathlessness (n

= 1; 14.3%), and shoulder pain (n = 1; 14.3%).

None of the cases reported with hemodynamic

instability or respiratory compromise, though

cases are reported in literature where missed

hernias had manifested many months or even years

later as complications such as intestinal

obstruction, perforation, or ischemia with

morbidity and mortality rates as high as 30% and

10%, respectively [12-13]. Acute tension

viscerothorax is a manifestation where herniated

viscera into the thoracic cavity produces

hemodynamic compromise but without perforation

[14-15]. Tension faecopneumothorax (TFP) is a rare

and potentially lethal presentation of PTDHs. It

is a condition where herniated gut perforates,

releasing gas and feces-contaminated fluids into

the pleural cavity, creating an intrapleural

pressure that exceeds the atmospheric pressure,

thereby leading to adverse effects, which include

mediastinal shift, kinking of the great vessels,

reduced venous return, and cardiovascular collapse

[16-18].

The interval between

the initial trauma and the clinical presentation

with PTDH ranged from 5 months to 7 years (mean

4.6 years) in this series. When a patient presents

years or decades later, it may be challenging to

diagnose them because they may have forgotten the

episode of trauma, particularly if managed

conservatively, or else the healthcare provider

may not have enough awareness to connect the acute

symptoms to the index injury of the past [16].

Singh et al. [19] and Faul [20] have reported

cases of PTDH that presented 50 years and 40

years, respectively, after the traumatic event.

Hariharan et al. [21] reported a 65-year-old male

with splenic herniation into the left hemithorax,

causing fundal varices leading to hematemesis and

melena 28 years after the penetrating injury.

Popovic et al. [22] have presented a case where

symptoms due to PTDH appeared 26 years after the

index injury. The symptoms (epigastric pain,

meteorism, nausea, and vomiting) were interpreted

as acute alcoholic gastritis. The condition of the

patient, however, deteriorated, and on evaluation,

the diagnosis of gastrothorax was made.

In this series, PTDH

was left sided in 5 (71.4%) and right sided in 2

(28.6%) cases. This proportion concurs with the

data in the literature that shows the predominance

of hernias on the left side and is attributed to

the protective nature of the liver on the right,

the increased strength of the right part of the

diaphragm, and the weakness of the left

hemidiaphragm at embryonic points of fusion

[23-24]. The location of hernia influences the

nature of clinical features. Left-sided hernias

tend to present with obstructive gastrointestinal

symptoms, recurrent thoracoabdominal pain,

dyspnea, postprandial fullness, and vomiting [24].

Right-sided hernia is commonly limited to

respiratory difficulties, and the liver tends to

hinder the further visceral herniation due to its

bulk [25].

X-ray chest and CT

scan were the major imaging modalities utilized in

all the patients in this series. Imaging has a

significant role in the management of PTDH by

revealing features including elevation of the

hemidiaphragm, radiopacities in the hemithorax,

and displacement of the mediastinum towards the

contralateral side [8, 25]. Successful diagnosis

requires a high index of suspicion, but if

visceral herniation has occurred, diagnosis can be

made from the chest radiograph in 90% of the

patients [26-27].

In this series, the

approach adopted for surgical management was

laparoscopic in 6 (85.7%) cases, and in 1 (14.3%)

case, due to technical difficulties, conversion to

an open approach was undertaken. In literature,

different approaches have been reported, including

laparotomy, thoracotomy, combined laparotomy and

thoracotomy, laparoscopy, and video-assisted

thoracic surgery, depending on the type of injury

(acute or chronic), the laterality of the injury,

the surgeon's experience, and the availability of

equipment [8]. The literature recommends the use

of nonabsorbable suture material and that the

running or interrupted sutures can be used to

repair diaphragmatic abnormalities with comparable

efficacy [28]. The laparoscopic approach has been

found to be a safe treatment by several authors

due to its minimally invasive nature.

Conclusion

Post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias with delayed

presentation are rarely encountered and can be

challenging for surgeons. A high index of

suspicion is required for diagnosis in patients

who have a past history of thoracoabdominal

trauma. Wrong diagnosis and delay in management

can lead to morbidity and mortality .The patients

discharged after thoracoabdominal trauma need

radiographical follow-ups to detect diaphragmatic

hernias at an earlier stage. Management is

surgical, and laparoscopic approach is successful

in most situations, though the approach depends

upon the patient characteristics, skill of the

surgeons, and the availability of equipment.

Acknowledgements

The patients' consent to the use of their photos

for scholarly purposes is acknowledged by the

authors. This study does not have any financial

sources, and there are no conflicts of interest.

The article was prepared with input from each

author.

References

- Lu J, Wang B, Che X, Li X, Qiu G, He S, Fan L.

Delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: A

case-series report and literature review. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2016 Aug;95(32):e4362. doi:

10.1097/MD.0000000000004362.

- Al-Saqqa R, Sabouni R, Jarad L, Abbas N. A

delayed post-operative diaphragmatic hernia with

hemothorax due to a strangulated stomach. J

Surg Case Rep. 2020 Dec

28;2020(12):rjaa515. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa515.

- Yusufi MA, Uneeb M, Nazir I, Rashid F.

Laparoscopic Repair of Blunt Traumatic

Diaphragmatic Hernia. Cureus. 2023 Sep

26;15(9):e46017. doi: 10.7759/cureus.46017.

- Morgan BS, Watcyn-Jones T, Garner JP.

Traumatic diaphragmatic injury. J R Army Med

Corps. 2010 Sep;156(3):139-44. doi:

10.1136/jramc-156-03-02.

- Carter BN, Giuseffi J, Felson B. Traumatic

diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Roentgenol Radium

Ther. 1951 Jan;65(1):56-72. PMID:

14799666.

- Reitano E, Cioffi SPB, Airoldi C, Chiara O, La

Greca G, Cimbanassi S. Current trends in the

diagnosis and management of traumatic

diaphragmatic injuries: A systematic review and

a diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of blunt

trauma. Injury. 2022;53(11):3586-3595.

doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2022.07.002

- El Bakouri A, El Karouachi A, Bouali M, El

Hattabi K, Bensardi FZ, Fadil A. Post-traumatic

diaphragmatic rupture with pericardial

denudation: A case report. Int J Surg Case

Rep. 2021; 83:105970.

doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.105970

- Okyere I, Mensah S, Singh S, Okyere P, Kyei I,

Brenu SG. Surgical management of traumatic

diaphragmatic rupture: ten-year experience in a

teaching hospital in Ghana. Kardiochir

Torakochirurgia Pol. 2022;19(1):28-35.

doi:10.5114/kitp.2022.114552

- Schwindt WD, Gale JW. Late recognition and

treatment of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. Arch

Surg. 1967; 94(3):330-334.

doi:10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330090024006

- Yucel M, Bas G, Kulalı F, et al. Evaluation of

diaphragm in penetrating left thoracoabdominal

stab injuries: The role of multislice computed

tomography. Injury.

2015;46(9):1734-1737.

doi:10.1016/j.injury.2015.06.022

- Vermillion JM, Wilson EB, Smith RW. Traumatic

diaphragmatic hernia presenting as a tension

fecopneumothorax. Hernia.

2001;5(3):158-160. doi:10.1007/s100290100022

- Shaban Y, Elkbuli A, McKenney M, Boneva D.

Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with

transthoracic organ herniation: a case report

and review of literature. Am J Case Rep.

2020;21: e919442. doi:10.12659/AJCR.919442

- Tessely H, Journé S, Therasse A, Hossey D,

Lemaitre J. A case of colon necrosis resulting

from a delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. J

Surg Case Rep. 2020 Jun

17;2020(6):rjaa101. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa101.

- Ahn S, Kim W, Sohn CH, Seo DW. Tension

viscerothorax after blunt abdominal trauma: a

case report and review of the literature. J

Emerg Med. 2012;43(6): e451-e453. doi:

10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.084

- Ekim H, Tuncer M, Ozbay B. Tension

viscerothorax due to traumatic diaphragmatic

rupture. Annals of Saudi Medicine,

2008;28(3), 207–208. doi:

10.5144/0256-4947.2008.207.

- Chern TY, Kwok A, Putnis S. A case of tension

faecopneumothorax after delayed diagnosis of

traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Case

Rep. 2018;4(1):37. doi:

10.1186/s40792-018-0447-y.

- Ramdass MJ, Kamal S, Paice A, Andrews B.

Traumatic diaphragmatic herniation presenting as

a delayed tension faecopneumothorax. Emerg

Med J. 2006;23(10): e54.

doi:10.1136/emj.2006.039438

- Kafih M, Boufettal R. A late post-traumatic

diaphragmatic hernia revealed by a tension

fecopneumothorax (a case report). Rev Pneumol

Clin. 2009;65(1):23-6. doi:

10.1016/j.pneumo.2008.10.004.

- Singh S, Kalan MM, Moreyra CE, Buckman RF Jr.

Diaphragmatic rupture presenting 50 years after

the traumatic event. J Trauma. 2000

Jul;49(1):156-9. doi:

10.1097/00005373-200007000-00025.

- Faul JL. Diaphragmatic rupture presenting

forty years after injury. Injury. 1998

Jul;29(6):479-80. doi:

10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00082-5.

- Hariharan D, Singhal R, Kinra S, Chilton A.

Post traumatic intra thoracic spleen presenting

with upper GI bleed!--a case report. BMC

Gastroenterol. 2006 Nov 28;6:38. doi:

10.1186/1471-230X-6-38.

- Popovic T, Nikolic S, Radovanovic B, Jovanovic

T. Missed Diaphragmatic Rupture and Progressive

Hepatothorax, 26 Years after Blunt Injury. Eur

J Trauma 2004; 30:43–46.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-004-1327-7

- da Costa KG, da Silva RTS, de Melo MS, Pereira

JTS, Rodriguez JER, de Souza RCA, de Oliveira

Medeiros IA. Delayed diaphragmatic hernia after

open trauma with unusual content: Case report. Int

J Surg Case Rep. 2019;64:50-53.

doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.08.030

- Christie DB, Chapman J, Wynne JL, Ashley DW.

Delayed right-sided diaphragmatic rupture and

chronic herniation of unusual abdominal

contents. J Am Coll Surg. 2007

Jan;204(1):176. doi:

10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.05.007.

- Testini M, Girardi A, Isernia RM, De Palma A,

Catalano G, Pezzolla A. Emergency surgery due to

diaphragmatic hernia: Case series and review. World

J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:23. doi:

10.1186/s13017-017-0134-5.

- Maddox PR, Mansel RE, Butchart EG. Traumatic

rupture of the diaphragm: a difficult diagnosis.

Injury. 1991 Jul;22(4):299-302. doi:

10.1016/0020-1383(91)90010-c.

- Peer SM, Devaraddeppa PM, Buggi S. Traumatic

diaphragmatic hernia-our experience. Int J

Surg. 2009 Dec;7(6):547-9. doi:

10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.003.

- Necke K, Heeren N, Mongelli F, FitzGerald M,

Fornaro J, Minervini F, Metzger J, Gass J M.

Faecopneumothorax caused by perforated

diaphragmatic hernia. Case Rep Surg.

2020; 2020:8860336. doi:10.1155/2020/8860336.

|